Twenty-five years ago, in a review of Abdelrahman Munif’s ambitious “petronovels,” Amitav Ghosh asked why fiction had proved so mute when it came to the momentous story of Middle Eastern oil. Other globally disruptive enterprises—Ghosh’s preferred example is the spice trade—didn’t lack for a robust literary response, like the epic Portuguese poetry that sprang up alongside the discovery of a sea route to India. But the story of fossil fuels had not found its place in serious fiction, despite its tantalizing offerings to would-be chroniclers—its “Livingstonian beginnings” in the Arabian sands, and its “city-states where virtually everyone is a ‘foreigner’; admixtures of peoples and cultures on a scale never before envisaged; vicious systems of helotry juxtaposed with unparalleled wealth; deserts transformed by technology, and military devastation on an apocalyptic scale.” Ghosh asserted that only a novelist eager to rise to the challenge of a “bafflingly multilingual” territory, a landscape featuring an intrinsically displaced, inordinately international atmosphere, could overcome the difficulties of writing about such a disorienting and cacophonous moment.

Twenty-five years later, Ghosh’s essay reads like a personal memo tacked to the wall of his writing studio as he composed his gargantuan “Ibis” trilogy, dedicated to another world-changing industry—the opium trade that linked Britain, India, and China and led to the war that transformed the economies and politics of all three countries, leaving an indelible mark on the map for the next century. The First Opium War (1839–42) forced open Chinese ports and markets, bled the Chinese economy, and allowed Britain to add Hong Kong to its colonial possessions. (To later nationalists, it would become known as year one in the “Century of Humiliation.”) And in India, the trade became so integral, accounting for nearly a fifth of its revenues, that its disruption might have led to the collapse of the colonial economy. The poppy changed the world of the nineteenth century. “Blessed indeed are those, Reid, whom God chooses to be present at such moments in history!” a blustery opium tycoon tells an employee he is goading into the trade in Flood of Fire, the new and final volume of Ghosh’s 1,600-plus-page trilogy. “Think of Columbus, Cortez and Clive! Is there any greater or more satisfying endeavor for a young man than to expand his own fortunes while extending God’s dominion?” Ghosh has—to say the least—a less sanguine view of the nineteenth-century dope trade, which culminates in Flood of Fire in the conflagrations between China and Britain, but he is no less buoyant in exploiting the raw materials of the encounter to create complex geopolitical drama.

Plotted as assiduously and with as much advance research as a military campaign over the course of three volumes—Sea of Poppies (2008), River of Smoke (2011), and now Flood of Fire—Ghosh’s project is a forceful contribution to an often underappreciated trend in recent fiction, the reinterest in the historical novel, from Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall to Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North. He has done so by combining a historian’s affection for the archive with an anthropologist’s appreciation of the thickness of local realities and a novelist’s gift for plot, character, and language. Bafflingly multilingual? Characterized by the intrinsic displacement of peoples? These gritty actualities of mercantile and naval empires run the risk of becoming deadweights on the text, but Ghosh uses them to charge his tale. Around a set of characters who reappear from volume to volume—often with shifting identities, like the Bengali seaman Jodu, who has morphed from a green apprentice on the Ibis in the first volume to a devout Muslim in service to the Chinese in the last—Ghosh fashions a history that seems always on the move, vibrantly and restlessly progressing toward its conclusion.

Among those familiars from the first two books of the trilogy are a trio whose ambitions and worldviews are starkly at odds: Benjamin Burnham, a British ship owner, moralist, and opium trader, whose already vaunted stock is on the rise; Neel Rattan Halder, a zamindar whose fall from grace via Burnham’s machinations leads him from opulence in India to a more circumscribed and somber existence in China; and Zachary Reid, a young seaman from Baltimore of mixed racial parentage out to make his fortune. A powerful Englishman, an upper-caste Indian, and a young American with a complex background, who passes for white to nearly all but Burnham’s devout right-hand man, who takes him for black (a holy incarnation appropriate to Kali Yuga, the epoch of the apocalypse): The three form a sort of through-line in the trilogy, with each providing an angle on the colonial experience. Their stories are also deeply enmeshed. When we meet Reid in Flood of Fire, he has been hired to work for Burnham, first to restore the pleasure barge the businessman has seized from Neel, then to oversee the ship-bound transport of opium from Calcutta to Canton (along the way, he will also attend to Burnham’s Victorian cougar of a wife, a comic education in what she calls “the art of the puckrow”). Neel, by contrast, has made his way to Canton, where he works as a translator and circumspect eyewitness to the events in China following the confiscation and destruction of opium—some three million pounds’ worth—by the crusading commissioner Lin Zexu.

