Superficially, 2015 has been a banner year for Bill Bryson. After a long tour in development hell, the movie based on his 1998 book, A Walk in the Woods—his chronicle of a months-long trek, with an old friend, along the 2,100-mile Appalachian Trail—finally found its way into American theaters in September. The film sported an all-star, long-toothed cast, including Nick Nolte and Emma Thompson. Robert Redford played Bryson, who in real life looks like your bearded, bespectacled, kindly uncle. It received mixed reviews. Domestic box-office numbers were about where you’d expect a moderately successful middle-aged-hiking-buddy comedy to be these days—$28,425,479, as of this writing.

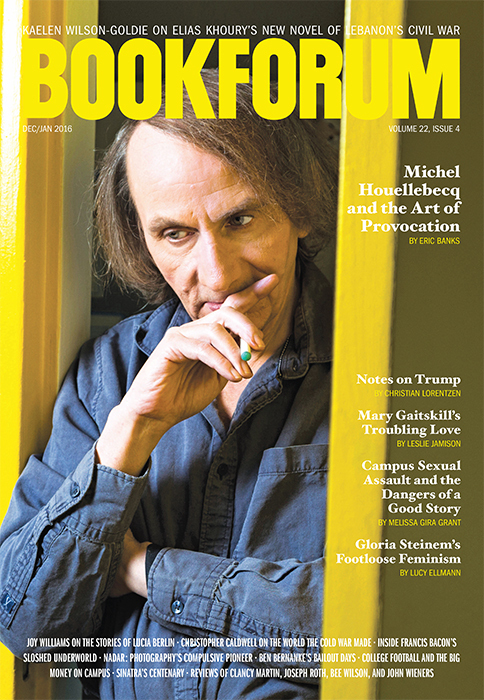

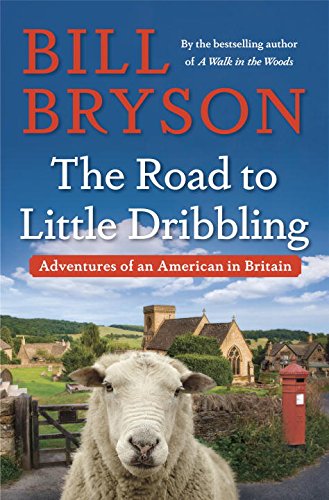

A month after A Walk in the Woods was released in the US, Bryson’s country of origin, The Road to Little Dribbling was released in the UK, where his wife and daughters claim citizenship and where he had recently taken the test to join them in legal Englishness. The book wasn’t really Bryson’s idea, he tells us in the introduction: His publisher pointed out that it had been twenty years since the publication of Notes from a Small Island, Bryson’s travel book about England. Though this record of his British travels wasn’t quite the hit that his Appalachian misadventure turned out to be, Bryson admits in one of his rare moments of un-self-effacing promotional zeal that the book “did awfully well there.” A Guardian editor went so far as to proclaim him an “adopted national treasure.” Now that he was becoming a citizen, wasn’t it about time for a follow-up?

The Road to Little Dribbling was a book whose time had come, in other words. But if inevitability were an assurance of artistic merit, then all movie sequels would be great and all made-for-campaign political bios unforgettable. The British press has largely tried to dress up the dullness of this latest British Baedeker by focusing on the few controversies that it courts. For example: Bryson spots a well-to-do woman in a café in the northern English town of Keswick giving a measly ten-pence tip on a twenty-pound tea (about fifteen cents on thirty dollars) and ponders the “quietly disgraceful” behavior of the British. The Independent called Bryson an “all-round good egg” and predictably cheered on his “(very polite) assault on British manners.” The Telegraph was more reserved in its judgment, asking if “middle-class women in smart jackets with short pockets reflect a growing incivility, or was that incident nothing more than the seemingly congenital British awkwardness about tipping?”

So Bryson comes out boldly for tipping, for London, for preserving the English countryside, and against the “Age of Austerity.” Perhaps this will be enough to endear him to social-democratic-ish readers in the UK, but what does it offer his considerable American audience? The historical vignettes are usually well rendered but forgettable. In 1935, George V, then on his deathbed, was told that he might soon recover and could return to the southern town of Bognor Regis for a vacation. “‘Bugger Bognor,’ the king reportedly said and thereupon died,” writes Bryson.

The author elects to go to Bognor, as the southernmost point of departure for his trek up to Scotland’s Cape Wrath, in protest of a wrong answer in a guide to the UK citizenship test. But the journey proves scarcely more interesting than the town’s bit part in the king’s dying. Bognor, it seems, used to have a long pier that people would jump off with dubious homemade flying contraptions. But most of the pier burned down, so the fearless inventors had to jump from the charred remains into the sand instead of the water, and that hurt. They got sick of that and moved the contest elsewhere. The castle where the former king once convalesced is no more. The town jeweler refuses to fix Bryson’s broken watch for less than thirty pounds and responds with “majestic indifference” to the plea “But I barely paid that for [it].”

The bus ride to the next town is disappointing—which in turn causes Bryson to pay extra attention to a British celebrity rag he finds in a nearby seat pocket. This sets him off, rather inexplicably, on a kids-these-days rant that reads like it could have come straight out of the most infamous chapter of Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind. “I found myself absorbed in the sumptuously mismanaged lives of minor celebrities whose common denominators appeared to be tiny brains, giant boobs, and a knack for entering into regrettable relationships,” Bryson writes. This prompts him to take a look at his fellow bus riders and sneer especially at “a young man with baggy pants and an insouciant slouch” who is “wearing a baseball cap several sizes too large for his head” with the word OBEY across the brow. “Earphones,” Bryson informs us, “were sending booming sound waves through the magnificent interstellar void of his cranium, on a journey to find the distant, arid mote that was his brain.”

One curse of well-known artists in any medium is that they will always be judged against the work that made them known in the first place, especially if a movie comes along just in time to highlight the contrast. As travel writing goes, The Road to Little Dribbling is not just a step back from, but many leagues behind, A Walk in the Woods. Bryson’s Appalachian saga had friendship, foibles, and an actual, very long trail to hike. In Dribbling, Bryson travels in scattershot fashion and often alone. To punctuate the action, he takes to complaining about the mental and physical diminishments of old age, trying to play his decline for laughs, but too hard. Reading along, sometimes you chuckle, and sometimes you cringe.

Jeremy Lott is a writer living in Washington State.