The socialist Rosa Luxemburg met her lover and lifelong collaborator Leo Jogiches at a student-radical club in 1890. Luxemburg was nineteen. Jogiches, a few years older than her, was known for his severity and single-minded devotion to the cause. She was drawn to his zeal, and within a year they were a couple, but not a happy one. He resented her success, refused to be seen with her, and tried to control where she went and what she did. When he found out she was seeing someone else, he threatened her with a gun. Luxemburg’s letters to him, written over a period of two decades, show her begging him for affection and describing the “painful bruises” he left on her soul.

What place should this relationship, which we would now label as abusive, have in Luxemburg’s biography? To give it too little weight—to claim that Luxemburg’s private affairs had nothing to do with her public life—severs the link between her roles as a woman and as a political actor. To give it too much weight risks overshadowing her substantial achievements by turning her into a victim or a martyr.

This is the dilemma posed by Jacqueline Rose in the opening chapter of her new book, Women in Dark Times. She places Luxemburg’s letters alongside summaries of her most influential ideas. Juxtaposed with her political writings, Luxemburg’s long and wounding arguments with Jogiches come to seem like a rehearsal for her public career. Her letters accusing him of being narrow-minded and controlling draw on the same vocabulary she went on to use in her critique of Lenin’s authoritarian tendencies and her theory that revolutions and mass strikes could never be reliably predicted or fully managed. “To the immense irritation of her opponents and detractors,” Rose writes of Luxemburg, “she elevated the principle of uncertainty to something of a revolutionary creed.”

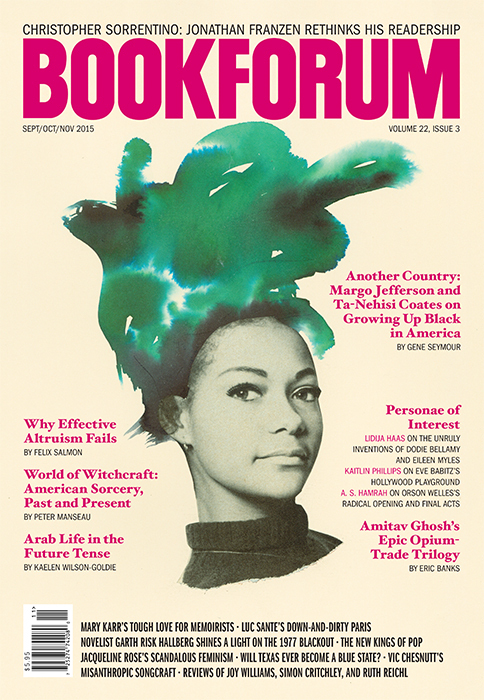

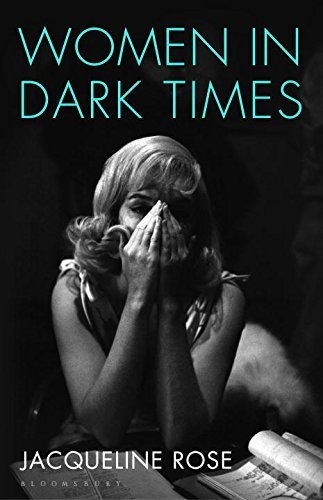

Rose finds her own richest material in this kind of productive uncertainty. She has long been interested in the mutable space between our inner lives and our actions. A professor and prominent literary scholar, Rose uses psychoanalysis as an important tool in her political and social commentary. Much of her early writing, informed by feminist theory, concentrated on women as a focal point for collective fantasies that blur the distinction between the subterranean mind and the social world. She has since examined subjects as wide-ranging as Zionism, nationalism, and the disciplinary boundaries of literary study. Women in Dark Times is her first straightforwardly feminist work since 1991’s The Haunting of Sylvia Plath, her foray into the bitter controversy over the poet’s legacy.

Although Women in Dark Times takes up similar themes, it represents a marked shift from the majestic distance and impersonality of that earlier book, in which Rose insisted that she was not writing a biography and referred to Plath and Ted Hughes as “textual entities” rather than as people. A collection of loosely joined biographical essays modeled after Hannah Arendt’s Men in Dark Times (1968), her new volume brings together a range of disparate subjects: Luxemburg, Marilyn Monroe, the victims of honor killings, and several artists Rose admires. The question that binds them all together and provides the momentum of the book is: “How to think of women as subjected but not—solely—the victims of their lives?”

This question is not new, but it is well timed. Over the past several years, the conflict between asserting women’s agency and recognizing their victimhood, a perennial feminist tension, has been reignited by a new wave of online activism informed by trauma theory and spread on college campuses and through social media. In response to liberal feminism’s emphasis on individual empowerment, these activists have argued for a politics of collective vulnerability, based on the idea that women are subject to specific forms of violence: on one side, Sheryl Sandberg, Hillary Clinton, Beyoncé posing as Rosie the Riveter; on the other, affirmative consent codes, trigger warnings, and safe spaces.

