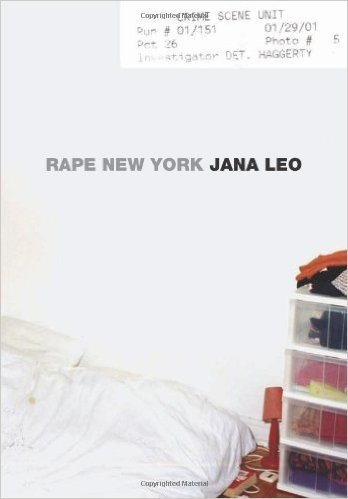

THERE’S A STORY about New York gentrification that everybody knows, in which the city gradually Disneyfies into a playground for tourists and well-heeled locals, prices rise, and crime falls. But is it true that New York has grown safer, or just an American fantasy? Spanish artist and academic Jana Leo has another question: Safer for whom? In her 2009 book, Rape New York, which describes the assault she suffered at gunpoint in her Harlem apartment and its aftermath, she offers a disturbing account of gentrification as a process far dirtier, more violent, and more criminal than it may appear.

In Leo’s view, there’s nothing bland, impersonal, or accidental about the forces changing New York’s landscape. Violent crime plays an integral role. She notes that at the time she was raped, her landlord had left the building unsecured—locks stayed broken, people moved freely through the halls and across the roofs. When residents were attacked in their apartments, the landlord’s office responded, “Do you think you live on Park Avenue?” Leo lays out a (conspiracy) theory of Harlem real estate as a system in which minimum security makes for maximum profit:

Containing crime in specific buildings reduces their value. . . . Not only were developers able to buy property on the cheap, the scam also made short-term, low-income rentals much more profitable than high-income rentals. . . . Crime was facilitated by a lack of security in the common areas, encouraging a rapid turnover of tenants. Agents kept the security deposit, increased the rent, and charged illegal brokers’ fees, thus quickly realizing a profit from the quick turnover. . . . Eventually the building would fall completely vacant, and was no longer subject to rent stabilization laws. It would then be demolished or converted into luxury housing.

Leo’s slim book is a unique anatomy of violence that’s both systemic and intimate. It’s also a blunt undoing of another American fantasy, that of being safe in your own home. She reminds us that rape is not a rare event, and that it usually doesn’t take place in dark alleys. For women, “the home is a high-risk situation.” Rape, Leo notes, is so routine an occurrence in New York apartment buildings that the law has a specific provision (“Article 16”) for dividing the blame for it between attacker and landlord. If your rapist has been convicted and you sue your landlord for inadequate security, jurors must decide their relative responsibility on a percentage basis. You could call this a kind of grotesque tax on the landlord’s lucrative business—a low one, and one he can hope to reduce still further by bribing the assailant (usually poor and himself trapped in a hostile system) to take more blame and absolve the landlord of his liability. Leo’s rapist tells her lawyer that the landlord’s people have been in touch and “might offer me something” to say what they want him to: We can’t know what “something” is, but we suspect they got him cheap—a rare steal in New York real estate.

Lidija Haas is Bookforum’s associate editor.