Each of the novels depends heavily on the theme of transportation, either in the movement of narcotic goods, indentured laborers, and speculators from India to China or in the more metaphorical flights of Neel, Reid, and the newcomers to Flood of Fire (the sepoy Kesri Singh, who leads a group of Bengali troops to battle in China; the widow Shireen Modi, who risks loss of caste when she travels east in hopes of reclaiming an opium fortune). Ghosh has an affinity for various figural triangles, and it’s fitting that a novelistic landscape that seems always in motion should revolve around the story of three ships. His fictional trio of transports reveals how mercantile interests, with a rhetoric of “free trade” and a self-justifying belief in a civilizing project, went hand-in-hand with revolutionary sea power to force a military confrontation and pry open a massive market. The ships speak, too, of how malleable those rhetorical justifications could be, as well as of the narratives of human misery hidden in their histories. The first of these ships, the Ibis, a onetime slave vessel converted to transport the newly impressed Indians of the poppy-growing region of Bihar to the plantations of Mauritius, is the stage for the climax of Sea of Poppies. In River of Smoke, the scene has shifted largely to the opium carrier The Anahita and the gamble by a Bombay merchant to unload his massive quantity of the drug in Canton in the face of the growing Chinese crackdown (a thread that will be picked up by the fate of his widow, Shireen). Now, in the final book of the trilogy, Burnham’s boat The Hind, with Shireen, Reid, and others in tow, charts its way from Calcutta to the channels upriver from Canton. The last ship is only one species in a menagerie of vessels that make up the water world of Flood of Fire, from the junks piloted by the Chinese to the “fast crabs” that swiftly ferry contraband up the shore to the menacing iron warship The Nemesis, which will quickly make the fight between the Chinese and the British a rout.

In his trio of character-like ships, Ghosh has found a pungent conceit for the themes that run through the trilogy. They embody the vicious efficiency of the opium trade and the cruel equation of technological wonder and lethal violence, but they are much more than that. Microcosms of the Indian worlds, they too are sea-bound emissaries of the British Empire and home to a motley collection of seamen hailing from across the globe, especially the lascars from ports throughout Asia. Onboard, these floating cities form a fluid soundscape where English, Bengali, Bhojpuri, and others in a range of sociolinguistic registers jostle against one another and new lingua francas—amalgams of nautical jargon and stripped-down pidgin—take root. The sea routes are after all a recipe for pidginization, with speakers of unrelated languages finding a newly born tongue to communicate across linguistic barriers. And with the mélange of languages and dialects comes an unpredictable form of social intercourse, in which identities can change or harden, caste can come undone, veils can be raised and lowered.

Ghosh takes a tremendous delight in the linguistics of colonial contact and exchange. Even casual, listlike descriptions of a scene in a Cantonese printer’s shop or at a Calcutta opium futures market feature a vivid combination of precision and obscurity. Early on in Flood of Fire, Ghosh describes a fateful message received by the sepoy Kesri from one Pagla-baba, a “mascot and mendicant” accompanying the Bengali troops.

Ka bhaiyil? What is it, Pagla-baba?

Hamaar baat sun; listen to my words, Kesri—I predict that you will receive news of your relatives today.

Bhagwaan banwale rahas! cried Kesri gratefully. God bless you! Pagla-baba’s prediction whetted Kesri’s eagerness to be back at the camp and he forgot about Gulabi. Spurring his horse ahead, he trotted past the part of the caravan that was reserved for the camp-following gentry—the Brahmin pundits, the munshi, the bazar-chaudhuri with his account books, the Kayasth dubash, who interpreted for the officers, and the baniya-modi, who was the paltan’s banker and money-monger, responsible for advancing loans to the sepoys and for arranging remittances to their families. These men were travelling in the same cart, chewing paan as they went.

