A musician’s centenary celebration typically offers a chance to revisit songs long departed from the charts and to recall mostly forgotten triumphs. But that’s hardly the case with Frank Sinatra. I recently checked, and saw that the ten best-selling jazz songs on iTunes include four by Sinatra. And the top-selling jazz album today is a collection of Sinatra tracks for the Reprise label, most of them around a half-century old.

Face it, the Chairman of the Board hasn’t gone anywhere. He’s still where he’s always been: A-number-one, top of the list, king of the hill. David Lehman tells the story, in his aptly named appreciation Sinatra’s Century, of a senior corporate executive who strolled into a meeting with his management team. He slapped an eight-by-ten glossy photo of Frank Sinatra on the table and announced to the room: “This guy has been dead sixteen years and he still makes more money a year than all of us combined.”

Pretty good for a centenarian, no? Indeed, Sinatra’s more like a centurion, those hardy Roman soldiers who conquered the world. And the high rollers knew that, even when Sinatra was alive and kicking. Caesars Palace announced the singer’s appearances in the ’70s with a medallion that proclaimed: “Hail Sinatra, the Noblest Roman.” When even Caesar offers tribute, who are the rest of us to disagree?

Of course, a centenary celebration demands new books on Sinatra, even though there’s no shortage of commentary on him. The first book about the singer came out in 1947, when Sinatra was only thirty-one years old. By now, the literature is expansive and finely segmented. If you want to know about his musicianship, check out Will Friedwald’s Sinatra! The Song Is You (1995). If you prefer Sinatra the screen star, go to David Wills’s forthcoming The Cinematic Legacy of Frank Sinatra. If you’re hungry for gossip, Kitty Kelley’s unauthorized 1986 bio, His Way, dishes it out in huge helpings. Or if you just want a starry-eyed fan’s appreciation, Pete Hamill’s Why Sinatra Matters (1998) is the book for you.

The singer’s death in 1998 did not slow down the endless flow of new material. You can now check out Sinatra’s FBI files—1,275 pages, released in 1998—and get the inside scoop on his underworld connections. The artist’s valet and confidant George Jacobs shared all his secrets in the 2003 tell-all Mr. S: My Life with Frank Sinatra. The last blockbuster addition to the literature came in 2013 with the publication of Ava Gardner: The Secret Conversations. Sinatra once recorded a song called “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone.” Did he have a hunch that so many former associates would break the code of omertà?

What author would even try to top all this? Yet here in 2015, James Kaplan follows up his massive 2010 book Frank: The Voice with an even longer book, this one a look at mid- and late-period Sinatra. This new work, Sinatra: The Chairman, starts in 1954, in the aftermath of the singer’s huge success on the screen in From Here to Eternity, and devotes nine hundred pages to the remaining forty-four years of Sinatra’s life.

I was apprehensive when confronted with the book’s sheer size. Could Kaplan really hold my attention for so many pages? These facts have been raked over so many times already. Wouldn’t I be tired of Sinatra long before I reached the finish line?

I’m happy to report that my misgivings were unfounded. Kaplan’s new Sinatra book is a joy to read. His skill as a storyteller shines through on every page—which is perhaps not surprising for an author who learned his craft as a fiction writer under the mentorship of New Yorker editor William Maxwell. You won’t find many new revelations in these pages, and Kaplan is often too indulgent in excusing the darker side of his subject’s character, but the reader seeking an in-depth account of Frank Sinatra’s life and times won’t find a more entertaining guide than this new biography.

In all fairness, Sinatra himself deserves much of the credit for the allure of this narrative. Did anyone in the twentieth century have a more interesting and wide-ranging life, or a more intriguing roster of associates? Here’s a sample list of the friends of Frank who fill up his bio: John F. Kennedy, Lucky Luciano, Humphrey Bogart, Judy Garland, Ronald Reagan, Marilyn Monroe, Lauren Bacall, Franklin Roosevelt, Grace Kelly, Dean Martin, Ava Gardner, Leonard Bernstein, Sammy Davis Jr., Duke Ellington, Sam Giancana, Antônio Carlos Jobim, Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, Cary Grant, and Richard Nixon. Even the bit players in the story are superstars in their own right.

This cast of characters is a storyteller’s dream, and Kaplan makes the most of it. On a few occasions, the book slows to a snail’s pace—during his account of the 1960 US presidential campaign, Kaplan makes unnecessary detours, getting caught up in an account of how Lyndon Johnson got chosen for vice president and a few other tangents that don’t have much connection to Sinatra. But these digressions are rare, and Sinatra: The Chairman tends to move forward with the smooth, inviting pacing of a Rat Pack casino show.

