In 2008, Matthew Desmond moved into a trailer park on the southern edge of Milwaukee, where most everyone was white. A few months later, he relocated to a rooming house on Milwaukee’s heavily African American north side. There, he lived with a security guard who worked at the trailer park. Desmond was a budding sociologist pursuing his graduate degree at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, an hour west of Milwaukee. His aim was to better understand life at the hardscrabble margins of the housing-rental market.

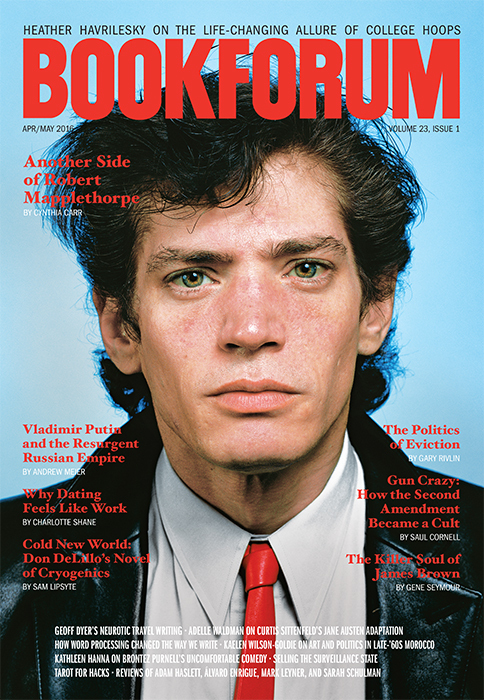

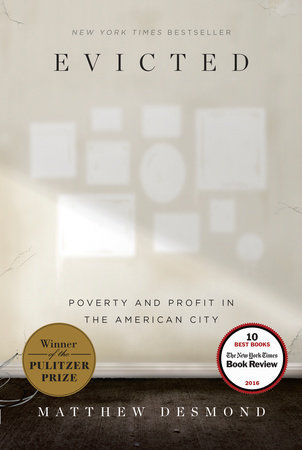

Desmond is white. His neighbors at the trailer park thought he was crazy to move to the black part of town. People he encountered on the north side also seemed to think he had lost his marbles—or that he was either an undercover cop or a spy for the landlord. Presumably, some had likewise doubted his mental health when he moved into a trailer park so wretched that, at the time, city hall was seeking to shut it down. Maybe all these onlookers were right to question Desmond’s sanity. But the result of his odyssey among members of the down-and-out renter class is a terrific new book, Evicted, an intimate and beautiful work as poignant as it is insightful.

Schlitz and Pabst had long since boarded up their breweries by the time Desmond arrived in Milwaukee. A large portion of the city’s manufacturers had relocated to the Sunbelt or found a new home overseas. Half the city’s working-age black men didn’t have a job, and the half who did were mostly working in the service economy and making less money than they would have during Milwaukee’s postwar manufacturing heyday. Real wages among the working and middle classes remained flat, in Milwaukee and the rest of the country, as housing costs continued to soar. That’s the contradiction that informs Desmond’s book and keeps us turning the pages. A run-down two-bedroom in what he describes as “one of the worst neighborhoods in America’s fourth poorest city” was going for around $550, utilities not included. Yet a minimum-wage worker brought home barely $1,000 a month, and a mom with two kids on welfare less than $650. The poor and working poor are generally living beyond their means—but they’re already living at the bottom of the market. They perform the impossible simply by paying their bills each month, until they can’t.

Desmond tells his tale through an ensemble cast of characters he met during his months in Milwaukee. A man he calls Scott (the deal with his subjects, alas, had him trading access for anonymity) had been working as a nurse until wrenching his back. By the time we meet Scott, he’s living in the trailer park, and an addiction to pain pills has ripened into a heroin habit. He’ll later be evicted after falling behind on the rent, as will Larraine, who was scraping by on a $714-a-month disability check (she had fallen out of an attic window) but paid $550 a month in rent. A couple Desmond calls Pam and Ned, both crack users, were also living at the trailer park. Pam was eight months pregnant when they were evicted, and Ned was wanted by the police.

The book’s stars, however, are the women Desmond met after he moved to the north side. There’s Vanetta, a mother of three, who faces a dilemma after the Old Country Buffet cuts her hours. If she pays the utility company the $705 she owes, she won’t be able to afford the rent. But if she pays the rent, she fears that Child Protective Services will seize her kids because they live in a home without lights or gas. Early in Evicted, we meet Arleen, a single mother paying $550 in rent while trying to raise two boys on $628 a month; simple math tells us that things will end badly for them. Then there’s eighteen-year-old Crystal—a volatile, fragile young woman who as a foster child bounced among dozens of homes. Crystal’s crime, in the eyes of her landlord, was that she repeatedly phoned the police to report that a neighbor was being beaten by her boyfriend. She, too, would be evicted.