Rose’s book aims to complicate the terms of this debate. It begins with a call for “a scandalous feminism, one which embraces without inhibition the most painful, outrageous aspects of the human heart” and attempts to bridge the gap between images of women as perfect agents and perfect victims. Women in Dark Times is an earnest, occasionally goofy paean to “women who have taught me how to think differently.” It is full of affectionately evoked details of its subjects’ lives—Luxemburg was a passionate cyclist; Monroe once warned suspected Hollywood communists of a police raid—and words like brilliance and genius.

It is also a catalogue of the forms of violence, both individual and historical, that touched the lives of Rose’s subjects. The book can read, at times, like a taxonomy of injury: depression, addiction, incest, abuse, suicide. Rose writes about Monroe’s institutionalization and Luxemburg’s death at the hands of the Freikorps, Germany’s proto-Nazi militia. One essay, on honor killings, describes a teenage girl whose father stabbed her, then slit his own throat and jumped from a balcony.

In all these stories, Rose tries to brings to light the hidden ties between forms of suffering we think of as public or historical and those we dismiss as merely private or internal—a line of feminist argument running back to Virginia Woolf’s analogy between fascism and patriarchy in her antiwar essay Three Guineas. Women in Dark Times begins with biographical studies of three historical figures—Luxemburg, Monroe, and the German-Jewish painter Charlotte Salomon—whose lives were shaped by the worst political catastrophes of the past century as well as by characteristically female forms of personal trauma. The strength of Rose’s essays lies in how she teases out the tangled threads in her subjects’ lives without reducing history to psychology or attributing internal pain solely to external causes. Instead, she tries to show the complex ways in which these three women (her “stars,” as she calls them) were themselves able to draw the connections between both spheres of their lives—an activity she sees as central to their creative talents.

The remainder of the book extends the two strands of Rose’s argument into the present. In the second section, “The Lower Depths,” she presents a detailed analysis of the phenomenon of honor killings in European migrant communities, one that goes beyond a simple condemnation. In the third, “Living,” she writes about the work of three contemporary artists—Yael Bartana, Esther Shalev-Gerz, and Thérèse Oulton—whom she praises for bringing their experiences as women to bear on a cross section of urgent political issues, including the gaps in postwar European memory, extreme right-wing nationalist movements, Zionism and anti-Semitism, and the destruction of the environment.

Of the three historical biographies at the heart of the book, Salomon’s story may be the grimmest. Killed in Auschwitz in 1943, she was born into an educated Berlin family with a history of clinical depression. Seven of her relatives committed suicide, including her aunt, her mother, and her maternal grandmother. The circumstances of their deaths were kept private; Salomon, who was eight when her mother killed herself, was told she had died of the flu and didn’t learn the truth until fifteen years later.

Salomon’s major work, “Life? or Theater?,” is a series of more than seven hundred individual gouaches that combine images, text, and musical notations written out on transparencies that overlay each page. Created in a burst of energy after she discovered the details of her relatives’ deaths, it traces the linked stories of the rise of Nazism in the aftermath of World War I and her own family’s history. In the vivid, bleeding outlines of their figures and in their wild mix of genres, Rose sees Salomon’s effort to create a new kind of language, one able to express a critique of both fascism’s intolerance for imperfection and her own family’s denial of its past.

Rose is struck in particular by the contrasting depictions of Salomon’s absent family members, often lovingly memorialized on one side of a page and defaced by strips of tape that cover their mouths and eyes on the other. In these two-sided images, Rose perceives an illustration of the basic ambivalence of psychic life; part of her aim in the book is to denounce collective fantasies that deny or cover up this reality. If feminism is to have any unified political project beyond securing women’s equal access to power, she insists, it lies in exposing the protective fictions of mastery and control that still play a disproportionate role in our public, as well as our private, life.

Throughout her essays, Rose praises her heroines for their combination of clarity and uncertainty, and this is not a bad description of Women in Dark Times itself. In her attempt to speak to a broader audience, she sometimes presents the conclusions of complicated theoretical positions as self-evident. At times, she seems to be free-associating, jumping forward or backward in time or returning to points she’s made before, moving, for instance, from Luxemburg’s theory of capital accumulation to Naomi Klein to the 2011 earthquake in Japan.

But if Rose’s sometimes chaotic enthusiasm is a departure from her usual magisterial composure, it is surely no accident. Her book’s central point is about the importance, and the difficulty, of acknowledging and valuing unpredictability, ambiguity, and contradiction. To this list of virtues we might also add the willingness to risk appearing a little unreasonable—scandalous, even—in public.

Namara Smith is an associate editor of n+1.