A generation gap divides readers of the New York Times. On one side, it’s the publisher of the Pentagon Papers, the first draft of history, the indispensable source. On the other side, the Pentagon Papers do not define the Times at all; failure to publish the Edward Snowden papers does. If you were a teenager on 9/11, the Times introduced itself to you with news of WMDs. A couple years later, it confirmed your ill impression by dousing the fuse on its own domestic-wiretapping story—ready to publish in the fall of 2004—until after Election Day, removing a major obstacle to George W. Bush’s second victory. Bill Keller, then the Times’s executive editor, later told 60 Minutes that the National Security Agency said he’d “have blood on [his] hands” if he published. It sounds credulous in retrospect, as though he let himself be flattered.

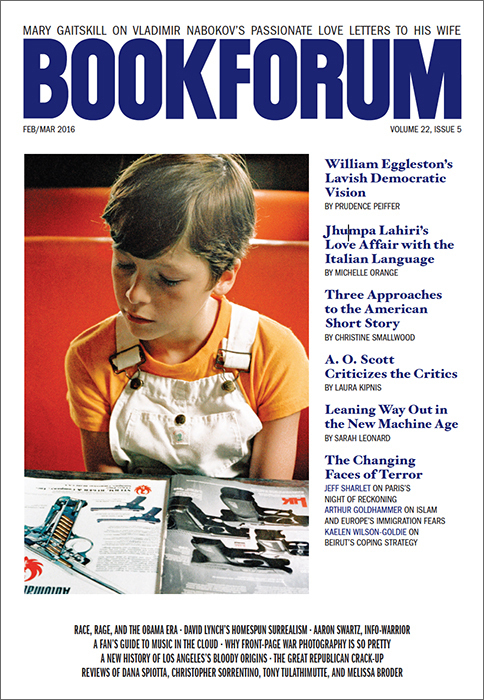

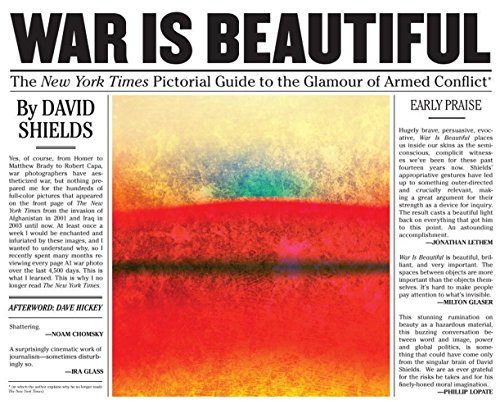

The Times, in short, has made itself an easy target for teardowns by the young and media-critical. But there is another kind of teardown that is not so much angry as sorrowful, tinged with betrayal and aggrievement, written by those who once loved and trusted the paper. David Shields’s War Is Beautiful is in this category. Putatively the story of why Shields “no longer reads The New York Times,” it is a coffee-table book containing color reproductions of front-page war photos taken between 2001 and 2014, mostly in Afghanistan and Iraq. In an introduction, Shields explains that though he read the paper “for decades,” the war photography from this period disgusted him. It obscured the reality of “death, destruction, and displacement.” It was too pretty and therefore false.

The pretty-false equivalence has long preoccupied Shields, who mistrusts the beauty of artifice. He reads, he has said, for “existential knowledge” and to access writers’ minds, and he’s impatient with ornaments like character and setting; The Great Gatsby, in his opinion, should be twenty pages long. Like an old-fashioned modernist, he rejects the old-fashioned. He believes in the progress of art and the obsolescence of past forms. He told Bret Easton Ellis in a recent interview: “I lack a pleasure principle.”

It’s interesting that someone so reality-savvy could be caught unawares by a publicly traded American newspaper, but Shields confesses that “nothing prepared” him for his study of these photographs. Nor is he the only one who was shocked. This book comes wrapped in twenty-three blurbs by some pretty smart people who sound like they’ve just seen a bomb go off. “Shattering,” says Noam Chomsky. “Shreds your soul in slo-mo,” says Andrei Codrescu. Others call it “a heart-stopper” and “disturbing” and “stunning.” This is the generation gap at work, I think. These guys hold the Times to a reputation that was earned a long time ago, and are disappointed when it falls short.

Shields makes his case formally. His first move is to shake the images out of chronological order and reorganize them by visual tropes. An Iraqi child huddling against an American’s waist goes in “Father,” along with Bush placing his palm on a soldier’s head. A brown man bending to kiss a white hand goes in “God.” In “Pietà,” we have images of the carrying of the dead: a man staggering away from an ambulance holding the body of a child, for example. In “Nature,” we have a camo helmet popping up above a field of poppies, a jeep on a palm-studded beach, and soldiers wrestling on their bunks. We also have two images we’ve seen many versions of during these wars: the orange glow of a flare held by a silhouette against the sky at dawn or dusk, and the silhouettes of tanks against the same. Out of context, the photos look like movie stills.