Race plays a huge role in Desmond’s tale. Crystal and Vanetta each wanted to live in a safer neighborhood. Both sought “to leave the ghetto,” Desmond tells us, but landlords anywhere beyond the north side turned them away. The black/white divide becomes most palpable when Desmond shows up to witness the eviction of one of his characters. Roughly one in four residents of Milwaukee County is black, yet three-quarters of its evictees are African American; of those, three-quarters are women. Desmond couples that statistic with the astonishingly high rates of incarceration among black men from impoverished neighborhoods. “Poor black men were locked up,” he writes. “Poor black women were locked out.”

The shelters where many low-income people land after they’re booted from their homes always seem full when one of Desmond’s displaced neighbors needs a bed. Several go homeless, while others hole up with family or friends in places that are hardly a refuge. Arleen called ninety landlords before finding a decent one-bedroom for $525. But her teenage son, who had attended five schools in two years, kicked a teacher in the shin during an argument. The police were called, the landlord freaked, and less than a month after they moved in, Arleen and her two sons had to move out. Arleen’s next stop was the apartment of a friend who, she would soon learn, was turning tricks in Arleen’s bedroom. Vanetta would apply for seventy-three apartments before settling on a dump with a clogged kitchen sink, grimy floors, a front door that didn’t lock, and a drug crew on the corner. “It’s wretched, but I’m tired of looking,” Vanetta tells Desmond. Eviction is not simply an outgrowth of poverty, he tells us, but also, at times, the cause of it.

Ostensibly, we have policies in place to help those living on the economic margins, including rent-reducing housing vouchers, which try to ensure that low-income families pay no more than 30 percent of their income in rent. But the voucher waiting lists are so long that in Milwaukee, as in many other cities, the authorities don’t even bother adding new names. So those scraping by end up in a place like College Mobile Home Park, whose owner, Desmond tells us, was making more than $400,000 a year renting out 131 dilapidated trailers. Or they meet a person like Sherrena Tarver, the landlord who will evict Arleen, Crystal, and other characters in the book.

Tarver, who is black, plays a central part in Evicted and lends considerable nuance and depth to Desmond’s tale. At first you feel for Tarver, an up-by-her-bootstraps former public-school teacher whom the author dubs an “inner-city entrepreneur.” (Tarver also runs Inmate Connections, which sells lifts to people wanting to visit a loved one in prison.) “Love don’t pay the bills,” she rightly says. But as the travails of Desmond’s subjects unfold, Tarver reveals herself to be just another slumlord, ignoring calls to clear a clogged sink or fix a broken window. She doesn’t install smoke detectors in sleeping areas, as the law requires her to do, which becomes an issue when one of her buildings burns down. “If you ever thinking about becoming a landlord, don’t,” Tarver tells Arleen after giving her a ride home from court, where a judge has sided with Tarver and ordered Arleen and the kids out of the apartment. “Get the short end of the stick every time.” That was just before Tarver and her husband, who together cleared more than $100,000 a year as landlords, took their annual trip to Jamaica. They had recently purchased a three-bedroom condo in Florida.

Often you hear that an author writes well for an academic, as if he were being graded on a curve. But Desmond is a good writer, period. His prose is vivid and energetic; his physical descriptions can be small gems. Helping his cause is the digital recorder he kept running in his pocket. He felt social scientists were ignoring evictions as a research subject, so in 2009, he initiated the Milwaukee Area Renters Study (MARS), a three-year look at his adopted town that has been hailed as a landmark undertaking. After completing his graduate degree, he went on to join the faculty at Harvard and, at the age of thirty-five, win a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2015. You might hate him, if not for the size of his heart and the compassion he unerringly shows his subjects.

Wisely, the professor lays off the dense language of sociology and policy prescriptions until the epilogue. By then—with Arleen and Vanetta and the others firmly in our minds—we are horrified to learn that every year, “families are evicted from their homes not by the tens of thousands or even the hundreds of thousands but by the millions.” The book concludes with a demand that we treat affordable housing as the full-blown crisis it has plainly become. Three-quarters of the low-income families in the United States who qualify for housing assistance don’t receive it, which is why more than half of Milwaukee’s poor renters spend at least half their income on rent, and one-third pay more than 80 percent.

“Imagine if we didn’t provide unemployment insurance or Social Security to most families who needed these benefits,” Desmond notes. “Imagine if the vast majority of families who applied for food stamps were turned away hungry.” Alas, none of those scenarios seems hard to imagine, and certainly all seem depressingly more likely than Desmond’s call for a universal voucher program and a corps of publicly funded attorneys to represent low-income families in housing court. A young, talented sociologist can open our eyes by taking us somewhere we’ve never been. The hard part will be getting policy makers to care.

Gary Rivlin is the author of five books, including, most recently, Katrina: After the Flood (Simon & Schuster, 2015).