A Lebanese pharmacist concocts a mysterious green potion that makes him sexually irresistible to his female customers. An architect dreams all day of emigration while playing a computer game simulating the demolition of downtown Beirut. A son rescues his father’s favorite prostitute, a woman who ruined his childhood but also made him a man, from a brothel that is about to be bombed. He looks after her for the rest of her life. An eccentric old man in the port city of Tripoli claims to be the last living descendant of the Frankish invaders who led the Crusades. He applies for a French passport but is swiftly rejected. The Franks were not French, a consular official tells him. “I, my boy, am the last witness,” the old man says to a young doctor who pays him a visit. “The meaninglessness of history is engraved on my forehead.”

As a teller of tales and a spinner of stories, the Lebanese author Elias Khoury is on fire in his latest work of fiction, the novel Broken Mirrors: Sinalcol, published in Arabic in 2012 and now translated into English. The book is set in an ambiguous time, at the end of 1989 and the beginning of 1990. Lebanon’s fifteen-year-long, multi-factional civil war is winding down. The Taif Agreement has just been signed, calling for an end to the fighting, a return to normalcy, and parity between Christians and Muslims in parliament. Plans for the massive, controversial reconstruction of Beirut’s city center are already well under way. And yet, shelling still occasionally lights the nighttime sky, and one of the worst episodes of the civil war—involving rival governments, gruesome fighting among Christian groups, and a brutal Syrian intervention—looms on the horizon, moving in like a malevolent storm.

Into this maelstrom steps Khoury’s narrator and protagonist, a dermatologist named Karim Shammas, who is stumbling toward his own personal crisis. He has just returned to Beirut after ten years of self-imposed exile in France, where he left his wife and two young daughters to worry and wonder what his deal is; all he has told them is that an ache in his soul has sent him home. In Lebanon, Karim gets hopelessly tangled up in the stories of his brother, his father, his former girlfriend, and the old friends with whom he fought, briefly, on the side of the Palestinian fedayeen. He also sets himself on a dubious search for the enigmatic Sinalcol, the nom de guerre of an alleged thief who terrorized the population of Tripoli during an early phase of the civil war.

Khoury gives each of his characters, major and minor, a web of background material, including tragedies, traumas, love stories, family dramas, crises of faith, dreams, nightmares, dogged rumors, outright lies, and fanciful anecdotes that sound like legends and fairy tales. Like catching up with a brilliant but garrulous friend, this creates the effect of a narrative that is constantly digressing from and returning to its main subject, with each excursion bringing back some curious detail or subtle elucidation. Though occasionally delirious, the pattern of Khoury’s tangential storytelling also feels well planned, as if he were quietly and deliberately building an argument about the capacity of art (vernacular, conversational, literary) to beat back the sense that history is meaningless, repeating itself dumbly.

Some of the stories are drawn from real events: Maroun Baghdadi, the prominent filmmaker and chronicler of Lebanon’s civil war, falls to his death after stepping into an empty elevator shaft amid suspicious circumstances. Khalil Hawi, a poet widely considered a national treasure, kills himself on the eve of the Israeli invasion. Other story lines, while fictional, ring true to the life of the city in that time: A beautiful student named Jamal leads a daring attack in Israel, arriving by stealth, hijacking buses, and facing the army head on. She is killed in the ensuing skirmish, the story headline news until the leaders of her movement are also killed and Jamal is forgotten. A humble baker in the northern district of Akkar, Yahya Nabulsi, launches an audacious Marxist insurrection against the feudal families in the area. When he dies in prison, his nephew marries his widow and revives his revolution—but he sets aside its origins as a peasant uprising and turns it into a conservative Islamist movement instead.

Karim meets Baghdadi and recites Hawi’s poetry. But he falls in love with Jamal and briefly signs on to Nabulsi’s cause—which is how he ends up in possession of both their personal papers. Ten years after fleeing a war that had become absurd, capricious, exhausted, and confused, he is still the trustee of their writings, the keeper of their stories, and the archivist of their most dangerous ideas. Six months after returning home, falling in love with three women, and losing virtually every chance he has for a stable future, Karim realizes those old papers could still get him killed.

In general, if you want to tell the story of a civil war, then narrowing the narrative scope to a single family is a good way to begin. Nothing represents the breakdown of a state better than the story of two or more siblings who are torn apart or pitted against one another. This is all the more true if the conflict in question is occurring in the latter half of the twentieth century and grossly complicated by colonialism or the Cold War. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun delves into the Biafran War by following the opposing fates of twin sisters. Anthony Marra’s A Constellation of Vital Phenomena likewise captures the horrors of war in Chechnya through the story of a doctor and her sister, who disappears in a maze of drugs and human trafficking. Orhan Pamuk’s Silent House uses a broad generational canvas—three siblings, a family secret, and the boy who shared their childhood—to depict a critical moment in Turkey’s history, when boomerang coups and the division between communists and nationalists threatened to pull the country apart.

