There aren’t five other living American authors as meticulous and shrewd as Dana Spiotta, as willing (to say nothing of able) to shape true esotericism into such consistently accessible forms. Her novels—four of them to date, arriving roughly every half decade—are taut and scintillant, intermittently comic though without much risk of becoming “comedies,”a quality her work shares with that of her longtime mentor, Don DeLillo. Her new novel, Innocents and Others, reprises many of her signature themes—Los Angeles, film, the long shadow of the ’60s, the loneliness of lives lived in disguise—but the more time you spend with it, the more slippery, original, and uncanny it reveals itself to be.

Meadow Mori—one of the book’s main characters, whose name sounds an awful lot like “memento mori”—is a critically acclaimed maker of what you’ll have to forgive me for calling experimental documentaries, though she hasn’t made a movie in some years. Dogged by rumors of both a mental breakdown and a falling-out with Carrie Wexler, a commercially successful (and slyly feminist) director who has been her best friend since childhood, Meadow has been teaching film at a small college in upstate New York and otherwise lying low.

In an essay for a series called “How I Began,” published by a website called Women and Film, Meadow recalls her senior project at the fancy but freethinking Los Angeles private school where she and Carrie—ostensibly the other protagonist—met and bonded in the early ’80s. For said project, Meadow watched her favorite filmmaker’s most famous film twenty times in a row and kept a running log of her responses: “There is a kind of purgatory that happens on the sixth viewing. You are bored of the repetition, and then you go through it. You are liberated from the narrative, the story. But it is only because you know it so well, and then you can absorb HOW the story is told.” She sent “the filmmaker” a copy of the project, which resulted in a lunch invitation, which led quickly to a kiss, and then to Meadow moving in with him. She spent nine months in his Brentwood home, mere minutes from her own, like some latter-day remake of Hawthorne’s “Wakefield” tinged with a less-rapey Lolita. When the filmmaker died of a heart attack, she packed up her stuff and erased all proof of her having been there, save for a packet of letters the filmmaker wrote to her, which she claims to have kept but never shared.

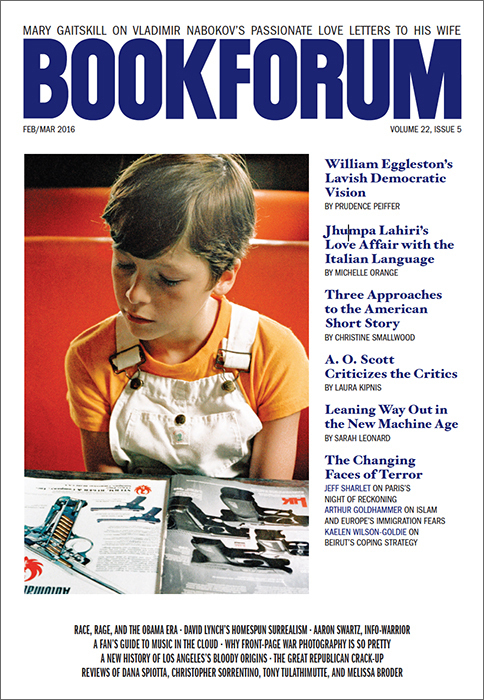

[[img]]

In that same essay, Meadow writes: “A lie of invention, a lie about yourself, should not be called a lie. It needs a different word. It is maybe a fabule, a kind of wish-story, something almost true, a mist of the possible where nothing was yet there.” This does not stop her story from being ripped to shreds in the comments section. Site regulars argue over whether Meadow’s affair—and her confession of it—is a feminist or antifeminist act. Carrie Wexler fans are irritated over the scant notice Meadow seems to take of her. Spambots spam and pseudonymous misogynists troll. Someone figures out that “the filmmaker” must have been Orson Welles (and the film watched twenty times presumably Citizen Kane—as potent a story about origin myths, and memento mori, as you could ask for). It is revealed that Meadow has gotten wrong both Welles’s neighborhood and his date of death. “People, I am calling BS on this whole essay,” writes a commenter who goes by “thelongcut.” It’s as if the concept of the fabule had never been mentioned at all.

Carrie Wexler also writes an essay for Women and Film, but you don’t get to read it until fairly late in the book, and even then it’s largely about Meadow; both women seem to take for granted that Meadow is il miglior fabbro. For a while, Innocents and Others appears to be the story of a friendship between well-matched rivals, and how (or whether) their bond survives the friction and frisson of competing artistic visions, as well as the passage of time. But I eventually came to view the book jacket’s description of the novel as being “about” Meadow and Carrie as a kind of wish-story itself. (Call this a marketing department’s fabule, if you like.) Meadow’s true other—and, in the symbolic system if not the actual plot of the novel, her antagonist—is a woman named Amy, who goes by Jelly in some circles and Nicole in others, and who eventually becomes the subject of one of Meadow’s films.

