You are heading into the future on a voyage of sexual discovery, and here is what it’s like. Drinking beers with a man you’ve just met online, you think of five or ten other men you already know and would prefer to drink with, were it not for the grim necessity of finding a boyfriend. At Burning Man, you accompany a relatively attractive guy into the so-called orgy dome, but find only other heterosexuals having sex in neat pairs. At a shoot for a website called Public Disgrace, you join an enthusiastic crowd to watch a cheerful twenty-three-year-old being bound, gagged, and penetrated with a beer bottle; the bystanders are encouraged to shout “worthless cunt!” at her, but one man can’t help adding: “You are beautiful and I’d take you to meet my mother!” You consider sex-camming with a random stranger, but decide it’s not worth the risk that a critical mass of the magazine editors you write for—married, middle-aged, male—could lose respect for you. (What would Joan Didion do? It’s safe to say she wouldn’t cam: “She went to San Francisco in 1968 and didn’t even do acid.”) In a nondescript, carpeted room at the headquarters of a group dedicated to the practice of “orgasmic meditation,” a male acquaintance brings you to orgasm with his hand while you stare blankly at a coffee urn on a table.

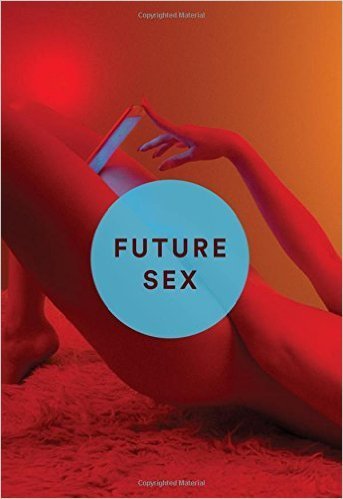

This is sex in America, as filtered through the sensibility of Emily Witt, who has now transmuted several of her sharp, wry personal essays into a book enticingly called Future Sex. Witt is a participant-observer, usually revealing rather more of herself than you’d expect from a reporter, rather less than you’d want from a memoirist. What is most distinctive in her writing is its tone, a sweetly ironic, melancholy deadpan that makes you feel she’s looking straight at the things she describes, not quite wide-eyed and not quite world-weary. She’s like a twenty-first-century gonzo journalist, only instead of using her zany adventures to show how insane her environs really are, she displays a mixture of hope and detachment that exposes almost everything as slightly disappointing, that supposedly fun thing you’ll never do again. When a good time creeps up on Witt, it tends to feel like an accident. Sex, which has defeated many a novelist, being so vastly different to experience than it is to observe, may be the ideal subject for this treatment—zoom out just far enough from the action, and it’s easy to think: Why would anyone want to do that?

One of Witt’s great strengths as a reporter is the steadiness of her gaze: She looks long enough to notice both what is valuable in the seemingly comical or bizarre and what’s ludicrous in the ostensibly normal. As she explains, mainstream dating sites evolved into what marketing execs call a “clean, well-lighted place” because women didn’t want to use services that addressed sex too overtly, and Witt herself is among the many who automatically disqualify any man who makes an explicitly sexual approach online. It makes sense, and yet, Witt points out, it also makes looking for a date on the Internet absurd, “like standing in a room full of people recommending restaurants to one another without describing the food. No, it was worse than that. It was a room full of hungry people who instead discussed the weather. If a person offered me a watermelon, I would reject him for not having an umbrella.” Equally incongruous, when you come to think of it, is the hope Witt discovers within herself “that if I enjoyed going to a museum with a man the sexual attraction would just follow, without anybody having to talk about it.”

On the other hand, Witt finds glimpses of what she’s missing in unexpected places. Porn, far from being the airbrushed self-loathing factory it’s sometimes presented as, can offer diversity and adventure, “a wilderness beyond the gleaming edge of the corporate Internet and the matchstick bodies and glossy manes of network television,” boasting tattoos, fluids, body hair, “Mexican wrestling masks, birthday cake, ski goggles.” Viewers can find all kinds of gloriously messy imperfection, and many porn practitioners evince an autonomy, confidence, and solidarity that often elude Witt and her civilian friends. Chaturbate, a live webcam site whose homepage presents an “overwhelmingly gynecological perspective,” along with a flood of men declaring their eagerness to ejaculate on any available body part, turns out to offer a far weirder, freer set of possibilities. Witt seems bemused and irritated by the somewhat cultish orgasmic meditation community, which consciously-uncouples the female orgasm from the context of romantic relationships or even what you’d normally call sex. Yet she appreciates their efforts to find a form of sexual pleasure for women based on “immanent desire instead of an anxiety to please,” and has some sympathy with their apparent view of heterosexuality as inherently tragic: “Women have been trained,” one OM-er observes, “to think that men don’t want them to be happy.”

