What is it about Jane Austen that makes so many writers pay homage to her by rewriting her books? From the film Clueless (based on Emma) to Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary (Pride and Prejudice) to Cathleen Schine’s novel The Three Weissmanns of Westport (Sense and Sensibility) to Curtis Sittenfeld’s new novel, Eligible (P&P again), contemporary adaptations have proven irresistible to a wide range of writers.

I’ve never quite understood the impulse, not least because I can’t fathom why a writer would deliberately court a comparison so unlikely to be flattering to herself. Perhaps the motive is pedagogical, stemming from a desire to demonstrate to modern readers that the novels are still relevant? (Call me a cynic, but I’m skeptical that readers so allergic to older novels that they’ve instinctively avoided Austen will be easily converted.) Or perhaps the whole thing is more of a gimmick, one that offers the marketing department an easy a way to package a novel or film while also lending the project some secondhand cachet. Or maybe, more charitably, it comes simply from an excess of enthusiasm, combined with a reverence so great and humble-making that these writers believe that even the novels’ least-exalted aspect—their plots—are that much better than anything they could come up with on their own.

Whatever the reason for their popularity, the problem such adaptations face remains the same. Of all the components that make up a novel, plot tends to be the least timeless. Unlike character or tone, plot is, and ought to be, grounded in the time and place in which the book is set. If a novel is any good, the inner lives of its characters—and their emotional reactions to one another—will of course reflect but also transcend time and place. So will the author’s ability to comment on, and judge, those characters, both morally and as social actors within their environments. But much of what determines the shape of the plot is external and specific—from courtship rituals to practical matters such as whether characters must wait weeks for letters or are able to communicate instantly with smartphones. Transposing plots to new settings, in which everything from mores to technology have changed dramatically, often leads to situations and outcomes that feel forced.

Take Clueless. Though charming in its (Austen-reminiscent) wit, as a unified work it only half succeeds. The equation of nineteenth-century British class consciousness with contemporary American high school status consciousness is, as a conceit, very clever and makes for great fun. But the romance between Cher, the stand-in for Emma, and her college-age former stepbrother doesn’t translate nearly as well. By contemporary standards it’s a little bit creepy for this college student to be so obsessed with his high-school-age ex-stepsister and so involved in her social life, a problem that didn’t exist in the original because Emma and Mr. Knightley were both grounded in the same grown-up social milieu.

Fielding neatly sidestepped many of these problems by modeling Bridget Jones only very loosely on Pride and Prejudice. Gone were the other four sisters, the creepy cousin, and the mercenary friend who marries him. The key element of P&P that Fielding preserved was the contrast between two unlikely mates—one charming and sexy and selfish, the other stiff and arrogant and kind.

