“I’ve written a number of essays the past few years,” Dodie Bellamy writes in her new book, When the Sick Rule the World, “and I keep vowing to quit.” We know her essay-quitting hasn’t been going well, not only because we’re reading about it in a Dodie Bellamy essay, but also because these words, which originally appeared in the 2008 chapbook Barf Manifesto, are now nestled in a new collection alongside thirteen other essays, most of which have been written in the years since.

To be frank and detailed about sex in one’s writing, to use one’s own name and biography, to blend high and low cultural references in an intermittently casual tone, as Bellamy does, and to do these things while being a woman, as Bellamy is—all this might lead literal-minded readers to privilege what’s said over the way one says it, to fail to see the form for the subject matter. But for Bellamy, who came out of the New Narrative movement of the late 1970s and early ’80s, it’s form itself that’s juicy. She has published a post–Bram Stoker epistolary novel in which Mina Harker cuts a swath through AIDS-era San Francisco, possessing the body of Dodie Bellamy along the way; a blog-turned-book about her affair with a cultish Buddhist; a careful splicing of an erotic text into part of the 1975 Norton Anthology of Poetry. Not to mention a personal essay that begins with a set of seventy-eight “TV sutras” (“Stops more leaks than the next leading brand. End of tampon commercial. COMMENTARY . . . Distraction and lack of focus are also forms of leaking: losing track of what is valuable and meaningful”). No wonder she says she is “addicted” to the essay, yet at the same time has always found it “oppressive, a form so conservative it begs to be dismantled.” And she doesn’t merely want to deconstruct it, or to question it in the manner of a “feminist poetic essay” of the early ’80s. That kind of experiment “felt too watery for me. I wasn’t into watery, I was into libidinal”: Bellamy wants to fuck the essay (up).

Like any subversion of a form, this is an act of aggression, but also one of love, because it shows the form how much more it could be capable of—especially apt in the case of the essay, which by definition is always an experiment, an attempt to do or discover something new. “Barf Manifesto” takes as its starting point another essay, “Everyday Barf,” by the poet Eileen Myles, a ten-page feat that also begins with a fuck-you to strict formal convention. Myles describes being asked to write a political sestina, then having the editor who commissioned the poem critique its technical flaws. She is not interested in acing her homework assignment: “It simply strikes me that form has a real honest engagement with content and therefore might even need to get a little sleazy with it suggesting it stop early or go too far.”

As well as reading Myles’s work for us, Bellamy presents us with a portrait of the poet herself, and of their often tricky friendship (we see Myles, the more famous writer, maniacally destroying a piñata; we see her humiliate Bellamy after she clogs her toilet—“keep pumping,” Myles barks). Here Bellamy offers, both explicitly and implicitly, a way of thinking about the charged, rivalrous relations between writers and their influences, writers and their subjects, writers and readers. That’s one effect of the New Narrative practice of blurring those divides: Writers known and unknown show up in their own and their friends’ work; and they often present themselves as creative readers as well as writers, appropriating other texts in a particularly pointed fashion, not hiding or overprocessing the various foreign bodies they incorporate. In both cases the effects can be very complicated, because the texts are dramatizing several different kinds of power struggle: the obvious one in which the writer’s presentation of her subjects does battle with their own self-conceptions, but also others, in which, say, the writer grabs a brilliant passage from someone else’s work and tries to top it, or throws two incongruous, contradictory texts together and lets them fight it out.