Khoury’s Broken Mirrors is easily as allegorical. Karim and his brother Nasim call themselves twins, although they are actually brothers born less than a year apart. Karim is the clever one, and as the war in Lebanon begins, he drifts to the Left and joins a group aligned with the Palestinian resistance. Nasim never applied himself at school—his brother always took his tests for him—and so, being a bit dumb, he drifts to the Right and falls in with one of the main Christian militias. He also makes a small fortune as a smuggler and war profiteer, building an empire from trade in drugs and construction materials. And when his brother leaves for France, he marries the girlfriend Karim leaves behind. The girlfriend, Hend, is at first too stunned to realize how very different they are, or what a grave mistake she has made. Nasim lures his brother back to Lebanon with the promise that they will build a hospital together. When a cargo ship packed with goods explodes in the port of Beirut, the hospital idea is finished, and Karim, having signed over all his rights to land, home, and inheritance, is left with no ties, nothing to recuperate, and no hope at all. After years of resentment, is this not what Nasim has wanted all along?

In addition to being a novelist and a playwright, Khoury is one of the few writers in the Arab world who still lives out the role of public intellectual (so many of his predecessors and contemporaries throughout the region have been sidelined, imprisoned, or killed, and the absence of a more robust community of critical thinkers with daring imaginations has been palpable in the failures of the Arab Spring). For years, Khoury edited Al-Mulhaq, the influential supplement of the Arabic newspaper An-Nahar. He was the artistic director of an avant-garde art space, Theatre de Beyrouth. He has been a teacher of university students, a regular commentator on Lebanese political affairs, and a critical source of inspiration for a challenging generation of artists including Rabih Mroué, Lina Saneh, and Walid Sadek. He was also, rather famously, a fighter (with Fatah), an activist, and a founder of the Democratic Left, a once-hopeful political movement that tried to pick up some of the more crucial attributes of the local communist party (pushing for secularism, political diversity, and a real transition to democracy) and then quickly faltered with the assassination, in 2005, of another founder, the charismatic writer Samir Kassir (see above on the marginalization and elimination of intellectuals).

As such, Khoury has consistently woven an admirable political program into his fiction, starting with the shorter, more experimental novels such as Little Mountain, City Gates, and The Kingdom of Strangers, and continuing in the more elaborate, maximalist fictions White Masks and Gate of the Sun. A major part of that program, and a reason why the civil war persists as a subject in all his books, is Khoury’s idea that the civil war never really ended, and that Lebanon has been in a state of open conflict for a hundred and fifty years. As he once told an interviewer: “The war was a very important school for me. During war everything is timeless: you live the present, the past, and future in the same second; you live and die in the same second; you are everywhere and nowhere in the same second. This is very special. . . . We lost many friends, our youth, and many other things; but we didn’t lose a subject.”

What Khoury’s novels have gained, in the meantime, is the richness of a literary past that extends further back and further afield. The basic plotline of Broken Mirrors may focus on a sibling rivalry, which makes it possible to understand the complexities of the civil war through the story of one family. But the fact that the novel is so full of other stories—ranging from fanciful and folkloric to wonderful and strange to rueful, ironic, and droll—suggests the resurgence of an older, fuller heritage that is capable of assimilating and subsuming the war narrative, while also adding to it different layers of meaning. The classic judgment on civil wars, especially in the developing world, is that they are fueled by ethnic hatreds that are ancient and therefore inevitable, impossible to resolve. The countervailing effect of Khoury’s novel is to show how an entire world of literary forms—from pre-Islamic poetry to proverbs, oral storytelling traditions, and the tales within tales of A Thousand and One Nights—may be the more meaningful ancient phenomenon that returns, like overgrowth in a ruin, to heal and regenerate the culture of a badly damaged place.

Toward the end of the book, as Karim starts to fall apart, he also begins to discover a great many subtle fought truths: that everyone, no matter who they fought for in the war, should have the “right to take control of their past,” that everyone has a “story with [their] own story,” and that the secret of Beirut “was that the city was made up of mirrors, and that the individual was not one but an assemblage of individuals who had made out of their misery mirrors for their souls.” Like all of the characters he encounters, Karim comes to carry so many different stories that he is buried in the end. This is tragic, of course, but it also comes as a kind of relief—as if Karim, in submitting to the force of the war, has become a part of its story, and a part of Beirut. All those broken mirrors and fractured stories seem not chaotic or confusing but rather strangely hopeful, as if they could one day add up to a place where people who have hated and killed one another might find that they can live together, through a war, by folding it into the stories that came before and will continue to be told after.

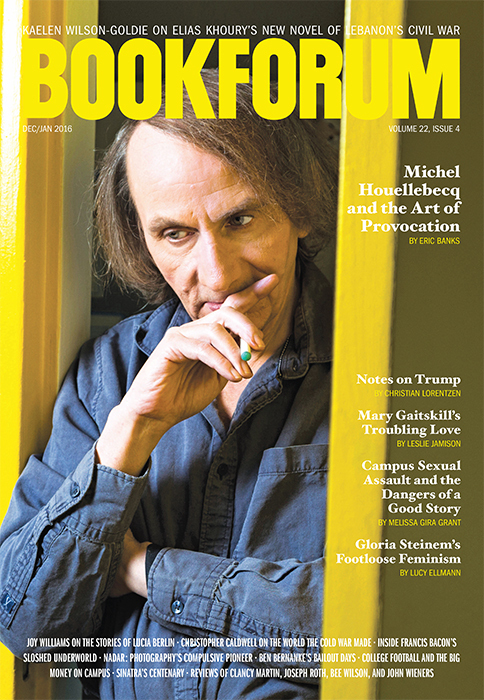

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer and critic based in Beirut.