One day in 1974, Orson Welles, John Huston, and the comedian Rich Little were sitting in a Denny’s near Carefree, Arizona, about to order a meal. Huston and Little were acting in Welles’s new film, The Other Side of the Wind, which is still unfinished and unreleased and was then in its fourth year of production. Welles was living in a desert house nearby, a rental in which he was also shooting his movie, something he had neglected to tell the owners he’d be doing.

Rich Little was a television star at the time, a popular nightclub impressionist seen on an ABC variety show called The Kopykats and on Dean Martin’s TV roasts, which often included Welles. Welles had hired Little to play the second lead in The Other Side of the Wind, a choice that raised eyebrows. Welles wanted Little because he needed someone who could do voice impressions of Hollywood stars, not because he thought Little was a great actor himself. His character in Welles’s semiautobiographical film was based on Peter Bogdanovich, the young director of The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon and a Welles acolyte known for his ability to mimic the voices of movie greats.

A waitress approached the table where the three men sat. She recognized Little right away. After bantering with the impressionist for a bit, she nodded toward Welles and asked Little, “Who’s your fat friend?”

Huston, saving the day, answered for Little with a straight face. “You know, we don’t actually know this man,” he said, indicating Welles. “We picked him up on the highway and he seemed undernourished. We’re going to feed him and then send him on his way.”

The story comes from Orson Welles’s Last Movie, a recent book by Josh Karp. It’s one of many anecdotes designed to show how low the mighty director of the greatest movie ever made fell after completing his first and only masterpiece, Citizen Kane, in 1941. See the Boy Genius three decades later, fat-shamed at Denny’s.

Further passage of time, however, has put stories like this one in a different light. Welles’s detractors have been trying to punish him for his uncompromising approach to filmmaking—a directing style that looked, especially to Hollywood traditionalists, unorthodox—since before Citizen Kane was even released. By 1942, the year RKO butchered his second film, The Magnificent Ambersons, and blamed Welles for his own film’s disfigurement, the myth of the self-destructive auteur was already in place. But now when we look back on Welles’s work in Hollywood in the early 1940s, his real problems become clear: His dark vision of American capitalism was out of tune with the gung-ho years of World War II. That Welles pursued his original vision, even as he worked in a state of hand-to-mouth auteur financing, into the ’80s looks from our vantage point like a sign of strength and integrity. The director of Citizen Kane and the director of The Maltese Falcon sitting in a Denny’s in Arizona with Rich Little in 1974? That is a picture of dignity in the face of adversity, not a picture of failure.

It’s been difficult to get beyond the mocking portrayals of Welles in part because so many critics and pop film historians have adopted Hollywood’s conformist notions of success. Welles’s story of uncompromising ambition and lack of concern for studio approval has functioned as a cautionary tale: a lesson in how not to succeed in show business. Writers of the early ’70s, such as Charles Higham and Pauline Kael, worked hard to knock Welles off a pedestal Hollywood had already smashed. Other writers have scraped away at the great man’s self-image, marring it the way scratches on film tear into the emulsion and make it harder to see. Some continue to punish Welles. For a recent example, check Peter Biskind’s introduction to the book My Lunches with Orson, a series of transcripts from tape-recorded conversations the filmmaker Henry Jaglom had with Welles in the LA restaurant Ma Maison between 1983 and 1985, the year Welles died. Biskind can’t resist reveling in Welles’s last days, when Welles “had ballooned to the size of a baby elephant” and survived by appearing in “B movies produced by fly-by-night producers in no-name countries” and “odds and ends like soaps, game shows, and TV commercials.”

