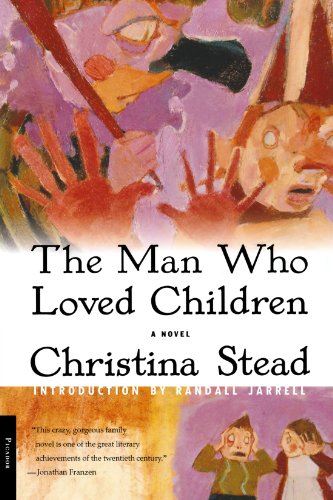

THE MAN WHO LOVED CHILDREN was published seventy-five years ago, and it remains one of the most aggressive, extraordinary, preposterously sustained, and imaginative novels ever written, even though the characters and much of the situation were based on people their author, Christina Stead, knew intimately. It seems that Stead created her family of Pollits out of sheer writerly wizardry, so grotesque and alive are they—Henny, the vicious, hysterical mother; Sam, the narcissistic, pontificating father; Louie, the dumpy, dreary issue of an earlier marriage and the brilliant, suffering, sullen pivot on which the novel turns; and the little Pollits, a ravishing, filthy, feral tribe of six.

Stead was Australian but traveled extensively with her husband, a Marxist economist nicely named William Blake. She wrote her opus, which is set on the outskirts of Washington, DC, in New York City, in eighteen months. Stead described herself as a psychological writer for whom personality was a “passion,” and felt that most writings, even well-known ones, lacked truth. She had “an irresistible urge to paint true pictures of society as I have seen it.” But her painterly eye was a phantasmagoric one, avid and extreme. The reader not only sees the Pollits but smells their reek, as he falls under the fearful enchantments of their stories, dreams, brawls, and private patter—a mixture of buffoonery, sophisticated spoonerisms, and babbling baby talk.

Stead felt she understood men better than women, having been introduced early to the friends and colleagues of her restless, erudite naturalist father, but also “wished to understand men and women equally.” The Man Who Loved Children is a portrait of the female artist as a young ugly duckling. Stead is Louie, whose “brain boiled by day and night.” She seeks to “invent an extensive language to express every shade of her ideas.” Stead’s father, David, is Sam, self-bedazzled, curious, confident, absurd. He did indeed love children, but only little ones. Adolescence—when they would become sexual creatures and harbor thoughts not his own—frankly troubled him. As for the slatternly and desperate Henny, she could exclaim: “A mother! What are we worth really? They all grow up whether you look after them or not.”

Stead was a magnificently natural writer—craft did not inhibit her, satire did not interest her, form was a cage from which to escape. Still, Elizabeth Hardwick claimed that The Man Who Loved Children was “faithfully plotted . . . realistically set, its intention and drive . . . openly and fully revealed,” and she was quite correct.

In 1965, Randall Jarrell wrote an extensive and pretty much unsurpassable introduction to the reissue of the novel. He titled it “An Unread Book,” lamenting that this masterwork was so little cherished in our shortsighted world, even daring to proclaim: “If all mankind had been reared in orphan asylums for a thousand years, it could learn to have families again by reading The Man Who Loved Children.”

We can only pray that this would not be the case. The Pollits—this messy bewildered poverty-racked family steered through life by two shrieking, quarreling, fabulously destructive gods—would be an unfortunate template for future instruction. Better, perhaps, to take our cue from the family of elephants in Barbara Gowdy’s strange, superb, and likewise neglected novel The White Bone, for they are intelligent, loyal, and caring. But to our shame, the elephants will be exterminated by us long before we, the human family, exit, howling, hungering and deluded to the end, from this world’s wondrous stage.

Joy Williams’s The Visiting Privilege: New and Collected Stories will be published this fall by Knopf.