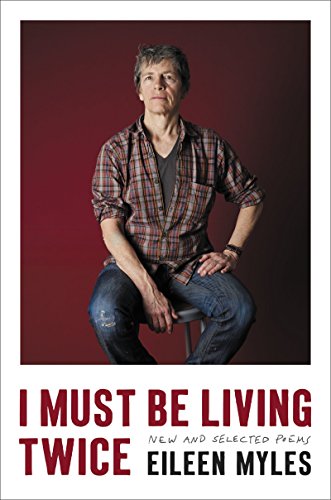

Myles’s selected poems are also being published this fall, along with a reissue of her notorious autofictional novel-in-stories Chelsea Girls. That book’s characteristically beguiling, wrong-footing directness of tone effectively covers any device Myles might care to use: She lulls the reader into a feeling of intimacy, of being confided in, but keeps letting us know, in hints and slippages, that at the same time she’s always artful, always playing games. It seems possible that the poetry volume, which includes poems from ten collections Myles published between 1978 and 2012 but begins and ends with new work, will mark her transition out of the in-between space she has long occupied, being passionately beloved in some quarters and chronically underrated in others. Rereading some of the poems, I wondered if Myles, whose trickster sensibility suffuses many of them as well as much of her prose, would feel any ambivalence about such a transition. Like Bellamy, she is interested in the complexities of power, status, and appropriation—in literature as well as everywhere else.

Take her unforgettable sixteen-line poem “On the Death of Robert Lowell,” first gathered in A Fresh Young Voice from the Plains (1981), which begins: “O, I don’t give a shit. / He was an old white-haired man / Insensate beyond belief and / Filled with much anxiety about his imagined / Pain. Not that I’d know / I hate fucking wasps.” And ends: “The old white-haired coot. / Fucking dead.” Despite appearances, in its gleeful energy it reads more as an attack on those who pay cringing, pious, self-serving tribute to such intellectual father figures (“these kiss-ass pieces in the Voice,” as she writes in her “poet’s novel” Inferno, “about his white hair blowing in the wind as he walked across Harvard Yard”) than on Lowell himself (“There are still people who are mad at me for it. People who went to Harvard, or wished they did, pretty much”). In her writing, Myles often clowns around with her own persona, manipulating parts of her biography (in what’s probably her best-known poem, she falsely confesses to being a closet Kennedy merely posing as an “obscure” lesbian writer) and poking fun at any conceivable anxieties over who is or isn’t a major poet. In Chelsea Girls, the narrator (who shares a name with the author) lists the loop of absurd possible dedications that runs in her head when she has to sign one of her books for Allen Ginsberg: “Hi Allen, from one howl to another. Dear Allen I’m glad you think I’m a poet. Love, Eileen. I’m the only woman you like, right Allen?” Ginsberg, like Lowell, has a level of fame that allows him to be easily instrumentalized, played with as a character: Both are in some sense understood to be up for grabs.

Her description in Inferno of a group reading tour that included Kathy Acker is spikier. The narrator (again named Eileen) recalls reading a usually showstopping poem to no response and realizing the crowd was mesmerized by live footage of Acker’s arm being projected on a huge scale on a screen behind her: “I am the backup singer to Kathy Acker’s fucking tattoos.” It’s hard not to think of this scene when reading Bellamy’s essay “Digging Through Kathy Acker’s Stuff.” What’s eerie is the similarity between the power struggles that seem to spring up around Acker both before and after her death, as if the time between has collapsed entirely. Bellamy talks about the “trail of victims” Acker left in her wake, and how many of them are now taking revenge by plotting their own conferences and readings, trying to control Acker’s posthumous image. She describes not wanting to touch Acker’s ashes at an impromptu ceremony at Robert Glück’s house where everyone else is using a spoon to transfer them into a fancier receptacle. She visits the artist Kaucyila Brooke’s LA studio to see her photographs of Acker’s clothing: “fantasizing about the pictures is like playing with dolls.” Bellamy takes an “unwashed Gaultier dress” from a box of Acker’s stuff and tries to imagine it as a doll, but finds it won’t comply, there’s too much presence in it—“it sits there haughty as a popular girl who refuses to talk to me.” Myles writes of the living Acker that her work was “so artificial and ritualized,” that she constructed a persona and “made that corpse walk night after night. She bought these expensive outfits. . . . It cost hundreds of dollars for her to look like a doll.” This static kind of charisma, which retains its power in unaltered form long after the performance is finished, is almost the inverse of the effects often achieved by Myles and Bellamy, who in their different ways draw attention to the present moment and what unpredictable things might happen there. Myles herself is charismatic without ever threatening to become iconic: Her persona is not the kind that inheres in her clothes.

