In Charles R. Rushton’s 1991 black-and-white portrait, Agnes Martin (1912–2004) sits in a wooden rocking chair in the left third of the frame, beside the white cement wall of her New Mexico studio. One of her canonical six-by-six-feet canvases hangs low to the ground next to her, its horizontal pencil-edge bands running out of the picture to the right. She’s dressed like a plainclothes nun, in comfortable white sneakers, flannel pants, and a collared shirt under a dark cardigan buttoned to the neck. Her hands are seton each armrest with a square assurance that recalls Gertrude Stein, and the photo’s spare formality is reminiscent of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s 1871 portrait of his mother, Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1. These elements suggest theperfect stillness associated with Martin’s profoundly absorbing minimalist abstractions and her devotion to painting the uniform square through an exacting process over half a century. Yet there are two subtle disruptions to the calm, details sometimes cropped out of the picture’s bottom edge. That rocker! Those sneakers!

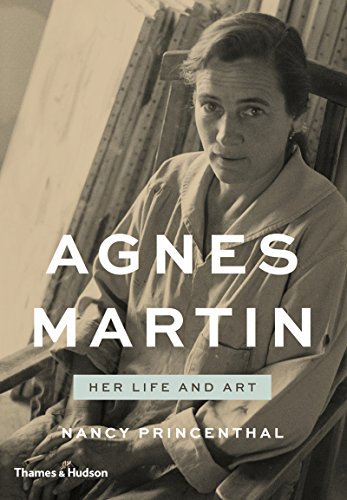

Is it our assumptions about Martin that create her apparent contradictions, or is it the other way around? She has endured the critical paring knife inflicted on all “pure” painters who insist the real world is far removed from their work: We love the smooth, monochrome skin but we also want to get to the juicy pulp, the bitter seeds. Nancy Princenthal’s brisk biography Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art neatly lays out the incongruities: the Martin who insisted that nothing was more important to her than the ocean yet lived most of her life in the desert; Martin the ascetic guru, subsisting through the winter on hard cheese and walnuts and homegrown, preserved tomatoes, yet also the margarita- and steak-loving life of the party who, meeting the president and first lady to receive the National Medal of Arts award in 1998, “appreciated [Hillary Clinton’s] personality”; Martin the disciplined practitioner who woke up early every morning to paint, and who admitted, “I don’t get up in the morning until I know exactly what I’m going to do. Sometimes, I stay in bed until about three [in] the afternoon, without any breakfast.” She even had an unlikely passion for fast cars: At the book’s start, we have Rosamund Bernier’s image of Martin “flying” down the dirt road in New Mexico at the wheel of a “white BMW sedan,” and near the end, in the last year of her life, we find Martin in a “spotless” E320 Mercedes. Her art dealer, Arne Glimcher, in turn, discusses her “reckless” habits on the road (she didn’t believe in Stop signs), and recounts going eighty miles per hour with Martin in the passenger seat asking him, “Why are you driving so slow?” What’s clear here is that, despite her apparent serenity, Martin was driven.

Nowhere in Martin’s life is the tension between stillness and its opposite thrown into sharper relief than in her schizophrenia, a subject we learn much more about through Princenthal’s nuanced documentation. The artist’s acute catatonic episodes were short-lived but traumatic ruptures in her artmaking; she experienced paranoia and aural hallucinations—what she called her “voices”—throughout her life. Her illness may have been the context for many of her contradictions, and even her deliberate, laconic parables of art. But Princenthal dismisses the familiar myth of the mad hermit, working without recognition or conscious agency. We realize, instead, that Martin has never really left our consciousness. Particularly not in New York in the past decade, since Catherine de Zegher’s 2005 exhibition at the Drawing Center brought her into the mystical company of Hilma af Klint and Emma Kunz, and since the Dia Art Foundation made a sustained commitment to Martin, one of the only women artists permanently on view at Dia:Beacon, in a triumphant suite of galleries. Lynne Cooke curated an important group of focused exhibitions there from 2005 to 2009 and edited a related anthology of essays and artists’ talks. In 2013, Jutta Koether staged a feverish performance lecture on Martin at Dia Center for the Arts in New York City.