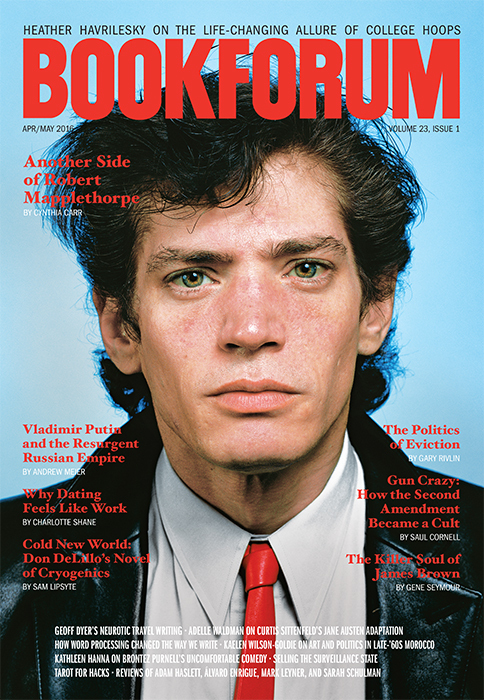

In the latest entrant to the field, Sittenfeld has given herself no such outs. The author of four novels, including the best sellers Prep (2005) and American Wife (2008), Sittenfeld has now produced an Austen adaptation that is highly faithful to the original. This gives it one—extra literary—leg up on a more freewheeling reimagining: Watching how Sittenfeld relocates Austen’s novel to a modern American setting is likely to be one of the book’s primary pleasures for ardent P&P fans. In this, Sittenfeld is often quite ingenious. In her telling, the Bennets are a once wealthy, now slightly shabby WASP family who live in a tony Cincinnati suburb but are unable to maintain their deteriorating Tudor mansion. Mrs. Bennet is a racist with a country-club membership, while Mr. Bennet, philosophical in Austen’s version, is mainly interested in genealogy and family history.

Sittenfeld has made the Bennet daughters significantly older, wisely, given that in Austen’s version the youngest is fifteen—possibly sixteen—when she marries, which might raise a few eyebrows today. In Eligible, the oldest Bennet daughter, Jane, instead of being in her early twenties, is a yoga instructor pushing forty who is in want not so much of a husband as a child, while our heroine, Liz, is a magazine writer in a bad relationship with Jasper Wick (i.e., the rakish Mr. Wickham, aka Hugh Grant in the film version of Bridget Jones).

The younger sisters—Mary, Kitty, and Lydia—live off their parents in the family home, where dour Mary is pursuing her third online master’s degree. Kitty and Lydia—in Austen’s version, empty-headed flirts with a particular interest in soldiers—are empty-headed college graduates who, if less boy-crazy, are no more impressive: They resemble a kind of twentysomething made familiar by reality-TV shows about expensively dressed young women with SoCal twangs and lavish parental support. Sittenfeld tells us that Kitty and Lydia “had never worked longer than a few months at a time, as desultory nannies or salesgirls in the Abercrombie & Fitch or the Banana Republic. Similarly, they had lived under roofs other than their parents’ for only short stretches, experiments in quasi-independence that had always resulted in dramatic fights with formerly close friends, broken leases, and the huffy transport of possessions, via laundry basket and trash bag, back to the Tudor.” Their days are spent eating lunch out, watching videos on their smartphones, and exercising.

Sittenfeld also replicates many of the intra-family dynamics that Austen spelled out—Mr. and Mrs. Bennet are, for example, just as unhappily paired. Sittenfeld does not try to soften the odious Mrs. Bennet or the unappealing Mary. (In Austen, the latter is a homely pedant with “a conceited manner” who “worked hard for knowledge and accomplishments [and] was always impatient for display.” In Sittenfeld’s: “Mary was proof . . . of how easy it was to be unattractive and unpleasant.”)

I was glad to see this, as too many contemporary adapters of Austen lose their nerve when confronted with the more astringent aspects of her worldview, choosing to present a cautiously renovated version. In Ang Lee’s 1995 period-film version of Sense and Sensibility, for example, the youngest Dashwood sister, Margaret, is presented as a lovably impish tomboy with a charming passion for geography and travel. This depiction bears little resemblance to what you’ll find in Austen’s novel. Without any tender qualms about writing off a child, Austen dispenses with Margaret at the end of the first chapter: “Margaret, the other sister, was a good-humored, well-disposed girl; but . . . she did not, at thirteen, bid fair to equal her sisters at a more advanced period of life.” She barely says another word about her for the rest of the novel.

I find it admirable that Sittenfeld adheres to Austen’s un-PC insistence that not all people are equally deserving or interesting. If only she did so a little more artfully! The comparisons that adaptations invite are particularly damaging to Sittenfeld, whose writing tends toward flatness. Her sentences possess little in the way of nuance or playfulness; they convey information, that is all. Many read like lazy attempts to import with declarative statements what Austen laid out with such a deft touch. “Contrary to typical sibling patterns,” Sittenfeld writes, Kitty “both tagged after and was led astray by her younger sister.” That wooden phrase—“contrary to typical sibling patterns”—could have been pulled from a psychology textbook. Mr. Bennet, we are told, has a “sardonic affect,” as if that statement alone will bring him to life. One doesn’t have to recall the original—“Mr. Bennet was so odd a mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humor, reserve, and caprice, that the experience of three and twenty years had been insufficient to make his wife understand his character”—to feel that Sittenfeld’s presentation is weak.