At times, Witt’s tone makes it hard to know how to interpret the material she presents. Toward the end of her chapter on online dating, she includes the story of a female friend who spent several years regularly initiating sex with strange men via the Casual Encounters section of Craigslist. The woman describes it to Witt as a period of mostly happy exploration. The men were often sexually skilled, open-minded, delighted to be with her. She felt good about her body, satisfied, in control. Directly seeking something she wanted, she found that it was available—in abundance. Witt contrasts this experience with her own more timid forays into online dating. But it’s not quite clear what she thinks of her friend’s story. Is it an indictment of conventional dating? (If you’re seeking respect, affirmation, or tenderness, look literally anywhere but here.) Does it imply that the only way for a straight woman to avoid disappointment with men is to lower her expectations further than she’d thought they could go? Or are we meant to find it moving, as I did, a sign that connection and warmth may be found easily, even in contexts where you might expect something at best transactional or at worst dangerous?

When parts of this book originally appeared, in the London Review of Books and n+1, the effect was different. An essay can slink in, full of gentle ironies and sly revelations, and then retreat, leaving you to draw your own conclusions. The book, though, has a protagonist; it has an arc. In a sense, it’s a quest narrative: Witt is someone with a problem to solve. She’s a thirtyish, straight, single woman with a lot of sexual freedom but not much idea how to enjoy it. She has slept with many of the men she knows, and assumed that in doing so she was simply passing the time until the future would mysteriously arrive: a transforming, defining love, “the default denouement of my sexuality.” Now it occurs to her to start looking around for some alternative—hence her adventures among the Chaturbaters, the orgasmic meditators, the BDSM performers, the Burning Man polyamorists.

In Witt’s book, sexual problems often turn out to be narrative ones. Sexual freedom—a little sad, a little empty, a lot of pressure—announces itself in a form not unlike writer’s block, “a blinking cursor in empty space.” Despite her title, Witt’s real subject is not the future of sex. Her concern is an existential one: How should we live, and what stories can we tell ourselves about the lives we choose? Her own automatic faith in the traditional narrative, in which a permanent partnership will eventually appear and impose order on the confusion, strikes her as a bit silly. The idea of the monogamous happy ending is out of sync with her time and her impulses, but she doesn’t yet know what to replace it with: “My sense of its rightness, after the failed experiments of earlier generations, was like the reconstruction of a baroque national monument that has been destroyed by a bomb. I noticed that it was familiar but not that it was ersatz.” As she gradually abandons her marriage plot, she considers replacing it with a form of picaresque: Instead of leading in a straight line toward the love of her life, sex could be a different kind of narrative force, propelling her from one intriguing character or circumstance to the next.

Yet as she trawls the Internet, San Francisco, and other stereotypically futuristic arenas for new possibilities, she uncovers a more fundamental problem, a personal version of Freud’s old question: What does an Emily Witt want? Here, her formidable gaze falters. The reporter seeking out our sexual frontier finds she has difficulty identifying her own desires, and may not even wish to know what they are. Of her initial skittishness about porn she says, “I did not want to be turned on by sex that was not the kind of sex I wanted to have.” And when called on (during an especially embarrassing endurance test with the orgasmic-meditation crew) to respond to the question “What do you desire?” she becomes “conscious for the first time of the flat white screen that rolled down when I considered such a question, the opaque shadows of movement behind it. A vacant search bar waited, cursor blinking, for ideas that I, who did not consider an idea an idea until it was expressed in language, had never expressed in language.” Forcing herself to answer nonetheless, she locates only another double blank: “What I said I desired was to surrender to another person without having to explain what I wanted.”

In its quiet way, this is a tough moment for Witt, and for her reader. Must we women be such strange and pitiable creatures, I thought, doggedly looking for love on Tinder and for sex at the museum, preferring to never get what we want in bed rather than have to know, let alone come out and say, what that is? I was impressed that Witt had included this in the book, when other things (like part of the to-cam-or-not-to-cam dilemma, which originally appeared on Matter) seem to have been left out. A woman writing about sex and love in the first person is vulnerable to criticism, even contempt. You can easily imagine a hostile crowd response. After all, Witt is free of most of the historical burdens that could apply and seems to have enough time, money, and options. The taboos that operate in her circles don’t come with many really punitive consequences. Even as a sympathetic reader, I caught myself thinking: Just what would it take for her to enjoy herself?

