Your soul mate is emotionally unavailable. He’s a bastard! He’s a narcissist. (So are you.) He’s great in bed, but he’s a workaholic. He’s an alcoholic. He’s a junkie. In strictly mechanical terms, your apartment is literally too small to have sex in. Let’s not talk about the size of your heart. The plight of the homeless does not move you. You personally haven’t called home in years. You have no shoulder to lean on; all your “friends” want to eat you alive. You’ve been forsaken by humanity. You’re a New Yorker.

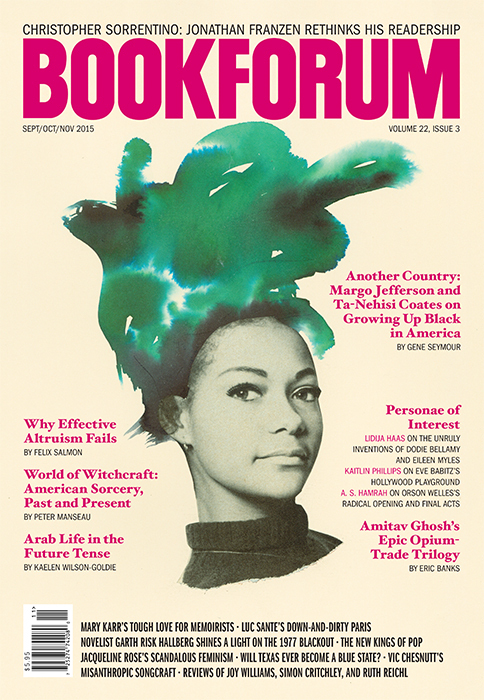

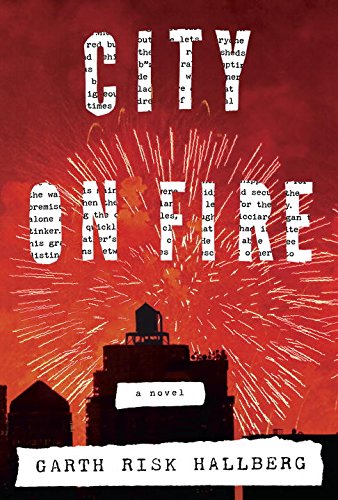

Loneliness plagues the heroes of Garth Risk Hallberg’s debut novel, City on Fire. They are lonely because they are selfish, and they are selfish because New York has deformed them; because life in Manhattan, that small but crowded island, is like a vast conspiracy to ignore the existence of other people. As if New Yorkers’ usual unneighborliness weren’t enough, the novel takes place in the 1970s, a decade of the city’s history notable for its peep shows, murders, fiscal crisis, and disillusioned gloom. City on Fire partakes of the dysfunction. It begins on New Year’s Eve, 1976, with the (fictional) shooting of teenage beauty Samantha Cicciaro in Central Park, and it climaxes on July 13, 1977, when all New York lost electricity for twenty-five hours.

When the lights came back on, 3,776 people were arrested—the most in one go in New York history. “The looters were looting other looters,” an eyewitness has said. In Hallberg’s novel, there are looters, but there are also dancers; the blackout is even a good thing. When the city goes dark, the differences that normally keep New Yorkers insulated from one another are obliterated. It is like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Manhattan edition. Complete strangers have sex with almost no preliminaries. On the other hand, the blackout is also, as Hallberg recognizes, a disaster. Mobs form, children are abandoned to the mercies of strangers, and the meek rise up from their basement apartments to commit arson—it is Walpurgisnacht. It seems a city can’t have dancing in the streets without rioting too, the price of universal togetherness being, more or less, total chaos. If the island of Manhattan is to function, must every man be an island? It’s a question that has struck a chord. Knopf paid nearly $2 million for Hallberg’s manuscript. The Hollywood producer Scott Rudin has already acquired the film rights.

“In New York, you can get anything delivered,” goes the first sentence of City on Fire. The sentiment is subtly desolate, as delivery always is, being a comment on what you don’t have at home. By the novel’s end, the tone is more social, the bad vibes having dispersed in magic words. “You are infinite,” Hallberg writes. “I see you. You are not alone.” It’s easy to hear the Whitman of “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” in the simple address of these lines (“It is not you alone, nor I alone”), which confirm that this is literature with a therapeutic intent.

How to take this is not immediately clear, and perhaps it is not meant to be, for City on Fire is miscellaneous and mystifying. Its postscript asserts that the book in one’s hands is, in fact, a conceptual artwork called Evidence III, the creation of William Hamilton-Sweeney III, one of City on Fire’s characters. And then there is the text itself, which has been made willfully strange—by varied typefaces, inset Xeroxed documents (zines, typescripts, paperwork), even a few vérité typos. The whodunit plot is, likewise, self-deflating. Starting strong, the story of Samantha’s shooting loses steam as it cuts back and forth across time until finally time itself, the very back-and-forthness of it, overtakes her as the novel’s engrossing subject.

As in the fiction of Saul Bellow, Hallberg’s heroes are theorists of their own universe; they not only occasion deep thoughts but have them. But it is hard for literary characters to theorize without implying a theory of literature, and frequently metaphysics verges on metafiction. A gay black writer, Mercer Goodman (also, William’s unhappy boyfriend), dreams of writing a book about “America, and freedom, and the kinship of time to pain.” The journalist Richard Groskoph, who will become obsessed by Samantha, wants to “to follow the soul far enough out along these lines of relationship to discover that there was no fixed point where one person ended and another began . . . to be, not infinite exactly, but big enough to suggest infinitude.” How would a book like that look?