Jelly (I follow the book’s preference in defaulting to this alias) is twenty years older than Carrie and Meadow, a homely loner who got into “phone phreaking” in the 1980s, during a bout of blindness caused by a meningitis infection. Meadow’s many scenes of watching movies, shooting and editing footage in her studio, and otherwise exploring the mystery and possibility of the visible are juxtaposed with scenes of Jelly alone in the private darkness of her decimated sight and her crappy apartment, talking to strangers on the phone. Jelly is obsessed with the purity of the voice detached from the body. Through a contrivance best not too closely scrutinized, she gains the phone numbers of powerful but peripheral Hollywood men and “seduces” them into conversation. They don’t talk dirty, they just talk—the men sharing personal, even confessional stories, lulled by “Nicole”’s aggressive receptivity. When pressed, she describes herself “accurately but not too specifically: long blond hair, fair skin, large brown eyes. Those true facts would fit into a fantasy of her. She knew because she had the same fantasy of how she looked.”

Like Nik, the rock ’n’ roll Pessoa of Stone Arabia, who has obsessively documented a music-star life that never happened, or Mary Whittaker, the ex-radical wanted for murder and living under a false identity in Eat the Document, Jelly has based her entire life on a fabule, born of contingent urgency but sustained over the long term out of desire as much as need. As the lie and the life grow inextricable, any threat to the first is necessarily seen as a threat to the second. Jelly’s longest phone affair is with Jack, a composer of film scores and the only man who can induce (seduce?) her into giving as well as taking. The relationship they develop in the faintly buzzing purgatory of the twentieth-century landline is genuine and mutually fulfilling, as far as it goes, but Jack wants to meet Jelly, or rather “Nicole,” in real life. Jelly’s attachment to her own fantasy, and, more to the point, her attachment to her fantasy of Jack’s fantasy of Nicole, is stronger than the lure of the real. For Jelly—overweight, aging, robbed of the ability to see or the desire to be seen—the body is a prison. Her ghostly phone life, and her despairing faith in “the failure of the actual to meet the contours of the imaginary,” has become the only truth she can accept.

Meadow, a natural beauty who loves long runs and seems to will suppliant boyfriends out of the ether, remarks of her Welles letters, “Yes, mostly they were about my body, but a body is a part of you, there is no getting around it even if you want to.” Jelly, of course, would concur with this point, but she would also find Meadow’s blasé comfort with it as unimaginable as Meadow would Jelly’s resignation to self-erasure. In the lottery of genetics, as in the rigged game of image culture, one person’s get-out-of-jail-free card is another’s life sentence. For such a person, Joan Didion’s apothegm that “We tell ourselves stories in order to live” is less a cry of battle than of surrender.

Meadow hears the legend of Nicole at a dinner party hosted by her parents, and immediately determines to find this woman and make a film about her. As it happens, Jelly is a film buff herself. Her early memories of falling in love with cinema are as vividly described as Meadow’s own, and they both began film school but dropped out—Meadow because she had the means and confidence to dive right into her practice, Jelly because her illness made continuing impossible. In a different life (one where Jelly was healthier, prettier, born to wealthy and credulous parents), she might have been the Meadow of her generation. Instead she is one of Meadow’s subjects, a reclusive weirdo whose frangible inner life winds up raw material in a stranger’s hands, given over to public view.

“The way to manage a problem,” Meadow thinks at one point, “is not to solve it, which is impossible, but make the problem the material of the film.” This is precisely Spiotta’s method. Innocents and Others is a confrontation with the blessings and curses of the body, the pleasures and costs of fantasy, the impossibility of either total truth or total fiction. It is a work of acute cultural intelligence and moral imagination, and is far too wise to offer anything as paltry as answers to the great and terrible questions that it raises. I am inclined to say, by way of closing, that there is only one thing I am certain of: There are no innocents, only others. But that’s a little cute for a kicker, and anyway the longer I think about it the less I think it’s true. In fact I don’t even know what it means, really, so try this: The conjunction in the title is not meant to describe two discrete statuses or categories of people, but rather to suggest that there is one category, all-inclusive and self-divided; we are always both.

Justin Taylor’s most recent book, Flings (Harper, 2014), is now available in paperback.