DO PEOPLE STILL REMEMBER Betty Broderick? She was the San Diego career stay-at-home mother—I see no oxymoron there—who killed her ex-husband, Dan, and his new wife in 1989. She tried to position herself as an Everywoman who’d been discarded for a younger, thinner model. But the stubborn fact remains that she drove to her ex’s home with a gun, then shot him and his wife while they slept. This came after a contentious separation and divorce that took several years, with plenty of bad behavior on both sides. The real-life details of the case are much worse than what was dramatized, quite memorably, in two television movies.

When Los Angeles Times reporter Bella Stumbo chronicled the ugly Broderick case in Until the Twelfth of Never (1993), some reviewers contended that the book was too sympathetic to Betty at Dan’s expense. But Stumbo’s approach strikes me as remarkably evenhanded—which is to say that both Brodericks come across as uniformly awful. Their mutual abuse was emblematic of nothing except their own stunted souls, and an insatiable yearning always to win. What they hoped to win was never very clear. Betty Broderick remains in prison in California. At her 2010 parole hearing, her first, she continued to insist that she wasn’t really responsible for her actions. The state disagreed—and despite what critics may have initially feared, readers of this harrowing study are likely to second that verdict. —Laura Lippman

THEODORE STURGEON’S Some of Your Blood (1961) is little known and in no ordinary manner a crime novel—but then, it’s unlike any other book I’ve read. It does contain a crime, or a supposed crime, and the idea of working toward the solution of a mystery lies at its heart. But it’s above all about individuality and independence, about a relationship between a man and a woman and the many ways this can be challenged and confounded by society. The novel’s telling is every bit as brilliant and offbeat as its subject matter: Beginning in the second person and incorporating letters, transcripts, and therapist’s notes, it shifts and shape-changes as you make your way through it. Sturgeon did also tackle the theme of American criminality more directly: I refer the reader to his prescient story “And Now the News . . . ,” a writerly thinking-to-oneself about the roots of crime. —James Sallis

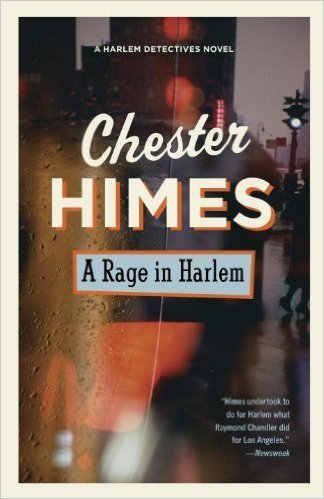

IN NOVEMBER 1956, Chester Himes was in Paris visiting the offices of his publisher, Gallimard, and ran into Marcel Duhamel, who had translated If He Hollers, Let Him Go into French. Published in the US in 1945, Himes’s first novel was pigeonholed as “protest” literature—an earnest plea for Negro rights—rather than understood as the devastatingly smart satire it was. Himes had continued to toil, prolifically if obscurely, through several more novels written in his exquisitely sardonic voice.

Duhamel heard something he liked in that voice. He was not only a translator. He was also the director of the Série Noire imprint, which specialized in crime novels, or policiers, as the French called them. Duhamel told Himes he should try his hand at the genre. Himes was intrigued by the literary challenge. And, as he told French radio years later, “I needed the money desperately.”

After a couple of weeks, Himes showed Duhamel his first eighty pages: a wild story about a southern hick in Harlem, lost in a phantasmagoria of hoodlums and hustlers. Duhamel loved it. Himes asked if he thought he should add some cops to the story. Duhamel said, “You can’t have a policier without police.”

The problem was that Himes—who had spent nearly eight years in an Ohio state penitentiary for armed robbery—hated cops. He knew that if he were going to write about black cops, they would have to be the baddest mofos in Harlem. So he created Detectives Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. They suddenly appear in chapter 8 of A Rage in Harlem, published in 1957, and would become the main characters in the subsequent eight volumes of Himes’s Harlem crime epic. “Colored folks didn’t respect colored cops,” Himes writes. “But they respected big shiny pistols and sudden death. It was said in Harlem that Coffin Ed’s pistol would kill a rock and that Grave Digger’s would bury it.”

Thanks to the suggestion of a French editor, Chester Himes had taken the American crime novel to the black part of town. —Jake Lamar

THE SUCCESS OF a true-crime book rests largely on its narrative structure, and the best writers in the genre are master builders—shaping events that are often chaotic and unfair into stories with depth, meaning, and suspense. They find sense in the cruelest twists of fate, pacing in the often plodding path to justice, surprises lurking within stories we all thought we knew.

Some material, however, seems too unwieldy for the confines of a book—and on paper, the case depicted in Footsteps in the Snow (2014) seems a perfect example. The 1957 murder of seven-year-old Maria Ridulph in DeKalb County, Illinois, went unsolved until 2012, when, after fifty-five years, two hundred suspects, and a seemingly endless series of bureaucratic blunders, false leads, and police regime changes, Jack Daniel McCullough, then seventy-two, was found guilty of the crime. Add in two shattered families, a series of shocking, long-buried secrets, and even a deathbed confession, and you’d think it impossible to tell this story in five books, let alone one. However, author Charles Lachman brings the five-decade saga vividly to life in a stunning achievement of structure and characterization. Across five hundred pages, Footsteps in the Snow is by turns compelling, terrifying, frustrating, and tragic, but never confusing, never dull—and never, even for a moment, unwieldy.

Incredibly, the case took yet another jarring turn at the end of March, when DeKalb County prosecutor Richard Schmack announced that, after going over the evidence, he had determined that McCullough was wrongly convicted. His predecessor, Clay Campbell, has called the new decision a “travesty.” As a reader, I can only hope that the crime will be solved once and for all—and that Lachman will write a sequel. —Alison Gaylin