Acker famously came from money, and Bellamy quotes her, from “The Birth of the Wild Heart”: “I was wild because I was protected—I could do anything.” Not so Bellamy or Myles, both of whom grew up working-class. You never get the feeling, reading either of them, that too much comfort made them adventurous. The element of boldness and risk often present in their work is all the more striking because it doesn’t feel purely aesthetic: Both of them appear to put themselves at stake, and to know what it means to do so without much to fall back on. Both also have the impulse to expose what you don’t expect to see, to write about people who are otherwise private citizens, who the reader senses may not want to be (or even anticipate being) written about—another act of loving aggression, a higher-stakes one, as it’s against the person rather than the form. In Chelsea Girls, Eileen knows that “every time Chris saw that I used her in another story she would get really upset.” She wonders “what anybody thinks about using your own life,” with “the actual words people say to you in the secrecy of love, or separation, or the oblivious moments when they’ve simply torn off an insult and flung it at you and you’re the one who remembers every little word.” Who owns the copyright on whose life? It’s a question that’s posed here at the end of the penultimate story: “I would like to tell everything once, just my part, because this is my life, not yours.”

A major part of the feeling of risk in writing that names names, that tells you about other people, has to do with time, the moment of being told a secret. Secrets are inherently time-bound: They exist very much in the present, containing the suspense of when they may be revealed. And in the case of someone being written about, you may be finding out before they do. “At the risk of pissing her off for all time because we are friends again,” Eileen writes of “Chris” in Chelsea Girls, “she looked like a shrimp curled up there . . . she looked like a fetus, a wet fetus crying.” Again, the deceptive plain-spokenness makes the reader feel present, intimate. We’re being told something about Chris that Chris, who’s still around, or around again, won’t want told. We’re in the risky present where Eileen is putting her friendship on the line by telling a story about a friend behind the friend’s back, and it’s also the future relative to the content of the story. For something told so simply, this screws with time to a surprising degree: Here’s a shrimplike fetus that already cries like a baby. This is a specialism for Myles, to create and simultaneously undermine the impression of sharing a moment with you.

In his “Long Note on New Narrative,” Robert Glück observes that “transgressive writing is not necessarily about sex or the body—or about anything one can predict.” Instead, it messes with what was traditionally perhaps the biggest boundary between writer and reader: “Transgressive writing shocks by articulating the present, the one thing impossible to put into words, because a language does not yet exist to describe the present.” In different ways, Bellamy and Myles prevent you from forgetting where you are, creating a sense of immediacy while continually jolting you out of it, whether by switching tenses or registers in midstream or by suddenly allowing another voice to intrude. What makes reading Bellamy such a physical experience, for instance, is the awareness of one’s own body reading there, not the content of whatever she exposes about hers. And the sense that any subject matter or material could potentially be brought in also physicalizes the act of writing; the impression is of a voracious text that is attempting to swallow the world around it at any given moment.

In “Barf Manifesto,” Bellamy notes that Myles in her barf essay “tracks how the personal intersects content intersects form intersects politics,” which her own work also aims to do. “Everyday Barf,” in Bellamy’s analysis, is structured like vomit: “Three gags followed by a tour de force rambling gush that twists and turns so violently, it’s hard to hold on to it.” Myles “spews recountings and opinions that frequently devolve into onomatopoeic grunts, such as ‘urp, wha wha wha, harrumph, blah, splat.’” The notion of writing as spewing is a complicated one: a fantasy of easeful productivity for any writer, but also a threatened accusation of unfiltered confessionalism for a woman using her own life and feelings as material. It evokes something uncontrolled and transgressive, and at the same time an almost impossible kind of rigor, a reaching toward a form that is not one, that is entirely transparent. The effect, whether achieved quickly or slowly, is still just that. Bellamy reports asking Myles how she accomplishes her self-concealing form, and being told that “she spends an hour planning the transitions, for if you have the transitions down, you can say anything.” (Myles’s “Writing” begins: “I can / connect // any two / things // that’s / god // teeny piece / of bandaid.”)