City on Fire’s story concerns a dozen or so New Yorkers who have little in common, at first, beyond their conviction that they have nobody. “It seemed to him,” thinks Charlie Weisbarger, a teenager on Long Island and Samantha’s best friend, “that every person on earth was sealed in his or her own little capsule, unable to reach or help or even understand anyone else”—a vision of confinement Hallberg returns to repeatedly. And in Samatha, the victim of the New Year’s Eve shooting, whose wounds have rendered her comatose, it is literalized: Her solitary confinement is a medical condition.

It’s a paradox typical of City on Fire that Samantha’s inability to connect will draw all into her orbit—that her inner blackout will let others see past themselves. “All these threads, like the ley-lines he’d read about in his Time-Life history books, converging on the Cicciaro girl, who lay there unaware, a glass-coffined beauty whose kingdom was in ruins,” thinks the Staten Islander Larry Pulaski, the detective on Samantha’s case. The novel follows multiple routes to Samantha’s bedside. Every ley line is a life story, every subplot a window on a New York niche. Samantha was a devotee of punk and a comrade of anarchists, a friend to Charlie and a mistress to Keith. Her father, Carmine, was a famed Long Island fireworks-maker being profiled by Richard. Mercer found her unconscious body in Central Park and saved her life. Will, you might say, saved her soul. His defunct punk band, Ex Post Facto (it’s from their lyrics that the novel takes its title), obsessed both her and Charlie. Magnetic, high-handed, and breezily promiscuous, Will might be a stand-in for New York itself.

It all amounts to an epic nostalgia tour—Long Island fireworks-makers who eschew machines (now robots do it), WASPS who rule Wall Street (now the “data machine” runs it), the New Journalism (now old), the cruising scene (pre-AIDS), the heroin scene, the punk scene, even policework itself. (“To be a cop at this late date in history was to be, by definition, a nostalgist,” thinks Pulaski, in 1977.) Patti Smith doesn’t just perform “Piss Factory” in the East Village; she delivers a pep talk to a heroine—in a dream. The story itself is dramatic, intermixing a police procedural with a terrorist plot, an addiction plot, an art plot, various adultery plots. The book’s villain is described (twice) as “the motherfucking devil.”

The result is a narrative that is immense; that is, it seems deliberately, overwhelming. It is meant to make you feel for the overwhelmed. “The most amazing thing was how much richer their lives were than she’d imagined,” thinks Jenny Nguyen, having overheard from her little apartment a woman upstairs experiencing orgasms. “These people extravagantly alive in these contexts all around her, while she, a singleton, sat alone.” For Jenny, the sound of strange orgasms through her ceiling is the beginning of empathy. Will she ever meet these people, she wonders? Can their context be her context?

On this social-practical question falls the shadow of a literary-technical one, which different characters are deputized to explain. Richard dreams of a story like a firework—the “discrete plotting,” “each element in its own compartment”—whose diverse parts would explode all at once. The problem, as Charlie puts it, attempting to map out a comic book, is “how to fit the simultaneity of things into relentlessly forward-moving frames.” “Time seemed like an arrow,” he thinks, “only because people’s brains were too puny to handle the everything that would otherwise be present.” Simultaneity is a great fantasy of writers because it is, of course, impossible. Narrative is sequential—one thing after another. And yet, Charlie suggests, perhaps this is small-minded. Perhaps a perfect story would give “the everything” all at once, a “baffling integration” of a “baffling multiplicity.” It’s the conceit of Hallberg’s novel to equate this vision of simultaneous prose with the vision of a utopian New York.

This dream of togetherness also inflects Hallberg’s sentences. They cram and scoop and heap in all they can; they are melting pots of rhythms and idioms. “And yet there was this dissembling body,” he writes of Richard,

this conglomerate Richard, returning to the kitchen, reiterating that he was sure Samantha would be okay (which he wasn’t), and that Carmine should get some sleep (which he probably couldn’t), and just generally knitting that doily of horseshit you were expected to insert between the bereaved and the fact that no one, in the end, made it out of this life alive.

Readers of David Foster Wallace may find this artfully oralish style familiar—the performances of hesitancy (“which he probably couldn’t”), the mixture of Latinate (“conglomerate”) and earthy (“horseshit”) diction, the offbeat and off-color metaphor. It is a dialectical mode, writing founded on the linking of the unalike.

Its effect is to pile on oxymorons. Love is a “powerful powerlessness,” the sweetness of children a “thoughtful thoughtlessness.” “Irony and sincerity,” thinks one character, “might co-exist.” The blackout deepens these paradoxes without resolving them: The protagonists come together as their city falls apart; their souls meld as their identities disintegrate. Will comes out to his estranged father, but his father, now senile, falls asleep. Jenny sleeps with a man she has struck with her car. Is it transcendence, or is it cheap? If you screw a stranger in the dark, are you connecting with somebody else? Or are you losing yourself? The evidence is, you might say, ambiguous. Raising more questions than it answers, Hallberg’s novel spins with its heroes rather gloriously in this dialectic of dark and light, among complexities from which the soothing simplicity of its final lines could not be further. “Let no one tell you you didn’t change into something else last night, New York, if only briefly,” says a radio DJ. “It’s been enough to make me think maybe I can change, too.” It’s the kind of thought you have in the morning, right before you turn on the light.

James Camp is a writer living in New York.