There is a moment of reckoning in every married woman’s life when she looks around and says to herself, “This support position was falsely advertised as an exciting leadership opportunity.” Someone in HR sold her a bill of goods. Happily ever after, she now realizes, is a trick they play on you, to turn your life into a blur of breast pumps and dirty laundry.

No wonder the 2002 marital-angst anthology The Bitch in the House was a best seller. Edited by journalist and novelist Cathi Hanauer and featuring seasoned writers such as Vivian Gornick and Daphne Merkin, the collection zeroed in on the precise moment when, having been told she’d be adored by her new prince forever and ever, Cinderella is led back down to the cellar where the mops and brooms are kept. Recognizing just how deeply ingrained patriarchal notions of marriage still are (no matter how liberated all parties involved claim to be), the book’s contributors refused to tiptoe around their anger and disappointment. Instead, many of their stories seemed to suggest that as long as mainstream culture turns married women into handservants, those handservants will become what mainstream culture calls bitches.

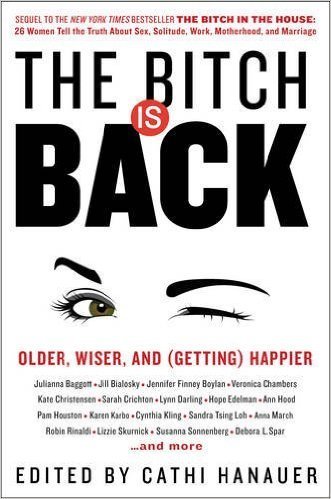

But as gratifyingly familiar as that old sea shanty about the bewildering injustices of our shared heteronormative fantasy can be, there comes a time when a brave sailor must either mutiny, jump ship, or learn to be a happier deckhand in spite of it all. Cue Hanauer’s engrossing sequel, The Bitch Is Back: Older, Wiser, and (Getting) Happier (William Morrow, $27), in which fearless contributors from Ann Hood to Lizzie Skurnick encounter a wider range of challenges, from the dark clouds of middle age to the violent storms of single parenting to the flat sea of a sexless marriage. The writers have far less in common this time around, their personal stories are more varied, and most have long since abandoned the relatively tedious question of whose turn it is to swab the deck.

Which is not to say that the handful of the essays in The Bitch Is Back that are follow-ups to entries in The Bitch in the House don’t offer the suspenseful delights of any story that remains “To Be Continued” for fourteen years. Did Pam Houston, an adventurous and independent dog and horse lover, finally adopt a kid? (No, but she’s had the realization that “I really like (crave, need, require) being alone.”) Did Kerry Herlihy, the unapologetic mistress who described having a married man’s baby in the first book, ever regret any of her decisions? (No. Her commitment to living without regrets remains unbroken, heartbroken first wives and children notwithstanding.) Sadly, some of the best essayists from the previous book didn’t contribute to the new version (Elissa Schappell’s excellent essay on parenting and anger has no second act, for example). But there are many welcome additions to the roster as well, like Sandra Tsing Loh, who offers an entertaining essay about life in the wake of her well-documented divorce.

As lively as this before-and-after experiment manages to be, the weaker essays in The Bitch Is Back read like extra-long dispatches from a relative overseas you haven’t heard from in a while. After so much flat, chronological recounting of life events, it’s hard not to long for something slightly more sublime: a through line, a theme, a moment of grace, a moment of regret. Complicated subjects like marriage and sex are sometimes reduced to leaden observations: “Having regular sex with him seems to bridge some sort of divide,” Grace O’Malley informs us in “Once a Week,” serving up the kind of passionate prose you might find in a DVD player’s instruction manual.

In particular, the last few paragraphs of many of the essays in The Bitch Is Back are disappointingly generic and mundane, like the tail end of a complex conversation that unexpectedly becomes reductive as it draws to a close. Debora L. Spar’s otherwise hilarious and honest essay about our medically aided fixation on the fountain of youth ends with a predictable resolution “not to pass judgment” (“If a middle-aged movie star feels she needs to rearrange her face to maintain her career—or even just to feel prettier—who am I to criticize?”). Many of the essays end with a strong-armed look forward that begins to sound almost rote: “I can’t know what comes next, but I do know this”; “The divorce jury is still out for the moment”; “Sometimes I think about the future”; “I will learn what happens next”; “It’s an ongoing experiment, but so far . . .”

Generally speaking, personal essays are not improved by an impulse to address every single emotional angle, and then wrap up by foreshadowing the future in an awkward effort to bring closure. The results tend to sound less like artfully crafted essays by smart women and more like a physician’s lackluster notes. The push to tell a story with a clear moral often encourages writers to cast every decision as the best one possible, forcibly transforming the sacred rhythms of everyday life into an unbroken victory march, punctuated by extended bursts of own-horn tooting.

The best essays in The Bitch Is Back resist the need to explain everything, opting instead for incomplete yet provocative snapshots of life’s uncertain transitions. Instead of keeping meticulous score of the writer’s wins and losses, we veer into poetic territory without undue hand-wringing or fanfare. In “Second Time Around,” for example, Kate Christensen describes falling in love with a much younger man after her marriage fell apart, laying out the common traps of self-hatred and self-blame before shifting into an unabashedly earnest and heartfelt tone that embodies what happens when a woman’s anger yields to compassion—for herself and others. Christensen’s language is simple, but her words are buoyed by a palpable sense of acceptance and of being at peace with herself that doesn’t require an effortful attempt to tie all of the facts of her story into a very pretty, very tight bow.

In an impressionistic, pensive essay, Jennifer Finney Boylan charts the perils of coming out as a trans-woman to her wife and sons with a mix of fear and wonder, underscoring both the gratitude she feels for her wife’s loyalty and the growing importance of deciding for herself who she wants to be and how she wants to live. In the midst of this maze of big questions, we share a moment with the author in an Amtrak observation car, when a woman next to her begins singing “Here Comes the Sun” and the other passengers join in. Times like these, the author suggests, make it possible to appreciate “the strange blessings of turbulence.”

The Bitch Is Back returns repeatedly to this effort to view disappointment and loss as inherently instructive or valuable. “My War with Sex,” Lynn Darling’s observations on life (and lust, and longing) after breast cancer, evinces a strangely stoic flavor of optimism: “There were days when I lay in bed staring out the window at a single birch tree, as if fixing on its sunlit beauty was like clinging to the only spar in a vast and very dark sea. But the birch tree reminded me of how large the world was and how unimportant was my place in it. It became a reminder: to let things be what they were, to live unsentimentally. To pare away the unnecessary neuroses, the compulsion to be at the center of every thought; to look at the world without the intervening lens of self.”

When the bitch comes back, in other words, she’s sometimes armed with the wisdom that comes from knowing what is essential, and therefore worth fighting for, and what can be let go. Maybe she recognizes that she’s been undermining her own exciting leadership opportunities as if they were merely support positions for years now. And maybe it’s finally time to leave the mops in the cellar and glide upstairs, gown or no gown, knowing that she belongs in the sparkling moonlight.

Heather Havrilesky is a columnist for New York magazine and the author of How to Be a Person in the World (Doubleday, 2016).