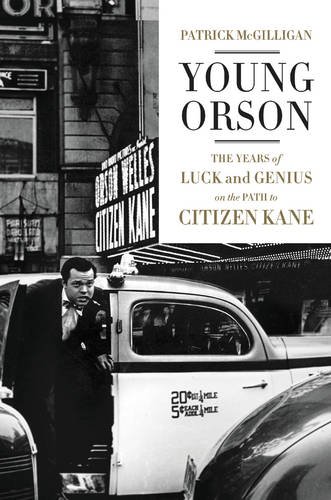

But this year, the Welles centennial, an appreciation for Welles—even the late, bloated, talk-show-guest Welles—is gathering force. Karp’s book, along with Patrick McGilligan’s remarkable, eye-opening biography Young Orson and A. Brad Schwartz’s Broadcast Hysteria, provide a deep, nuanced portrait of the director at the start and finish of his career. By skipping his better-known and much-studied years as an actor-director in Hollywood in the heyday of the studio system, and his years in the ’50s and ’60s as a nomadic filmmaker in Europe, these studies offer a new image of Welles, one that re-radicalizes him as an artist and sets him against the backdrop of the Depression and the early days of World War II. Focusing on his work in the theater and radio in New York and elsewhere in the ’30s, then cutting, Kane-like, to the New Hollywood of the ’70s reveals an unwavering Welles, committed to a kaleidoscopic vision that was also a style of work and a way of being in the world. If he failed to find a way to direct his films with Hollywood funding and approval, he went elsewhere—a rebuke the movie industry saw as disrespectful, self-sabotaging, and grotesque.

While the cautionary Welles is a great source of Internet listicle kitsch (“16 Hilarious Examples of Orson Welles’s Late-Career Slumming,” flogged a headline on Newsweek.com earlier this year), it is not the Welles we need in the twenty-first century. The Welles of TV talk shows and wine commercials is in fact an indictment of how the second half of the twentieth century failed to live up to the promises of the first half. In reality, it wasn’t that Welles did not fulfill his promise. The times let him down.

In that sense, Welles’s career started as it ended. When he was five years old, he got a gig dressing up as the White Rabbit at Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago, hopping around and announcing, “Oh, I must hurry—or else it will be too late to see the woolen underwear on the eighth floor!” Welles called doing advertisements “the most innocent form of whoring,” and even on radio the sponsor-free Mercury Theatre on the Air eventually became the Campbell Playhouse, introduced by long ads extolling the virtues of hot soup. Welles went on to become, as one historian quoted in McGilligan’s book describes him, “the American Brecht, the single most important Popular Front artist in theater, radio, and film, both politically and aesthetically.” But he never seemed to worry about maintaining a claim to purity: In some ways, he was always willing to step back into the bunny suit, if it could make him the money he needed for his next film or theater piece, or if it fit his strange view of American entertainment.

Welles recalled his childhood as “one of those lost worlds, one of those Edens that you get thrown out of.” He grew up in idyllic towns with names like Oregon, Wisconsin, and Wyoming, New York, places that sound like they were invented by Franz Kafka for his novel Amerika. Welles’s politically progressive mother and father encouraged his precocity and indulged his dramatic bent, taking him to the theater, magic shows, and concerts. As a child, Welles had seen on the stage many of the actors he later cast in plays and in his movies. Agnes Moorehead, who played Charles Foster Kane’s mother and George Amberson Minafer’s aunt in Welles’s first two films, acted with Welles in the radio series The Shadow. Fifteen years older than him, she remembered seeing Welles as a nine-year-old in the lobby of the Waldorf Hotel in New York City after Igor Stravinsky’s American debut, and listening to him pontificate on Stravinsky’s music to his father. With his “shock of black hair,” Moorehead remembered, “he was fantastic, the way he kept explaining his feelings about the concert.”

“Less than a year after the death of his own mother,” McGilligan observes, “he had met her fictional counterpart.” Welles’s childhood, so like a Wes Anderson movie, was shaped by his parents’ divorce and their early deaths. His mother, a pianist, elocutionist, and suffragist, died of a liver ailment when Welles was nine. His father, the inventor of an automobile headlight and a successful businessman who retired wealthy and young, slipped into alcoholism after he divorced Welles’s mother, and it worsened after her death. He died when Welles was fifteen, leaving him a trust fund Welles would collect in full when he turned twenty-five. A family friend, Dr. Maurice Bernstein, an eccentric surgeon and musician who provided the name for a character in Citizen Kane, oversaw the trust, doling out a hundred dollars a month.

