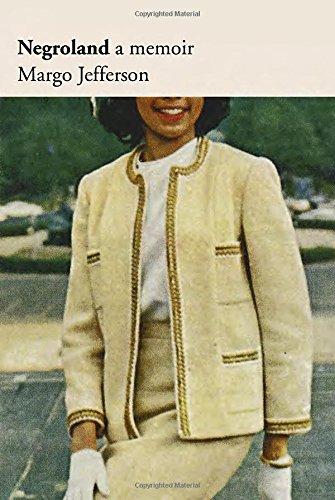

Fine. Let’s start with “Negro,” or, if one prefers, “negro.” Even with this word’s present-day, often lower-case status, there are African Americans for whom “Negro” is a trigger word for outrage or affront. Some want the word excised altogether—which, at least to this African American, displays amnesia toward (or, worse, disrespect for) our collective history. Between the years 1900 and 1970 (give or take), “Negro” defined a people in transition through two world wars, a cultural renaissance, and a social and political movement that changed everything around it. Those who defined themselves as “Negro” flew airplanes to battle fascism, made their own movies, established baseball franchises, and used their hard-won education in law, the arts, and science to pull their people ahead with them, transforming a nation that otherwise refused to see them as they were, when it chose to see them at all. Where that other “N-word” demeaned and distorted (and still does, no matter who uses it), “Negro” dignified and elevated. After the ’60s had run their course, Negroes collectively agreed to shift to “black” because the other was no longer considered sufficient, or useful. It was outdated, perhaps. But an insult? Our grandparents and great-grandparents might beg to differ, no matter what they chose to call themselves.

I am, in short, riding the same train as Margo Jefferson, who may be even more bullish on the matter than I am, certainly more lyrical: “I still find ‘Negro’ a word of wonders, glorious and terrible. . . . A tonal-language word whose meaning shifts as setting and context shift, as history twists, lurches, advances, and stagnates. As capital letters appear to enhance its dignity; as other nomenclatures arise to challenge its primacy.”

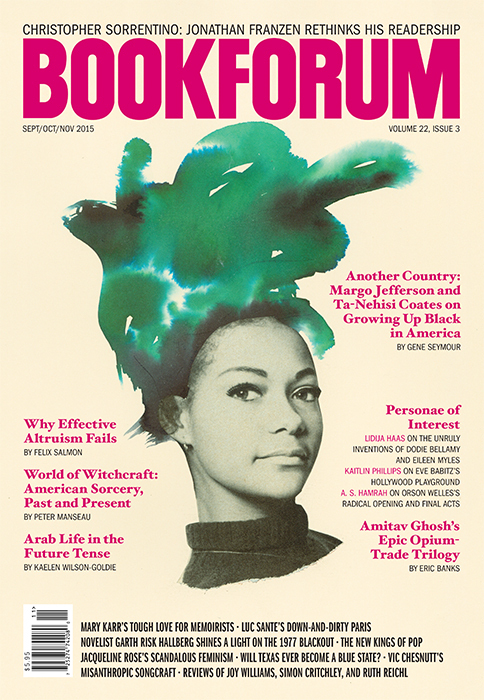

So it is more in avid interrogation than with jaded irony that this often misjudged N-word is emphasized in Negroland, Jefferson’s memoir of growing up black and privileged in Chicago during the ascent of the civil-rights movement in the ’50s and ’60s. She emerged at the other end of that upbringing as a noted feminist, seasoned journalist, and Pulitzer Prize–winning critic, who toward the book’s conclusion presents herself as “a woman who grew up as a Negro and usually calls herself black,” and who saves the term African American “strictly for official discourse.” If this elegant self-definition comes across as easily obtainable, the silken, wistful, and incisive narrative leading up to it assures the reader that it isn’t.

For as distinctive as Negroland is in its wit, composure, and erudition, it shares a core value with some of its illustrious predecessors, from slave narratives to the autobiographies of Booker T. Washington, Zora Neale Hurston, Malcolm X, and countless others up to and including this year’s Most Significant Book on Race, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, a riveting j’accuse for the age of Obama, hip-hop, and Ferguson. Negroland, the testament of a quintessential black baby boomer from the (relative) lap of luxury, shares with Coates’s book stunning rhetorical agility, rigorous introspection, and the rueful knowledge that every person of color has to be lucky, careful, or, most often, both when forging a self amid the dubious and mostly abstract mythology of race in America.