And what an amazing tale! Some people will tell you that the most gripping modern American saga is The Godfather. Well, with Sinatra’s bio, you get all of The Godfather (a story partly inspired by the singer’s own life) and lots more. Others might give precedence to Citizen Kane as the premier study of American ambition and success, but that story is also part of Sinatra’s—he battled with William Randolph Hearst and the publisher’s scribes for decades. And, if your taste tends toward nonfiction, a healthy share of the most memorable events of the past sixty years shows up in Sinatra’s bio: the Kennedy assassination, the space race (“Fly Me to the Moon” was NASA’s unofficial anthem), the civil-rights movement, the Reagan era, even the Ali-Frazier fight (Sinatra photographed it for Life magazine).

In Sinatra’s bio, you encounter the stories from Vegas that won’t stay in Vegas. You are treated to heaping helpings of DC tawdriness and scandal. You get plenty of glimpses behind Hollywood’s superficial glitz and glamour. You want sex, you get sex. You want violence, you get violence. And, lest we forget, some of the best music ever recorded during the twentieth century.

[[img]]

Kaplan is a fairly reliable guide to the Sinatra recordings. He wisely leans on (and amply acknowledges) Will Friedwald’s sagacity. Friedwald possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of mid-twentieth-century American popular singing and tends to make solid judgments on matters musical. Kaplan rarely deviates from Friedwald’s party line, but it’s a good party to join.

I carp a bit at Kaplan’s idolization of Nelson Riddle, the arranger on most of Sinatra’s finer tracks from the ’50s. Riddle was, no doubt, a master of his craft. But Sinatra also flourished amid even jazzier arrangements from Quincy Jones and Billy May. I admire Riddle’s charts, but I’m not the only jazz fan to wonder what Sinatra might have accomplished in the ’50s if he had pursued partnerships with, say, Marty Paich, Alec Wilder, Gil Evans, Billy Strayhorn, Bill Holman, Manny Albam, or other star arrangers of the period. Kaplan, for his part, treats every Sinatra project without Riddle as a kind of insult to the music world. Here, as at several other junctures in the book, he acts more like a wide-eyed fan than a judicious biographer.

But Kaplan more than compensates for his Riddle-mania by digging deeply into the inner world of these recordings. Like Sinatra himself, Kaplan recognizes the importance of the whole ancillary team of songwriters, session players, arrangers, conductors, and producers who contributed to these iconic tracks. Even if you think you know these songs intimately, you will gain a new appreciation of their artistry while reading this book.

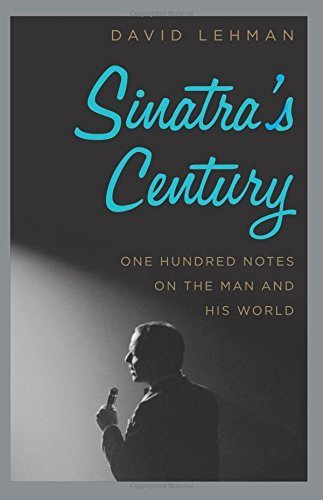

For readers seeking a more compact approach to Sinatra in his hundredth year, David Lehman provides the perfect alternative. His Sinatra’s Century is subtitled “One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World,” and that modest description conveys the quirky charm of this smaller volume. Lehman isn’t even writing chapters—just “notes.” Some of these observations are only a few sentences, while others run to several pages. He makes no attempt to follow a clear chronology or offer a comprehensive portrait of the artist, but he will hold your interest with his smart and passionate views. The book is the literary equivalent of a late-night session among Sinatra devotees sharing their favorite recordings over drinks, calling attention to the finer nuances of beloved tracks.

Even an old Sinatra fan like me learned new things from Lehman. I had no idea that Saddam Hussein was obsessed with Sinatra’s recording of “Strangers in the Night” (one of my least-favorites, by the way). Or that the vocalist never praised Riddle face to face. Or that both Miles Davis and Duke Ellington (as well as fifty-four other musicians surveyed by Leonard Feather) picked Sinatra as their favorite jazz singer. Or that Francis Ford Coppola offered Sinatra a role in The Godfather: Part III (but got turned down).

These books, in their distinctive approaches to their larger-than-life subject, are certain to gratify confirmed Sinatra fans. But I suspect that there’s a much greater Sinatra book still waiting to be written—a work that moves beyond the adulation of fans and starts to assess him with a larger dose of objectivity.

