TOUSSAINT, ONE OF TWO SETTINGS for Nalo Hopkinson’s novel Midnight Robber (2000), is a high-tech planet settled and controlled by Afro-Caribbean emigrants from Earth who wanted to make a new world in their own image, “free from downpression and botheration.” Toussaint looks like fun, too, though it’s only going to feel like home if you are West Indian (that’s part of what its founders meant it to do): It has carnival season, and Junkanoo parade, and mangoes, and African-derived names for its technology (“eshu” for cybertracers, for example). Most people on Toussaint accept the benevolence, along with the surveillance, of the supercomputer called Granny Nanny—as in grand nanotech, as in nanny state, as in Anansi the spider, a supermother that spins a worldwide web. The planet could be a delight, a continual family reunion charged with cybernetic gemütlichkeit.

It could be, but it’s not that way for Tan-Tan, because her own family has been falling apart. Her father, Antonio, the local mayor, has just caught her mother, Ione, in bed with another man. Antonio challenges that other man to a duel (legal on Toussaint), then kills him in public, with a poisoned blade (definitely illegal); he flees Toussaint’s police, kidnaps Tan-Tan, and takes her to a strange new planet “where nobody could tell we what to do.” That planet is New Half-wayTree, a place of exile for Toussaint’s criminals, who have built up their own villages and farms—some of them cruel and half civilized, some with real slavery.

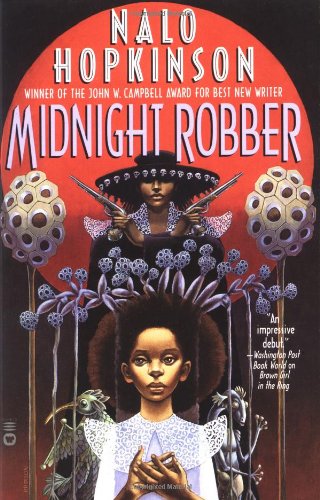

Hopkinson’s second novel is a far-future adventure, a neat example of how to build alien worlds, and an exemplary work of Afrofuturism, narrated partly in West Indian patois. It becomes a harsh allegory of colonial contact when humans encounter a species of intelligent aliens known as “douen.”

Midnight Robber is also a book about childhood, motherhood, and family; about patriarchy, rape, pregnancy, and reproduction; about how we find, and reimagine, a family if the one we get does not work out. It does not yield the by now familiar plot in which a teen flees an abusive traditional household for a scrappy community of cooler peers. Like the worlds she creates, Hopkinson’s story is too conceptually elaborate to condense, but I will reveal one key plot point: Tan-Tan gets pregnant. Her escape from her home planet, her search for a better community, is also a search for the right way to be a teen mom and a search for a story about growing up that is not just a story of independence, not just a story of learning to live on your own.

Midnight Robber becomes an unlikely feminist, or womanist, guide to the use of extended and traditional families; the scared, resourceful, sassy teen protagonist discovers that familial loyalties, when they work properly, are her strongest ways to resist a patriarchal society founded on brute force. Patriarchy means rule by the fathers, for the fathers—that’s what Antonio wants, and what Tan-Tan escapes; her trek across New Half-way Tree—and our tour of the twinned planets that she has known—allows us to ask, along with her, how else we can organize a society and a household or a family, so that the girls and women, as well as the boys (Tan-Tan meets a neat boy), can work together to raise each other, and pass on a distinctive culture to a future in which nobody has to make it alone.

Stephen Burt is a professor of English at Harvard and the author of several works of literary criticism and poetry, including Belmont (Graywolf, 2013) and All-Season Stephanie (Rain Taxi, 2015).