Death is shown gently, as bodies that appear asleep, or absently, in traces of blood. Iraqi soldiers lie on a red-dirt road while an American soldier walks away or a convoy passes. There are bloodstains in a hallway through which a mother and her children cautiously walk and streaks of blood on the front door of a white car. In that picture, our eye is drawn not to the car or the blood but to the huge-eyed kid, a boy of seven or eight, who stares toward us through the open (shot out?) windows. The caption informs us that two women were just killed here.

Shields files these two pictures in his “Beauty” chapter. Both the young boy and the woman in the hallway are presented, he writes, as “beauties seeking salvation.” They could be penitents in a Titian painting or refugees from a different continent. They could be anyone, Shields suggests, and this is the key to the book’s thesis. In an afterword, art critic Dave Hickey writes that “pictorial references preempt any hint of verisimilar-punch.” In other words, the boy and the woman in the hallway are archetypes, and their archetypal quality allows us to forget that they’re actually the specific casualties of a series of American foreign-policy decisions. The images are so anodyne, in fact, that they’re right at home in Shields’s inoffensive coffee-table book. Etc.

In appropriating front-page newspaper photos, Shields owes a debt to Sarah Charlesworth, the Pictures-generation artist who made her late 1970s “Modern History” series by rephotographing the front pages of newspapers with the text removed. Like Shields, Charlesworth, who died in 2013, was concerned with what else is in a news photograph besides news. Unlike Shields, she declined to make didactic arguments about mass visual culture. Shields, in War Is Beautiful, is always busy proving. And because he spends so much energy prosecuting what is really a slam-dunk case (that the Times shoots photos from an epic-heroic angle), he neglects to raise an obvious question: What would “real” war photographs look like?

The first time I saw an answer to that question was eight years ago, when I was in college, and a visiting Iraqi photographer showed a small group of us some pictures he’d taken from the early years of the invasion. He was unable to make them public, he explained, but after he left I went to my computer and took a few pages of notes. What distinguished these pictures was their explicit depiction of injury and death and their lack of shyness in cases where American soldiers were the self-evident cause. When Shields’s book reminded me of them, I wrote to the photographer to ask whether he could corroborate my notes, and whether he’d mind my naming him in print. Enough time had passed that he might even have published the images, I thought. His response was uneasy. The images were still private, he said. Further, “legal, privacy, and security concerns” compelled him to ask that I scrub identifying details of the incident (as I’ve done). The images are as toxic as they were in 2007.

One thing has changed, though: You can now see photos like them in huge quantities online. Blasted-open torsos, the fungus-like burns of white phosphorus—ten seconds on Tumblr return no shortage of horror. What’s less clear is whether Shields would wish the Times to run them. I have a feeling he would dislike such pictures. In interviews, he condemns war photos that are “pornographic.” He could fairly consider these victim porn. Then there’s the obvious point: A paper that ran these pictures wouldn’t sell. You cannot move a product that when used properly makes people nauseous at breakfast. Publishing real war photos is massively complex. The best evidence of that here is the fact that Shields made a book of appropriated images instead of the book of real war photos that would have been its negation.

The reasons some photos run and others don’t aren’t just ideological. They include everything from consumer appetite to US-government flattery and threats to the logic of photojournalists embedding with units, a relatively new practice that wasn’t at play in Vietnam. With embeds, a photographer’s safety depends on the same people he’s trying to document. In 2004, Stefan Zaklin, a photographer with the European Pressphoto Agency, was embedded with a unit in Fallujah and took a picture of an American soldier who had bled to death in a house. A unit captain saw it and threw him out. According to his LinkedIn profile, he is now a product-marketing manager for John Deere in Overland Park, Kansas. What makes his story complicated, though, is that it is unclear that “raw” or “real” war photographs, such as the one that got him ejected, are more effective antiwar tools than the sanitized versions Shields pillories. As I write this, the most important photograph in the world is of a long-limbed Turkish soldier bearing the body of a dead Syrian child from the Aegean Sea. Government leaders who wish for higher refugee quotas place this photo before their constituents—as they could not place a more gruesome image—and appeal to common humanity. Pietà.

Shields and Hickey would call this image archetypal. No verisimilar-punch. Too sentimental: untrue. In many ways they’re right. But if their argument is to compel us, we need to believe that it’s archetypal because of how it’s shot. We must concede that nothing is beautiful or horrible but the Times makes it so, a proposition that many soldiers say is false. War is gruesome and aesthetic. Speaking to a reporter in 2007, one sergeant called the invasion “a front seat to the greatest movie I’ve ever seen in my life.” Soldiers who have seen bodies ripped apart also film their own war flicks and edit them, and their buddies add the sound tracks. “Squad videos,” they’re called. Is it a paper that makes these guys appear in a classic heroic mold? Shields is undoubtedly right that photographers and photo editors and retouchers and publishers can all conspire to make a grieving man weeping over his comrade’s dead body appear as a familiar and vaguely sentimental religious archetype. The problem is, the man might really be praying.

Jesse Barron is a writer living in New York.