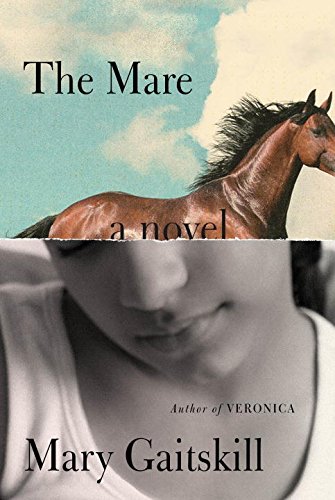

In immediately palpable ways, Mary Gaitskill’s new novel, The Mare, feels far away from the risqué terrain she’s famous for illuminating. There’s no arrogant john pushing a teenage girl’s mouth onto his dick in a cramped car, no lawyer bending his secretary over his desk to spank her for typos, no model’s apartment in Paris with marzipan in the pantry and clap shots in the fridge. At first glance, The Mare seems to have traded the sordid for the bucolic, abandoned Bosch for Rockwell: We get bike rides down country roads, horses galloping across open fields, county fairs full of festive pastel tents, neatly quartered ham-and-cheese sandwiches made “with tomatoes for health.” The narrative charts the relationship between Velvet, an eleven-year-old Dominican-American girl from Brooklyn, and Ginger, the middle-aged white artist who gets involved in her life through the Fresh Air Fund, a nonprofit that sends underprivileged kids to spend summers with more “privileged” hosts. The brochure version of their bond emerges as “a blur of summer sights and smells . . . the manure of the horse barn, barbecue sauce, the roller coaster at the Dutchess County Fair, her hair in my mouth . . . the pink and yellow shacks of the flimsy fairway.”

But Gaitskill quickly troubles that blur. The bond that forms between Velvet and Ginger is not the stuff of after-school specials; it reckons powerfully with the tension generated by a caregiving relationship that isn’t supported by convention or biology. In its fidelity to the fraught architecture of intimacy—its belief that pain and attachment are impossible to disentangle—the novel plugs into the same electric honesty that has charged Gaitskill’s work from the start. Ginger feels an overpowering desire to care for Velvet—an immediate impulse, when they first meet, to touch her face—but is also deeply aware of their bond as one without category. She feels the stress of mothering without being a mother: “Being this kind of adult was like driving a car without brakes at night around hairpin turns,” Ginger thinks. “My body tensed and relaxed constantly. . . . I couldn’t sleep.” Velvet’s mother, Silvia, says: “She’s got no kids and has to borrow somebody else’s.” Ginger’s husband’s ex-wife calls it “an easy way to play at being a parent.” But it’s not easy at all. Ginger admits to herself, after decades of sobriety: “I wanted to drink—really wanted to, for the first time in years.”

Velvet’s presence turns Ginger’s orderly home into “something alive and full of goodness,” and ultimately it’s this “something alive”—the fraught intensity of caring for another person—that exposes The Mare as a consummation of running themes in Gaitskill’s work rather than a departure from them. After reading it, I reread all five of her previous books, and it was like drinking contrast fluid before a CT scan; obsessions that had been running through the veins of her writing all along became suddenly visible—specifically, a fascination with unconventional forms of caregiving. This fascination has shown up before, in furtive glimpses: In “Because They Wanted To,” a teenage runaway takes care of three young kids when their mother doesn’t come home one night; in Veronica, an aging model nurses her friend—a caustic office temp—through late-stage AIDS; “Don’t Cry” tracks an American woman accompanying her friend to Ethiopia to adopt a toddler. A fixation on unexpected forms of caregiving has run like a subterranean river through Gaitskill’s work, revealed in slivers of visibility, and here—in The Mare—it finally surges fully over the narrative terrain.

Gaitskill’s most explicitly autobiographical examination of caregiving is a 2009 essay called “Lost Cat,” which recounts her relationship to a stray feral kitten alongside her own experiences with several children through the Fresh Air Fund. Gaitskill fears that she has made the kitten more vulnerable by caring for him—“by exposing him to human love I had awakened in him a love that was unnatural and perhaps too big for him”—and worries more generally about the potential harm lodged in any act of love:

I have loved people; I have loved children. And it seems that what happened between me and the children I chose to love was a version of what I was afraid would happen to the kitten. Human love is grossly flawed, and even when it isn’t, people routinely misunderstand it, reject it, use it or manipulate it.