Welles, established as his prep school’s resident artistic genius, declined a scholarship to Harvard and set sail for the Gate Theatre in Dublin. He convinced the artistic directors there, Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLiammóir, that he was eighteen. Sensing, in MacLiammóir’s words, “some ageless and superb inner confidence,” they cast the sixteen-year-old Welles in a play, setting a template for the rest of his career by assigning him the role of a man in his fifties. Welles’s entrance onto the stage was greeted, MacLiammóir wrote, with “a flutter of astonishment and alarm, a hush, and a volley of applause.” Welles took six curtain calls on opening night and his performance was reviewed favorably across the ocean in the New York Times.

For the next ten years, Welles was in a whirlwind, spinning at its center and gathering more force. After stints back in the Midwest, in New York City, and then in Spain, where he fought four professional bullfights (McGilligan confirms this much-disputed claim), Welles settled in Manhattan with his eighteen-year-old bride, Virginia Nicolson, also an actor, also from a prominent Midwestern family. They lived in a one-room apartment with a bathtub in the middle of the room, which they covered with a board at night to turn into a bed.

IT ALL SOUNDS VERY ROMANTIC, and it was. McGilligan’s Orson is a Welles for a new generation. His book has a quality more in tune with Patti Smith’s Just Kids (albeit a Just Kids that is eight hundred pages long) than with McGilligan’s similarly lengthy and authoritative biographies of Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang. Like Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe in their New York, Welles was hyperaware of his own status as a fledgling artist setting out to conquer the town. McGilligan’s book vibrates with uncertainty and risk, and it hums with the possibility that talented people actually can realize their dreams in the forms they choose. In the words, once again, of MacLiammóir, the book speaks of a time when “Orson had not yet found his true métier, which was a preoccupation with restless grandeur and intoxication, a view of life wholly American and welling up from the soil of the huge territory which had given him birth.”

Young Orson’s urgency is also a function of the kinds of theater and radio Welles was making in those years. McGilligan writes that he has tried to produce a book that is scrupulous but sympathetic to Welles, and his sympathy extends to the social-justice causes that animated the artistic life of young New Yorkers in the days of the New Deal, the WPA, and the Federal Theatre Project. The sources of Welles’s achievement in the cinema are there, but the roots of his later problems with authority, with the right wing, and with mass culture are there, too. Reactionaries lurk at every turn, ready to disparage Welles’s accomplishments and seal his fate.

Welles’s initial struggle was to earn enough money acting on the radio to pay for what he wanted to do in theater, and this he managed to do. His mad scramble, however, began a cycle which became the pattern of his life. His first success on the American stage came in late 1934, as Tybalt in a high-end but conventional production of Romeo and Juliet. It was there that John Houseman, who would become the Mercury Theatre’s producer and Welles’s lifelong nemesis, first saw him, reacting to his performance with a homoerotic thrill that later led to jealousy and resentment, and which replicated and reflected the older man/younger man dynamic of so much of Welles’s work. Welles’s first radical or avant-garde success came three months later in a production of the poet Archibald MacLeish’s play Panic, “a blank-verse autopsy of the U.S. banking crisis of 1933, complete with Greek chorus.” The nineteen-year-old Welles, in his performance as a middle-age banker, was “bluff, defiant, bullock-like and brutal,” according to a newspaper review. Houseman, in one of his memoirs, describes Welles’s voice in Panic as “an instrument of pathos and terror, of infinite delicacy and brutally devastating power.”

It was a voice for radio. Welles made good money as an anonymous actor on news shows like The March of Time, playing figures from the news of the day in staged re-creations of world events. At CBS he met actors like Joseph Cotten and Ray Collins, who later followed him to the Mercury Theatre and Hollywood. Even after the success of the Mercury Theatre on the stage and on the air, Welles continued to act for radio news. He had the strange honor of playing himself, uncredited, after the War of the Worlds panic became international news on Halloween in 1938.

The two years before the War of the Worlds broadcast were the most eventful of Welles’s life. Working with Houseman for the Federal Theatre Project’s so-called Negro Unit in Harlem, Welles directed a black-cast version of Macbeth, popularly known as the “Voodoo Macbeth.” Employing many nonactors from the neighborhood, this African American production was not the minstrel show some feared it might become, but a landmark production in American theater. (You can find footage of it on YouTube.) A cause célèbre, it attracted audiences from all over the city and solidified Welles’s reputation as a fighter for racial equality, a position that hurt him later. As an arch-lefty but noncommunist, Welles faced a soft exclusion from Hollywood that was conveniently attributed to his mythical unreliability.