The transitions are precise because they have to be: It takes some doing to cram into one ten-page sweep the number of formal, political, and emotional insights and registers Myles manages (among other things, there’s the titular vomit-fest on a boat, guilt toward her mother, Bob Dylan’s memoir and the pointlessness of telling “the whole story,” class prejudice seeping through and compromising political protest, and the tradition of “accidental clown death” in her family: “My father died like that. Fell off the roof. Splat.”). Bellamy’s “Barf Manifesto” is likewise deftly stitched together; it’s in fact two separate essays, the second incorporating Myles’s reaction to the first. Barf, Bellamy says, is an “unruly” feminist mode “born of our hangover from imbibing too much Western Civ,” but each wave of it “calls forth a framing.” She observes, too, that the original Myles essay shifts with every reading and that “with each iteration I could write another frame recontextualizing Eileen’s and my Barfs, and the piece could reflect and expand ad infinitum.”

For Bellamy (and Myles too for that matter), the question of the frame is always a central one: It’s not just that you see things differently depending on perspective, but that the same thing in an altered context is utterly different. There’s a moment in the last, newest essay in Bellamy’s collection, “In the Shadow of Twitter Towers,” an antic, gruesome caper through the gentrification of San Francisco, when the marginalized people who resort to fucking by the Dumpster in a vacant lot across the alley are replaced by a condo owner in the same space, who continues the tradition of public sex behind vast glass walls, in her “million dollar jewel box.” (Here Bellamy lets a number of dark jokes make themselves; impossible not to notice, for instance, that privacy does not concern the condo owner, since she already has the kind that counts—private property.)

Partway through a short essay at the end of I Must Be Living Twice, Myles writes: “One thing I want to say also at this moment is that everything I’m describing so far has happened on my computer. Or in it.” The Internet is another place where form threatens (emptily) to disappear altogether. It can become nearly invisible, and yet it’s all you have—in an environment awash with content and information, any given piece of writing must rely primarily on its framing, on how it’s constructed and what it allows in. In his essay, Glück asserts that he’d wanted to write with “a total continuity and total disjunction since I experienced the world (and myself) as continuous and infinity divided.” This is an apt description of life online. It feels less remarkable now than it once was to stage (and undermine) a telling of secrets in public, or to conceal artifice behind an apparently unfiltered style. (Myles may be one of those writers whose influence is so pervasive as to obscure the evidence of it.) In the last pages of her book, Myles, clearly untroubled by the possibility of others assuming, as a critic famously wrote about Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, that her works are more “secreted” than written, speaks of having a “gland” that produces a particular sort of poem, and of the resulting poem as “her residue. Just a puddle on the page of what she’s felt.” It’s another performance of unfilteredness. In any case, long before widespread Internet use, Myles and Bellamy had already been finding ways to bring the time of reading so close to the time of writing as to smash right into it.

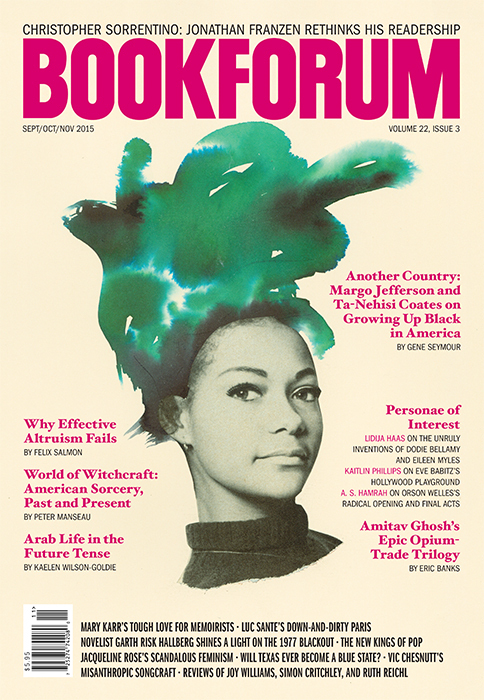

Lidija Haas is Bookforum’s associate editor.