There’s pleasure in coming upon these bursts of linguistic census-taking. Ghosh has an almost ethnographic curiosity about these minute worlds of subcontinental contact, drawing on a seemingly boundless list of recherché terms that he dug up while doing archival work for the trilogy (each novel carries a voluminous list of sources). Gomustas, khidmatgars, havildars, and jawans provide verbal form, in their own words or in the makeshift modes of communication between those who don’t speak the same language. Ghosh often doesn’t bother to translate his terms—he lets the essential oddness of colonial contact remain just as mystifying to the reader as it is to the characters. But he also plays the collision of languages, which can be baffling even to intimates, to humorous effect. After Zachary gets a lesson from his puckrow-partner Mrs. Burnham in “chewing on a chichky” (“It is a wonder to me . . . how quickly you have mastered the mystery of the gamahuche!”), he shrugs about a different kind of lingual competence. “I never was no word-pecker,” he protests. “How’m I to keep pace with you?” Aptly enough, she replies, “Oh fiddlesticks. . . . And you a sailor! You should be ashamed to admit to a lack of words!”

But there is a corrosive side as well to the language of contact and the cursed “lack of words.” Working for the Chinese printer Compton, who specializes in producing English-language documents, Neel—the moral center of both Flood of Fire and the trilogy as a whole—senses the emerging darkness and the coming show of British might. “Nowadays,” he writes in his diary, “Compton’s fretfulness bubbles over quite often. In the past his attitude towards translation was fairly matter-of-fact. But now it is as if language itself had become a battleground, with words serving as weapons. . . . He disputes everything, even the way the English use the word ‘China.’” In the face of gunboat diplomacy, Neel sees the futility of the ambitions of the Chinese to preserve their autonomy and the disaster that awaits those who resist. “I suppose this is much how things were in Bengal and Hindustan at the time of the European conquests, and even before. The great scholars and functionaries took little interest in the world beyond until suddenly one day it rose up and devoured them.”

Ghosh takes tremendous interest in those worlds, and Flood of Fire animates them in terrific feats of digression on subjects as varied as the sociology of sepoy recruitment, the aesthetics of Hindu wrestling matches, the mechanics of Opium War muskets, and what it means when a young seaman gives a belaying pin a shine. The thickness of facts matches the density of relations among his characters. The networks formed by their multiple connections—catalyzed by boat and by market—are intricate and complex. If plotted, they might resemble the baroque loops of a Mark Lombardi drawing or a Fed agent’s chart of a mob family’s tentacles. And like mafiosi, various characters drop out of sight for extended periods, only to wash up in an unexpected context on a different shore hundreds of pages later. But Ghosh is determined that the reader experience the epic weight of the opium industry, in its historical unfolding and in the lives of his characters. It’s a false dichotomy in the trilogy, and in Flood of Fire itself, to think of these two spheres as separate. If Ghosh began his professional career with considerable academic training—he holds a Ph.D. in anthropology—his work as a novelist never takes on a didactic cast, and his triumph here is to make it impossible for the reader to distinguish between the historical destiny of the story and the destiny of his characters. From Shireen’s discovery of a new life in China to Zachary’s transformation from a puckish, fare-thee-well sailor into a calculating businessman who seemingly makes his own fate, Ghosh’s characters bring his trilogy and its historical basis to vivid fulfillment. Even the way in which his characters overlap seems to flow organically from the vicissitudes of the opium trade and war. It is a powerful gesture to bring together ship owners, subalterns, and the most exploited of the untouchables, and to have them rub shoulders through the sea route, the marketplace, and the battlefield. Like the global reach of Middle Eastern fossil fuels, the trade in opium affected everyone. Even in the big picture of history, it’s a pretty small world.

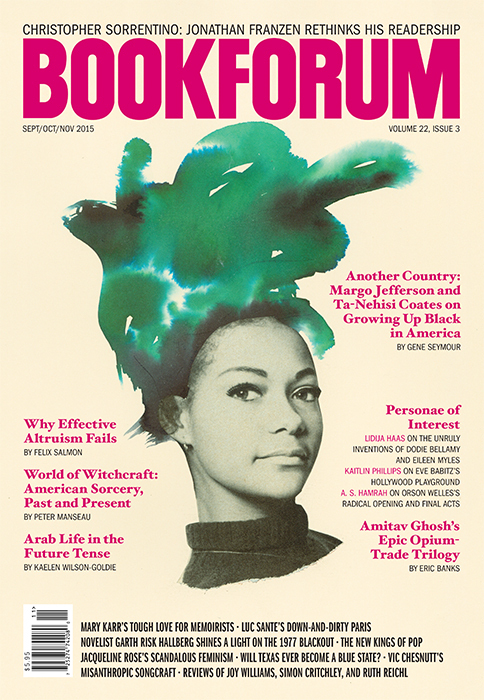

Eric Banks, the former editor in chief of Bookforum, is the director of the New York Institute for the Humanities.