This summer brings more reminders of Martin’s extraordinary practice, which stretches in measured seriality from her first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons gallery in 1958 until her death in 2004. There is the Tate Modern’s retrospective (the catalogue has a few revelations, including a 1966 portrait of Martin by Diane Arbus and a brief survey of Martin’s reception in Europe, where just twenty of her large-format paintings exist in public collections). Phaidon has reprinted Glimcher’s lush 2012 homage to Martin and their thirty-year dealer-artist relationship, Agnes Martin: Paintings, Writings, Remembrances, complete with facsimiles of her handwritten notes, Polaroids from Glimcher’s studio visits in New Mexico, and impeccable reproductions of her drawings and paintings on oversize square pages. And one of Martin’s gnomic parables of love and beauty has just been published as an artist’s book, Religion of Love, edited by her good friend Richard Tuttle, who also provided illustrations. Along with Princenthal’s biography, these are only the latest reincarnations of an artist who claimed that she’d “been on the planet many times before, as men as well as women, and also as children.”

This is one more contradiction, between separateness and communality: If Martin’s Delphic concision in her paintings suggests a world apart, she nonetheless insisted that she had already returned many times over to be a part of this one—of America, specifically, the country she settled in and quixotically wandered through, claiming to have visited every contiguous state. It’s a place where she worked as a hard laborer, teacher, and artist; where she lived in poverty and became very rich. In fact, hers are the great, stark contradictions of America itself, a landscape defined by ocean and desert, urban drive and pastoral stillness, capitalist appetite and Calvinist restraint.

Martin was an incomparable editor of her own work. Her creative process was not so much economical as merciless: Princenthal quotes Martin’s explanation that early in her career “I just painted and threw them away and painted and threw them away until I got at the place where I felt I was doing what I felt I should.” Glimcher also dispels the myth that Martin worked slowly and minimally. In fact, “she painted almost daily,” when she wasn’t suffering from her illness; the compactness of her oeuvre is due to the fact that “she destroyed most of the works she produced,” shredding them with a mat knife.

She was also an incomparable narrator of her own life, despite her wariness of biography’s role in art; but here too she was constantly revising. Princenthal’s book’s most vivid (and, at times, parafictional) passages quote the artist’s own words, including this astonishing recollection of her birth: “I can remember the minute I was born. I thought I was a small figure with a little sword and I was very happy. I thought I would cut my way through life victory after victory. Then, they carried me into my mother and half my victories fell to the ground.”

Martin was born into a family of homesteaders in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan in 1912 (she became a US citizen in 1950), and some of her early recollections “seem borrowed from Little House on the Prairie,” Princenthal astutely observes. As a child, she collected postcards of famous paintings, which she copied—the first glimpse we have of her calling. She worked as a driver for a young John Huston and as a cook in a lumberyard, where “she remembered baking twenty-five pies each morning.” Obtaining a teacher’s certificate in Washington state, Martin ventured to New York in 1941 and enrolled at Teachers College, where the majority of her classes were in studio art. She left shortly after, working a number of jobs in various states before arriving in New Mexico in 1946, where she met Georgia O’Keeffe and Betty Parsons. Martin’s account of spending time in the company of the grande dame O’Keeffe anticipates how others would later describe visiting Martin on her mesa: “Georgia was . . . very intense and exciting to be with, but she drained me. When I left the room for a few minutes, I just had to lie down, right then and there.” In the ’50s, Martin lived in near povertyin Taos, in a place without indoor plumbing but with a great studio, where she began painting in earnest.

At the age of forty-five, still a year from her first New York exhibition, Martin moved back to the city at the urging of Parsons, living with her briefly before moving into an illegal studio in Coenties Slip near the Fulton Fish Market on the East River. Her neighbors were Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, Lenore Tawney, Ann Wilson, and Jack Youngerman. She occupied a huge loft whose spare furnishings included a bathtub in the bedroom and a rocking chair; she and Kelly had breakfast together every day. In 1966, she participated in the Robert Smithson–curated exhibition “10” at Virginia Dwan Gallery, along with her fellow Abstract Expressionist–generation colleague Ad Reinhardt and a younger crew of emerging Minimalist artists; while “flattered” to be a part of the show, she felt detached from their scene, explaining, “my paintings are not cool.”