She insists on her love—“I have loved children”—but also interrogates it. Exploring nontraditional and nonbiological caregiving relationships—strangers caring for strangers, friends caring for friends, humans caring for animals—allows Gaitskill to unsettle any sense of love as an easy or spontaneous given, an uncomplicated imperative; she figures it as something forged instead, something to be grasped and built. These unconventional relationships coax out certain uncomfortable tensions native to love more broadly: its contingency and its intentionality; its self-serving dimensions and the price of its partial bestowal—the damage of trying to fulfill needs that can’t be wholly satisfied.

Gaitskill has often been pegged as a scribe of deviance, depravity, and disconnection, though her nuanced candor has always felt—to me—less like cynicism and more like an acknowledgment of the messiness of emotion. In The Mare, her vision finds a new theater, but its core remains the same: to show how we hurt each other with or without intention, how pain and intimacy get their wires crossed.

Ginger’s gestures of care often trail harm in their wake. She takes Velvet to a fancy store to buy her an outfit for her birthday, and the outfit ends up making trouble back home, when other girls at a party beat her up. Even though Velvet claims the outfit wasn’t the reason—“She said the clothes made them respect her”—it’s also clear that it signified money, and that its residue invited their anger. Ginger’s gift held that damage. “Leave the girl alone,” her husband tells her. “What do you want to do, get her hurt worse?”

If cruelty was marbled with odd veins of intimacy in Gaitskill’s early stories, then intimacy carries some measure of unintended cruelty here. Part of what feels so singular and powerful about Gaitskill’s method is that she refuses to resolve the aftermath—of an exchange or an encounter or a gesture—into a stable, undivided note of connection or rupture, gift or curse. Velvet’s new skirt holds the residue of Ginger’s good intentions; it holds the girls who beat her and the care of the mother who cleaned her cuts; it holds this mother’s offense at the fact of the gift itself: “like the woman was saying to me, What’s wrong with you, you can’t even dress your child right?” We get the gift and its aftermath from multiple perspectives: not only from Velvet and Ginger, but also from Silvia and Ginger’s husband, Paul. The novel alternates between these four voices—with Velvet’s and Ginger’s granted the most space—and Gaitskill’s allegiance to nuance and contradiction finds a graceful vessel in this structural alternation: The perspectives clash and complicate; they also save the characters from archetypal simplicity.

Over and over again, we see the ways that Ginger’s presence becomes an absence—the more care she gives, the more its limits sharpen into focus. One night back in Brooklyn, after Velvet’s mother has shoved her against a wall, grabbed her throat, pushed her, and pinned her to the floor—“I’ll put you back down until you stay there,” she says—Velvet pulls out a doll, a precious object that makes her think of Ginger: “She’s nice but she’s. . . . I couldn’t think what she was, except that she wasn’t here.” By refusing to inhabit only the white middle-aged female perspective (which would have been the safer but less interesting choice for a white middle-aged female author), the novel forces us to dwell inside the negative spaces Ginger creates when she’s not there. We are with Velvet when she gets shoved against the wall, even if Ginger isn’t. These negative spaces haunt the moments of tenderness between Ginger and Velvet without invalidating them.

These moments of tenderness—moments that might look saccharine out of context—hold plenty of tension coiled inside them. One night Velvet and Ginger go driving “into fog and everything got weird-beautiful,” and when Velvet asks, “Can we get a little bit lost?” Ginger says, “Honey, we already are a little bit lost,” and then says, “Not really. Because we’re together.” It’s a moment that could easily have been cloying, but it’s complicated by its troubling context: They are driving home after a dinner where Ginger relapsed for the first time in years. She’s a little bit drunk, and she’s asked Velvet not to tell anyone. “Yes, the drink was a mistake,” Ginger thinks, “but a healing one. Our beautiful time in the car; a moment of forgiveness; a way to the in-between place. The drink helped me to get there.” The drink helped her get there; but a moment later, she bends over the toilet and makes herself throw it up.

It’s this “in-between place” that grants the narrative its stubborn complexity; this space that holds transgression and forgiveness, deep longing alongside the bruise of its partial satisfaction. It’s the same sensitivity to the “in-between place” that yielded Gaitskill’s description of another woman—in another story—as possessing “strength like the steel-structure of a bombed-out building.” In this bombed-out building of a woman, damage lingers, but it also offers contours. In The Mare, a relapse bestows shame and mercy at once. With its multiple perspectives, the novel doesn’t just describe the in-between place, it actually lives in it: One girl’s gift is another girl’s punching bag; one woman’s care is another woman’s betrayal.