Both books know that the rigidly patrolled matrix of Difference can break your heart before it starts breaking you. This is true even if, as with Jefferson, your father was head of pediatrics at Provident, the nation’s oldest black hospital, and your mother was a social worker turned socialite who made sure you were schooled in comportment (not mere manners), compelled toward triumph (not mere success), and conditioned to make your advancement look effortless, even inevitable, despite the odds. “Nothing highlighted our privilege more than the menace to it,” she writes. She elaborates elsewhere:

We were taught that we embodied the best that was known and thought in—and of—Negro life. We were taught to resent the relative lack of attention our achievements garnered. We were taught that we were better than the whites who looked down on us—that we were better than most whites, period. But that this would rarely if ever be acknowledged by white people, with all their entitlement. Not the entitlement a government provides, but the kind history bestows.

Just what that entitlement entails arouses in young Margo a wellspring of questions. (We are talking, after all, about a professional journalist’s education.)

“Are we rich?” she asks her mother after a schoolmate’s assertion of her presumed wealth yields both flattery and shame. Mother raises her impeccably groomed eyebrows with disdain before giving her daughter “general instruction in the liturgies of race and class” by insisting, “We’re considered upper-class Negroes and upper-middle-class Americans. But most people would like to consider us Just More Negroes.” “Do we have Indian blood?” she asks her mother after summer camp. “Some,” Mother acknowledges, weary with what her daughter notes is the “slightly pathetic need,” shared by blacks and whites, to believe they have Native American kinship. Soon, Margo will learn about “passing” for white—something her immediate family never considered doing, though it was carried out even by those inhabiting the charmed circle of upper-class blackness. She mentions a cousin who “looked as if her portrait could hang in the Museum of the Confederacy” and “chose to live as a fair-skinned Negro, passing for convenience when she wanted to patronize white-only shops and restaurants.” She also mentions her great-uncle Lucious deciding after decades of working as a traveling salesman to “stop being white” and return to Negroland. On the one hand, young Margo is excited by this familial idiosyncrasy. “I knew something none of my white school friends knew. It wasn’t just that some of us were as good as them, even when they didn’t know it. Some of us were them.” And yet her parents “looked down on [Lucious] a little. Not because he’d passed, but because he’d risen no higher than traveling salesman. If you were going to take the trouble to be white, you were supposed to do better than you could have done as a Negro.” Our ongoing, so-called National Discourse on Race rarely manages to accommodate such complexities, except when, say, someone like critic Anatole Broyard is posthumously “outed” as a Negro, or when somebody bothers remembering, as Jefferson does in this book, that Nella Larsen, who explored such phenomena in her 1929 novel Passing, is a valuable (and undervalued) African American writer.

Maybe, Jefferson suggests, there was yet another collective identity to which her family and others living in Negroland belonged: that of a “Third Race, poised between the masses of Negroes and all classes of Caucasians . . . possess[ing] a wisdom, intuition, and enlightened knowledge the other two races lacked.”

Plenty of time to figure all this out. In the meantime, there are elite schools to attend, TV shows to watch (where the family greets the rare appearance of black performers in the ’50s with special, not always flattering scrutiny), written words to consume. Young Margo is especially enthralled by the Ebony magazines in the family den: “Wonder Books of sociology,” she describes these glossy exemplars of the “Negro press,” as they commemorate black uplift, display black glamour, inspire black self-inquiry, tabulate black losses and gains in the social arena. The things that happen inside Margo’s head are given comparable importance in this book to the things that happen to her and her family in Jim Crow’s waning days: a summer trip to Atlantic City ruined by an unexplained change in accommodation; the insensitivity shown by a white teacher when teaching Margo’s fourth-grade class a Stephen Foster song featuring the word darky, unexpurgated. At each such turn, her family is on the case, encouraging Margo to recognize the slights and signs of prejudice and to reinforce her racial pride. She joins a chapter of Jack and Jill, the national organization “founded by mothers to ensure that their children embody and perpetuate the values of the Negro elite” and, by the way, to “guarantee that our social lives do not depend on the favor of white schoolmates and their parents.”

Such collective self-sufficiency, at whatever social strata, would likely find a supporter in Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose own passage to self-realization, as chronicled in both Between the World and Me, his widely hailed letter to his fourteen-year-old son, and his 2008 memoir, The Beautiful Struggle, was as intellectually charged as Jefferson’s, if far more perilous. By the early ’90s, when Jefferson had all but sealed her credentials in the New York media’s upper tier, Coates was going to schools in forbidding, high-risk circumstances, specifically the inner city of West Baltimore, where, as Coates tells his son, “the only people I knew were black, and all of them were powerfully, adamantly, dangerously afraid. I had seen this fear all my young life, though I had not always recognized it as such.”