Martin abruptly left New York in the summer of 1967, after a series of traumatic events that included the untimely death of Reinhardt, the loss of her loft, and a schizophrenic episode that led to her being committed to Bellevue’s mental hospital, where she underwent electroconvulsive therapy.

Again following a current of the American experience, Martin moved from the ’60s sociability of the New York art scene to the desert-scale wilderness found in ’70s Land art.(One fascinating, if underexplored, aside in the biography concerns Martin’s interest in Earthworks and her unrealized plans for a Zen garden.) Princenthal makes clear that Martin “left” artmaking for just four and a half years, rather than the oft-cited and more biblically symbolic figure of seven. Regardless, it was an intense period of withdrawal: “I am staying unsettled and trying not to talk for three years,” Martin wrote of her plan. She drifted through the Pacific Northwest, Canada, and the American Southwest in a white pickup truck, sleeping in a camper. (She subsequently described these eighteen months as “a camping trip.”) And she continued editing the story of her wanderings years later: “I thought I would withdraw and see how enlightening it would be. But I found out that it’s not enlightening. I think that what you’re supposed to do is stay in the midst of life.”

She ended up in the remote town of Cuba, New Mexico, in 1968, where “she secured a lifetime lease, at ten dollars a month, for fifty acres.” (Her voices had told her not to buy property.) She was fifty-six and, Princenthal writes, “had no telephone and no electricity; rainwater was collected for drinking.” She began building a studio out of adobe and logs, hefting huge stones. As she embarked on this project, one akin to those of the first settlers of the American West, her reputation at the center of an intellectual engagement with postwar abstraction reached its acme back East. Her “return” to art was signaled by a major survey exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in January 1973; one of her paintings graced the April cover of Artforum that same year, and, among several public talks, she delivered a four-thousand-word lecture from memory at the Pasadena Art Museum. By 1975, she was showing with Glimcher at Pace Gallery. A few years later, her lease broken by the landowner, she moved south to Galisteo, a town that would grow to host a thriving arts community. She remained in New Mexico, painting and tearing up the roads, until her death at the age of ninety-two. Her final works return to some of her earliest motifs—basic geometries and gray bands, washes of dusty and overcast color, and the ever-present straight-edge pencil line—suggesting an unwavering perception among wavering visions.

Princenthal has done a heroic service in scouring the glut of sources—reviews, documentaries, interviews, previous publications—for the brightest quotations and strangest anomalies. She strings these together into an engaging narrative interspersed with formal descriptions and bibliographic exegeses of Martin’s paintings, drawings, writings, and single film. Understandably, this leads to some repetition—quotations and ideas sometimes reappear without being developed. You don’t have to know anything about Martin to enjoy this book, though, and I mean that as a compliment. Princenthal’s tone is assured and reassuring; I trusted her, even when I wished she had taken a few more risks in her analysis. (She is kind to everyone who has written about Martin, and qualifies her own conclusions as speculative.) The book generally moves chronologically—the account of Martin’s childhood is riveting, and art geeks will love the anecdotes of ’60s New York—but certain topics continually interrupt the flow (as they do in life itself), most notably Martin’s schizophrenia.

Princenthal’s book offers the frankest discussion to date of the artist’s diagnosis. It examines the shifting perception and treatment of mental illness in the US during Martin’s lifetime, and also the rarity of her condition, which afflicts only 1 percent of the population. In Princenthal’s telling, schizophrenia is central to Martin’s story, even if she sometimes managed to ignore it. But we should not pathologize the painting by directly linking its formal qualities to her illness. She didn’t work when she was suffering from her voices—she would “sit in her studio or at home in her rocking chair and wait,” as one friend remembers—which makes the extreme editing of her paintings that much more remarkable. We do see schizophrenia’s effect in her working process: Her illness forced her to seek out solitude.And it entailed a constant negotiation between what Princenthal calls “vision and thought”: timeless perceptive understanding versus time-bound agitations of the mind. As Jonathan Katz writes, “For Martin, art is an act of willful forgetting, of turning the mind away from thought and back toward perception.” Perception held an interpretive power, unlike her hallucinations, to judge and shape a picture’s experience.