At the center of The Mare is a mare: a temperamental horse named Fugly Girl whom Velvet renames Fiery Girl, a phrase Ginger has used to describe Velvet. During her visits upstate, Velvet rides Fiery Girl and cares for her—and, in one sense, they are parallel figures, both mistreated and skittish. But the horse also allows Velvet to take on the role of caregiver, to be something other than the objectof care from others. The first time Velvet really tries to control Fiery Girl, she feels her mother rising up inside her—“Fiery Girl yanked me and I yanked her, and my mom reached out of me with her fist, she grabbed the rope”—but she also intuits the importance of trust, using her legs to tell the horses she rides: “It’s okay, you’re okay.” There are no easy morals here: Velvet has been wounded by her mother’s force, but she also feels some version of that force within her, and it becomes part of her connection to Fiery Girl, rather than something she simply overcomes. She still holds her mother inside her, a woman who has told her: “I will knock you down until you don’t get up.” And even though she gets up, over and over again, she rises with her mother’s voice still echoing in her mouth, her mother’s pulse still beating through her veins.

The novel culminates in a riding competition that Velvet’s mother has come up to watch, despite her fierce early opposition to Velvet’s learning to ride. Ginger is there as well, and she witnesses a moment of ecstatic connection between girl and horse: “The quivering rose into her eyes, but it did not look weak; her emotion was triumph with its wings open, showing its heart.” But this moment of swelling joy is not the pat, slick victory of an underprivileged girl finding “triumph with its wings open” on her horse; it’s complicated by the pained terms of its joint custody: After Ginger witnesses Velvet’s rapture, she feels “a second of bitterness that Silvia must be the one to hold this heart.” Gaitskill’s brilliance dwells in her refusal to resolve the moment into triumph or tragedy. Joy isn’t undermined by its muddling—it’s granted density and grit instead, permitted the dignity of its own implications.

One of the main critiques of sentimentality is that it forces overly simple narratives, but the crusade against sentimentality has become one of our simplest narratives of all: too much feeling, earned too easily. Gaitskill herself has often been co-opted into this war against treacle. If sentimentality is snake poison, then she’s been held up as its antivenom, our salvation from the saccharine, an ice queen on the cross to save us all. The New York Times Book Review proclaimed Bad Behavior “utterly unsentimental” back in 1988, and “unsentimental” has been used by critics to describe every one of her books since. She’s also been called detached, sadistic, sarcastic, and brutal—one critic even likened her syntax to a “dental drill”—but I’m particularly interested in how her work has been made a mascot for the “unsentimental” in a more positive sense: what this term is meant to praise, and what this praise might ignore.

One knee-jerk understanding of “unsentimental” writing assumes that emotion has been left implicit, exiled to the wide margins of so-called minimalist prose: This vision of the “unsentimental” respects the decorum and subtlety of not spelling it out, “it”being feeling itself. Or else “unsentimental” gets yoked to a sense of detached objectivity, or an insistence on the brutality of human feeling as opposed to an embarrassingly naive faith in its saving possibilities.

But Gaitskill’s prose has never been cold, that’s only what it’s been called; and her writing has never been about the absence of emotion so much as its unapologetic abundance. She resists sentimentality not by banishing feeling to the white margins with understatement but by granting emotion enough space to misbehave. There’s a tonal democracy in her portrayals that reads, to me, less like dissection or dental drilling and more like the honoring of simultaneity and mess, the precise mapping of spillage. If Gaitskill is “unsentimental,” then her writing does nothing so much as show why that word is a terrible one: a cynical term that suggests fear and evasion more than any kind of genuine attempt to grapple fully with what we feel.

This is what’s so brave about The Mare—the way it does believe in the mess of connection, and does attempt its ragged portrait, rather than simply outlining the crystalline loneliness of disconnection. It dares us to find it sentimental—squatting inside the prefab frame of an easy redemption story—but ultimately resists sentimentality with a powerful insistence on the vexed complexities of sentiment. We watch people with good intentions trying to be good to each other and harming each other anyway. Their care is sullied, their damage unintentional. They love each other with the strength of bombed-out buildings, and give each other only what they can.

Leslie Jamison’s most recent book is The Empathy Exams (Graywolf, 2014).