The great time that isn’t quite being had is one of the book’s central mysteries. Witt catalogues the outlandish activities she could pursue and observes how few she actually considers. Of the media panic over Tinder and the like, she notes that “even the opprobrium was idealistic.” Whatever free-for-all new websites and apps might in theory facilitate, most people’s experience will continue to be defined by loneliness and inhibition. In the 1960s, all kinds of freedoms had been tried out; growing up in the wake of these escapades, Witt’s generation “had questioned very little about their expectations for adult life,” assuming that most alternatives to the nuclear family had proved too messy, risky, complicated, or hurtful to be worthwhile. Better to break the odd onerous rule than to abandon rules altogether, or try to make new ones. The happy ending Witt envisions at the start of Future Sex is one everybody already knows is illusory, if not a form of kitsch. Even the marriages that don’t fail are unlikely to answer the questions that trouble Witt, and a fair proportion of the Chaturbate ejaculators, OkCupid bores, and OM cultists she encounters are probably married already. Still, shoring up the old fantasy is frequently seen as the least bad option: “Even my most sexually adventurous friends remained willing to risk the hypocrisy, dishonesty, diminished sexual desire, or mute unhappiness of many marriages.”

It’s clear from Witt’s account that what makes the prospect of a stable, monogamous partnership so hard to ditch is not that it’s a good cure for uncertainty, dissatisfaction, or existential angst. Many of us are more concerned about where our sex lives will “land us in the social order”: Established couplehood is a mark of status. As the journalist-provocateur Julie Burchill once put it, anyone reaching their mid-thirties without having been married at least once risks giving the impression that they’ve “been sexually tried and rejected by a whole generation.” More to the point are the material signs of order, comfort, and success that Witt tries to interpret in the homes of married or cohabiting friends: “I looked for guidance in their towels and coverlets, the organization of the shared closet, their cake stands or seltzer machines.” Even the bright young things she interviews in San Francisco, millennials who don’t share her tired wariness of nonmonogamy, are worried about how their unconventional dating practices might affect their reputations at work. There’s still a price to be paid for any true commitment to a different mode of sexual and social organization—and even the minority who can afford to dabble semiregularly would hesitate to pay it.

What’s the real reason, then, here in the high-tech future, that our sexual and romantic imaginations still seem so limited? Witt’s relative lack of obstacles makes her a striking test case. Even with every advantage, how free is she? How many viable alternatives does she really have? Late in the book, Witt offers a brief, calm reminder of various unsexy, intractable, old-fashioned problems: the absence, for decades now, of any major advance in contraception; the exorbitant cost of basic health care; and the fact that the US still doesn’t guarantee paid leave for parents. For Witt, the Ur-disappointment is that her country still has “a lot of respect for the future of objects, and less interest in the future of human arrangements.” (Gadgets aside, who could tell the difference between the Jetsons and the Flintstones? Both are from the 1960s, of course, but that’s precisely the moment Witt identifies as the last time Americans had a serious go at imagining what a different future might be.) “The history of the sexual vanguard in America,” Witt writes, comprises “a long list of people who had been ridiculed, imprisoned, or subjected to violence.” But as she also implies, while the US has sometimes been pretty good at punishing free love or other threats to the status quo, it’s arguably much better at simply ensuring that almost no one can afford them.

That’s one credible answer to why more Americans aren’t having the sexual adventures they might like. Perhaps it’s already a lot to ask that so many women must convince themselves they’re riotously turned on by the same guy they want to have a beer with, or go to a museum with—or the one most able to help support their kids. It’s only practical to try to fetishize what seems to be your most manageable choice (though there’s something sick about requiring people to aspire to a state that’s designed to be settled for). Why waste energy figuring out what wild, inexpressible thing you might really want, when you know you’re unlikely ever to get it?

Witt writes that she’s spent much of her adulthood looking for alternatives that feel like more than “thinly veiled sales pitches,” finding them only in fleeting moments. You could take this as a sign that any desirable future sex can only be glimpsed in flashes, like God, or utopia. Yet it can’t be that there’s nothing between a depressing status quo and a 1960s wet dream—and the in-between is where Witt’s subtle gifts come into their own. What she sees out there is not as futuristic or as sexy as I’d hoped it would be, but then, narratively speaking, waiting for sexual or social utopia to just show up is not so different from expecting your dream man to deliver a sudden happy ending. Better to embark, as Witt does, on the occasionally dull or embarrassing work of finding out what small, concrete things you do desire, and to start making demands.

Lidija Haas is a writer in New York.