The result is an absence of Austen-style comedy, which derives in large part from Austen’s ability to display her characters’ foibles in crisp scenes. While her Mr. Bennet fires off line after line of zingy dialogue in repartee with his overmatched wife, in Sittenfeld’s world, we must be content largely to take her word about his affect. In place of real human comedy, we are occasionally offered flabby, topical jokes: “A reality show isn’t unlike the Nobel Peace Prize . . . in that they both require nominations.”

Like the famously succinct Austen, Sittenfeld favors short chapters—she simply writes more of them, a lot more. Sittenfeld’s set pieces are digressive, light, and vaguely scene-setting rather than pointed and deliberate—they might describe a trip to a local chili restaurant with geeky Cousin Willie (Mr. Collins from the original) or Jane’s first date with Bingley, from which she doesn’t return home until 5 AM, ample time to “discover that they were a couple truly compatible in all ways.”

As you can infer, Sittenfeld’s characters, unlike Austen’s, sleep with their love interests. Thankfully. I’m not sure this adds much in terms of depth—the sex scenes are fine, no more or less clever or insightful than the rest of the novel—but it was certainly wise to update the plot to this extent, for the sake of plausibility. Other deviations are less felicitous. As Sittenfeld’s book progresses toward its conclusion, it meanders into a long and rather pointless subplot about a reality show (Bingley is the former star of a Bachelor-style program called Eligible). With the predictable logic of a rom-com, the whole Bennet clan eventually winds up on a special episode.

Equally telling, in terms of the book’s sensibility, is the approach Sittenfeld takes with Liz’s character. Austen’s Elizabeth wins the hearts of readers with her wit and elegance of mind; Sittenfeld’s method is more in keeping with a certain set of contemporary fictional conventions. Her Liz is nice and smart but also, crucially, relatable and nonthreatening. That is, she is a serious journalist who interviews important people, including a legendary feminist of Gloria Steinem caliber, but she doesn’t pretend to be better than other people: She likes reality shows. She’s a good person, who helps her parents and sisters, but she’s capable of petty feelings of jealousy. At one point, Liz thinks:

There were many reasons she found her sisters’ enthusiasm for CrossFit and the Paleo Diet irritating, including that Liz herself had been familiar with both long before they had, having written an article about CrossFit back in 2007. Another source of irritation was that her sisters looked fantastic; they had always been attractive, but since taking up CrossFit, they were practically glowing with energy and strength.

A paragraph like this is less a means of crafting the contours of an individual character than it is a quick way of endearing Liz to readers, assuring them that she is human, no better than they are. It calls to mind Meg Wolitzer’s 2013 observation about “slumber party fiction,” populated by characters whom the “reader is meant to feel ‘comfortable’ around . . . as though the characters are stand-ins for your best friends.”

Bridget Jones won us over by being precisely what the original Elizabeth Bennet isn’t: a hot mess, a klutz and a slob, someone who constantly misjudges situations and embarrasses herself but nonetheless presses on with pluck and good humor. The problem with Sittenfeld’s decision to make her Liz so wholly innocuous, without any edge that might make readers feel intimidated, is not that she is unfaithful to Austen. The reason to regret the change is that it results in a much duller book. Austen is a morally demanding writer, judgmental not only of her characters but, implicitly, of her readers, for the ways in which we too fail to measure up to her exacting standards. Her tartness, and her refusal to pander to readers, is key to her appeal.

In Prep, her debut novel, Sittenfeld cast a ruthless eye on the social world of a New England prep school. Her heroine’s observations about her classmates were often as socially acute as they were unsayable in polite company, and so on target that they were apt to make the reader feel exposed. Regardless of Sittenfeld’s intention, it is that novel, and not the imitative but toothless Eligible, that pays a real tribute to the spirit of Austen.

Adelle Waldman is the author of The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. (Henry Holt, 2013).