The Mercury Theatre’s “fascist” Julius Caesar followed, by all accounts a staggering, even frightening production featuring Welles as Brutus that received but one mean review, from Mary McCarthy. Fearing attacks from anti–New Deal Republicans, the Federal Theatre Project then shut down Welles’s production of Marc Blitzstein’s pro-labor musical The Cradle Will Rock, padlocking the door to keep out the audience. Welles moved the crowd twenty blocks to a vacant theater and put on the show in the aisles with Blitzstein at the piano onstage.

A year later, Welles had too many plays in rehearsal, was doing too many radio shows, was taking Benzedrine to stay awake, ignoring his marriage, sending all-caps telegrams to ballerinas in an early version of sexting, and pushing his actors to work around the clock. He was overextended by the time the Mercury Theatre’s radio production of H. G. Wells’s novel The War of the Worlds hit the air. Changing the setting to contemporary New Jersey and presenting the radio play as a fake news broadcast panicked about a million listeners who had tuned in late, according to Schwartz in Broadcast Hysteria, causing them to believe a real Martian attack, or at least some kind of invasion or disaster, was under way.

Schwartz is careful in his excellent book to untangle the facts of what happened that night from the ways newspapers distorted the reaction, blaming it on hysterical women and residents of rural areas, or claiming Welles’s sci-fi drama was a hoax. Broadcast Hysteria studies the almost two thousand letters people sent to Welles, to CBS Radio, and to the FCC, many in appreciation of Welles’s show, but many outraged and condemnatory. One reader from the South wrote in to say Welles should be lynched.

This 1930s version of the comments section included much praise for Welles, too. A listener wrote that he had “put to shame the alleged master-minds of Hollywood and now they will be beseeching you with offers.” In fact, they had already called. Soon Welles was flying back and forth between New York and Hollywood, earning his status as TWA’s most-frequent flier that year, to do his radio show once a week while also preparing his first movie for RKO, under a contract that gave him complete control over the finished product. McGilligan follows him through that process, presenting excerpts from his bold first-person (and later abandoned) script for Heart of Darkness, chronicling the writing of Citizen Kane with Houseman and Herman Mankiewicz (an account that should finally lay to rest Pauline Kael’s assertion that Welles wrote none of that famous film’s screenplay). The book wraps when Welles calls “Action!” on the first day of shooting Kane.

Welles started his first film that day; he never finished his last. In May 2015, thirty years after his death, an Indiegogo campaign sought to raise a million dollars to complete The Other Side of the Wind, now that the film’s labyrinthine rights issues have been cleared up. The campaign page featured testimonials from well-known contemporary directors who were not giving money of their own, and offered premiums at different donation levels, including a white terry-cloth bathrobe with Welles’s signature and face emblazoned on the chest. The drive fell several hundred thousand dollars short of its goal. The producers say they will finish the film anyway. It is imperative that they do.

In the mid-1980s, Steven Spielberg bought a Rosebud sled from Citizen Kane at auction for $60,500. At the same time, Spielberg denied Welles the opportunity to direct an episode of his NBC television series Amazing Stories, instead opting to hire directorial talent such as Burt Reynolds and Timothy Hutton. According to Joseph McBride, who has written several books on Welles and also Steven Spielberg: A Biography, Spielberg, after buying the prop, said he saw it as “a symbolic medallion of quality in movies. When you look at Rosebud, you don’t think of fast dollars, fast sequels, and remakes. This to me says that movies of my generation had better be good.”

Maybe that’s why there has never been a Goonies sequel. Meanwhile, back at Denny’s, the summer 2015 menu features a pancake entrée called the “Invisible Woman Slam,” “drizzled with a clear citrus glaze,” part of a promotion for the new Fantastic Four movie. In Hollywood, Welles once said, they “make the kind of movie producers want to produce,” the kind written in invisible pancake syrup. That was not Welles’s goal in life. Whether we see him as an outcast or a genius, his story is the biggest argument against that system’s idea of genius.

A. S. Hamrah was the film critic and film editor for n+1 and writes for a variety of publications including Cineaste and The Baffler.