Princenthal is more cautious on the subject of sexuality. “Martin is said to have had romantic relationships with two women artists: Chryssa . . . and Lenore Tawney,” she hedges. She lets others make explicit proclamations. Jack Tilton is quoted as saying that “everyone” knew Parsons and Martin were lovers in the ’50s. (Still, as Princenthal points out, Martin’s name is not mentioned once in Parsons’s interview for the Archives of American Art.) And at a 2012 symposium, Martin’s lifelong friend Kristina Wilson said that she and Martin were also lovers in the ’50s. Martin denied being a lesbian, though. She was an isolationist, refusing to be attached to anyone or any cause; sometimes she even refused a signifying pronoun altogether, referring to individual women with the distant “they.”

Martin’s refusals can best be cast in terms of what they repressed or elided: appetite. Her incredible self-discipline, bred from a strong Calvinist streak, extends beyond intimacy. She was a consummate baker, but she put herself on extreme diets when working so as not to have any distraction. “Sometimes I’ll eat one thing, like bananas, and anytime I get hungry, I say, ‘Agnes, have another banana’ and that’s it, I won’t eat any more,” she told Glimcher. On another visit to her studio, he noted that she was “only eating Knox gelatin mixed with orange juice and bananas.” She defended her parsimoniousness in a lecture at Yale University in April 1976, in which she explained, “In the studio an artist must have no interruptions from himself or anyone else. Interruptions are disasters.” Lest we mistake this for artistic entitlement, we should remember that interruptions, for her, included uninvited voices—”disasters” without exaggeration. She also spoke of appetite as a universal experience, another common ground pushing against her separatism: “There is a great hunger and thirst in all of us for the truth whether we are aware of it or not,” she stated. “To think oneself unique is the height of ignorance. Appetite is of course positive but sometimes in moments of weakness we have an immense yearning to escape.” In place of appetite, Martin celebrated devotion—or drive—the feeling that makes artwork and “literally carries us through life, past all distractions and pitfalls to a perfect awareness of life, to measureless happiness and perfection.”

An unexpected and alluring source of Martin’s sense of devotion goes undeveloped in Princenthal’s book. As an undergraduate researching the artist, Princenthal wrote Martin a letter. Martin sent a long letter back, encouraging her, among other things, to read Walt Whitman. This was not the reply Princenthal had hoped for; like Martin’s statements on art, it signaled a redirection (a misdirection, even) into the poetic ether. But Whitman, America’s champion of sensual, democratic fraternity and self-celebration—a poet who is above all about appetite—was an intriguing choice.

Certainly, Martin’s reference to Whitman has to do with nature, which, paradoxically, was the very thing that let her ignore the outside world and paint; one of her works, as if in acknowledgment, is titled Gratitude. Even in the city, Martin sought out some form of nature to clear her mind, once telling a reporter, “The best thing to do when you stop painting . . . is cross the Brooklyn Bridge.” While most of her works are untitled, a number of early abstract canvases have names evoking landscapes and their objects (she claimed friends helped title them): The Peach, Desert Rain, Buds, Wheat, A Grey Stone, The Tree, Leaves. This, in contrast to the surprising Hallmark lilt of some of her final titles, including Lovely Life, Happiness, Little Children Loving Love, and Affection. Seen through a Whitmanesque lens, the arc of her titles, from nature to absence to sentiment, is not so much contradictory as revealing ofan enduring drive for universal communion within the creative self, a continual push and pull between abstraction and metaphor. This tension is part of modernism, but its optimism makes it particularly American.

Maybe, too, Martin admired Whitman’s open embrace of the sublime, despite scolding him in a 1981 text for taking too much personal credit for his expressive perception. After all, ecstasy and agony coexist in her descriptions of her art, despite its order. “All my paintings are about joyful experiences.” And: “Only joyful discoveries count. If you are not making them you are not moving.” We know a little better now the extreme difficulties Martin withstood to reach that joy, how it had to be measured from the other side: “A sense of disappointment and defeat is the essential state of mind for creative work,” she lectured in 1973. “There’s a lot of failure. I’ve said that the ability to recognize failure is the most important talent of an artist.” Such perceptions were her constraint and her freedom—that double-edged sword she wielded her whole life.

Prudence Peiffer is an art historian and a senior editor of Artforum.