In such an environment, where survival was the more urgent imperative than enlightenment, Coates, though as avid for knowledge about the world as Jefferson, attended urban schools that “were not concerned with curiosity. They were concerned with compliance.” Coates’s family compensated for most of what the schools failed to provide, especially passion and respect for the written word; his mother encouraged him to write about whatever bad things happened to him in school, while his father, a former Black Panther, instilled in him a passion for books by black writers and thinkers. His father also applied harsh discipline, often with his belt, intending to help inoculate his son against the impulse to greater violence. “Either I can beat him, or the police,” Coates recalls his father saying in defense of corporal punishment. “Maybe that saved me. Maybe it didn’t. All I know is, the violence rose from the fear like smoke from a fire, and I cannot say whether that violence, even administered in fear and love, sounded the alarm or choked us at the exit.”

Though Jefferson never uses such severe terms to characterize her parents’ efforts to give her the personal autonomy to deal with the white world, it’s tempting to wonder whether there was a kind of fear implicit in Negroland’s demands that its children be not just as good as but better than Caucasians—a fear complete with unintended long-term consequences. By the time the reader reaches Margo’s high-school years, the self-criticism has become more pronounced, the aspirations more inchoate, even desperate: “Wherever I was, whatever I did, I wanted to be popular. I was considered talented; I was inclined to be intellectual. I valued both.” The years to come, in college and beyond, make up a chronicle—complete with hypertextual references to Louisa May Alcott, Adrienne Kennedy, and Charlotte Hawkins Brown, “the doyenne of Negro manners”—of Jefferson establishing a personality that can confidently stand apart from anybody’s attempt to restrict, or contain, her identity and, thus, her possibilities as a writer and a woman. Somewhere along the way, she will “actively cultivate a desire to kill myself,” a wish from which she eventually extracts herself with the realization that “unrequited death is as futile as unrequited love.”

Yet Coates’s book and Jefferson’s overlap most chillingly in the knowledge of a certain kind of death awaiting African Americans seeking release from the constricting demands of Difference. “In Negroland boys learned early how to die,” Jefferson writes, opening a chapter that addresses the varied ways, including suicide, that even black youths in gilded surroundings can become statistics. One of the larger narratives weaving through Coates’s letter concerns a popular and charismatic Howard University classmate named Prince Carmen Jones, who had been driving to see his fiancée when he was shot to death by an undercover policeman from Prince George’s County, Maryland, in a case of mistaken identity. (The officer, as Coates writes, “was charged with nothing. He was punished by no one. He was returned to his work.”) Embittered by this case, and by the many similar incidents before and since in which black people have been killed as a result of excessive force, Coates apologizes to his son for not being able to altogether protect him from similar outcomes, though he adds: “Part of me thinks that your very vulnerability brings you closer to the meaning of life, just as for others, the quest to believe oneself white divides them from it.”

Though these books speak for different generations, their convergences sting. It often appears that the legally sanctioned racism ebbing away during Jefferson’s childhood has somehow persisted even without such sanction, and that it has become more immovable than ever. What was characterized as “The Veil” of race hatred in W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1903 The Souls of Black Folk (still the ur-text for books such as these) keeps tangling up our forward momentum. So these stories will still need telling, their pleas for recognition will remain pertinent. The world needs reminding—and not just Caucasians—that there are as many ways to deal with Difference and its discontents as there are ways to keep death at bay. You may not be able to escape the irrational fears of those who insist on misunderstanding you. And you may not achieve the perks and sweet insulation that come with membership in the aristocracy. But listen to what Coates advises his son, more in resignation than in sorrow: “You have to make your peace with the chaos, but you cannot lie.” And then listen to Jefferson’s spicy variation on Du Bois’s concept of black America’s “double-consciousness”: “Being an Other, in America, teaches you to imagine what can’t imagine you.” Taken together, these sentiments mark the beginning of a path toward a now-unimaginable future. Start from that point, and you may eventually find the most valuable possession of all: a hard, true self.

Gene Seymour has written about music, film, and literature for such publications as The Nation, the Los Angeles Times, Film Comment, and American History. He lives in Philadelphia and is working on a collection of essays.