THE DEEP APPEAL of nonfiction is the massive and thorny dialectical tension between “true” and “truth.” How much overlap is there? Which one gets privileged? Which one drives the operation? It is a dynamic that feeds all the nonfiction genres—memoir, journalism, narrative history, biography, criticism, self-help, and true crime. In true crime, specifically, all along the spectrum from the most tawdry (Helter Skelter) to the most elegant (The Journalist and the Murderer), facts are in a pitched battle with storytelling. Crime leaves behind facts aplenty: scenes, corpses, forensics. Yet most of us aren’t really in it for the facts; we want the equation, the story. In the world of psychotics, soullessness, and heinous criminality, we want to know how bad it can get, if it’s solvable, preventable, local, and, perhaps most importantly, contagious.

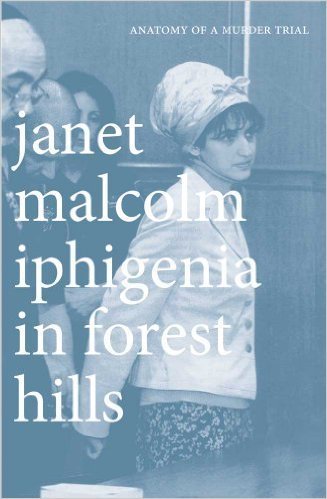

In the opening pages of Iphigenia in Forest Hills (2011), a procedural about the murder trial of Mazoltuv Borukhova, a doctor charged with hiring the assassin who killed her estranged husband, Janet Malcolm writes, “If any profession (apart from the novelist’s) is in the business of making things up, it is the profession of the trial lawyer.” She thus assures the reader, right off the bat, that the facts to be presented in the courtroom—fingerprints, cell-phone logs, bank records—will not add up. The justice system will operate under the auspices of competing fabrications and decidedly will not provide the truth equation for the crime.

Malcolm is a consummate strategist. She comes at her stories obliquely, destroys

preconceptions (say, that a murder trial will provide a fascinating portrait of a murder—like on TV), and then with an almost clinical dispatch redirects attention. What’s interesting about the Borukhova trial is not whether the accused contracted the assassination of her husband—which took place on a playground in front of their daughter—amid the upheaval of a messy custody battle. Rather, it is the story of what, if she were guilty, could drive a mother to such extremes. And of how motivation, whether that of the defendant, the judge, or the unstable lawyer, can become in the court of storytelling so much more consequential than evidence.

One of Iphigenia’s many questions: Can a capricious family court provoke murder, or was Borukhova born a psychopath, fated to her actions? Throughout her investigative work, from one villainous bramble to the next, Malcolm is brilliant and irresistibly vexing. For her, observable truth lies not in the collection and skillful organization of facts but in the reliable complexity and inexplicableness of human behavior. Which is contagious.

Minna Zallman Proctor’s book of essays Landslide will be published in 2017 by Catapult.