Kaplan, in particular, is far too reluctant to criticize his subject. He shares horrifying tales of Sinatra’s vengeance and violence but rarely gives him even the smallest slap on the wrist for his abusive behavior.

Let me give some examples. At one point, Sinatra sends a Hearst reporter an actual tombstone with her name engraved on it—OK, it’s not quite a severed horse head, but still it’s tantamount to a death threat, if you consider the singer’s associations. Kaplan merely points out that the writer was “being a prude and a scold,” although he admits that the articles in question were “factually accurate.” When another journalist criticizes Sinatra’s organized-crime connections, Kaplan suggests that this only represented bias against a person “whose named ended with a vowel.” Those who dare to tell the plain, unvarnished truth about Sinatra’s Mafia friends get accused of “ethnic contempt.”

As an Italian-American, I bristle at such notions. Does my ethnic pride really require me to refrain from criticizing thugs and killers? By the way, I can testify, based on my own family’s history back in Sicily, that the Mafia’s victims were almost always people of Italian descent. We aren’t doing any favors to the Italian-American community by glamorizing the crime bosses Sinatra courted and cajoled.

In a rare moment of insight on ethical matters, Kaplan recounts an anecdote about Mafia power broker Sam Giancana, a longtime Sinatra associate. Giancana complains to a friend about the singer’s hotheadedness. “If he’d only shut his damned mouth,” Giancana gripes, wondering aloud why Sinatra constantly picks fights with people who cross him and recounting how he always has to restrain the famous entertainer. “That a psychopathic killer had to tell Sinatra to curb his temper is a remarkable statement in itself,” Kaplan marvels—although, as usual, he stops short of condemning either party.

These are hardly the only Sinatra failings that get whitewashed in this volume. Kaplan admits that Sinatra’s affairs with underage women are “disturbing,” but then quickly adds that “a kind of amoral sense can be made of them.” When he hooked up with Diane McCue (who was, in Kaplan’s odd circumlocution, “just about, but not quite, fifteen” when Sinatra was fifty-two), the singer was suffering from his own emotional turmoil and needed, in our biographer’s words, “a kind of re-set with a fantasy virgin. It was a brand of consolation that his power could afford him.” Surely a candid observer ought to take a stronger stance than this.

Kaplan sums up his attitude in the midst of a discussion of a ’60s recording session: “Hearing him sing this way, you can forgive him everything.” But, as the case of Bill Cosby should remind us, consummate skill as an entertainer doesn’t give anyone a free pass as a human being.

Kaplan offers plenty of speculation about the Kennedy assassination, even hinting that Sinatra knew the real story behind the shooting. (“He knew things; he had been told things,” Kaplan teasingly asserts.) At the same time, though, Kaplan shows little curiosity about the case of Nevada deputy sheriff Richard Anderson, who had the misfortune to marry one of Sinatra’s old girlfriends and was later so provoked by the singer’s campaign against him that he punched Sinatra. Sinatra managed to have him suspended from the police force, and two weeks later Anderson was killed in a mysterious late-night hit-and-run accident. Kaplan serves up the bare facts of this strange case—how could he not include it?—but refuses to speculate on any connection between Sinatra and the violent death of his adversary.

The same is true of many other interludes in Kaplan’s book. We encounter numerous cases of Sinatra enemies getting threatened, intimidated, and beaten. But Kaplan’s response is to avoid value judgments or to offer up facile rationalizations like “Things frequently happened, and stories were told afterward, and the stories tended to pass through distorting lenses, bounce off mirrors, and turn strange corners.” I would have liked for our author to ask whether the uncritical adoration that Sinatra stirred in his audience isn’t the greatest of these “distorting lenses.”

I call out Kaplan for these blind spots, but he is representative of the whole legion of Sinatra apologists, who are so mired in their reveries of Rat Pack life that they lose all objectivity. Sinatra’s lapdog audience loved him all the more for breaking the rules everyone else was expected to follow. If a few people got beaten up, or worse, along the way, well (in the words of the Sinatra song): That’s life! Such an attitude may be acceptable for a fan, but it’s not for a biographer.

This glaring penchant to downplay Sinatra’s well-documented pattern of abusiveness, vendettas, and violent outbursts suggests that, even a full century after his birth, we’re still too caught up in the Sinatra image. We have yet to come to grips with the complicated reality of the man. Will we ever see him clearly and not as a projection of our own fantasies and aspirations? Maybe in another hundred years. Until then, the various accounts of Frank, for all their virtues, could use a little more frankness.

Ted Gioia writes on music, literature, and popular culture. His latest book is Love Songs: The Hidden History (2015), published by Oxford University Press.