WHEN POPULAR FEMINIST writer Jessica Valenti was a prefeminist eighth grader in New York City, she left a crowded subway train one afternoon and realized that one of the back pockets of her jeans was wet. There was enough fluid that she worried someone would think she had “peed” herself, so she rushed home to take a scalding hot bath and hide the stain from her mom. Though she hadn’t noticed anything during the ride, she’s certain of what happened that day: A stranger ejaculated on her.

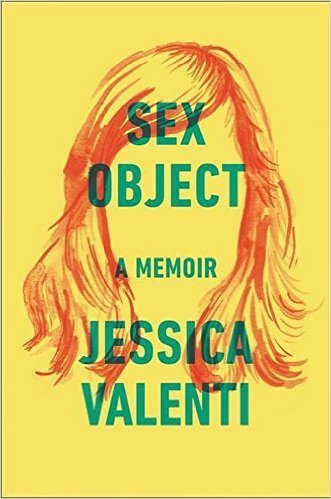

This bleak incident is one of many in Valenti’s latest book and first memoir, Sex Object, a work intended to illuminate the countless micro (and macro) aggressions endured by women at the hands of men. “Who would I be,” Valenti begins by asking, “if I didn’t live in a world that hated women?” The implied answer is: someone very different. Yet this is not the kind of memoir concerned with self-exploration. (Its rather baffling epigraph, taken from the mentally fragile protagonist of Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays, reads: “I am what I am. To look for reasons is beside the point.”) Valenti takes her problems to be problems all women share. “Object status is what ties me to so many others,” she writes in her introduction, adding that “those at the margins” have it much worse. She presents her life as evidence of what even a relatively lucky woman must navigate to survive our society: menacing strangers on the streets, cruel boyfriends in the sheets.

I don’t mean to be glib. It takes an especially disingenuous person to deny that sexual assault is commonplace, and yet for every woman with a story of violation, there is at least one man—and sometimes another woman—ready to call her a liar, a tease, or an oversensitive hysteric. The recent outcry over Donald Trump’s Access Hollywood recording, and the various accusations leveled against him, highlight a truth few women need highlighted: Our bodies are regularly treated as public property. There’s undeniable catharsis in sharing stories—as people have in the wake of these scandals—of being grabbed, groped, coerced, and raped. When so many similar accounts pile up, it discredits the corrosive idea that every male transgression is somehow the fault of the woman involved. It also helps repudiate the lie that sexual violence is the domain of a few bad men, rather than a matter of course for many who don’t see themselves that way. (Whether Trump’s boasts about assaulting women are or are not actually common among men in locker rooms has been a topic of heated debate—as if words were the primary concern.) But Sex Object relies on this accretive technique indiscriminately, conflating every leer, every mutually disrespectful relationship, every overture from a married man into one long parade of sexist slings and arrows. Seen through this lens, most men are aggressors and all women are victims. (“Unwillingness to be victims, even if we are,” Valenti writes, “doesn’t protect us, it just covers up the wreckage.”)

Sex Object is haphazardly organized, a nonchronological sequence of essays in which ideas are sometimes only loosely linked. One chapter concerns the avalanche of abuse and insult Valenti has weathered as a public figure; another is about her rape while unconscious at the home of a man with whom she’d previously had consensual sex. In “Candy Dish,” she moves from her first abortion to meeting the man who would become her husband to snorting Adderall at the private party celebrating her first book’s publication. In “Stages,” descriptions of her daughter’s first ballet recital and her own grade-school predilection for theater are preceded by a long passage about senior boys asking for her number when she was only twelve, and a junior-high peer demanding she pretend to fellate a lollipop. It’s not always obvious whether an event merits the dark tone in which it’s described. The story of those seniors flirting with Valenti and her seventh-grade friends concludes: “A girl with us that night ends up getting pregnant by one of these men; I’ll hear years later in high school that they maybe got married.” But how old was this girl when she got pregnant by that “man”? Some kids starting senior year in high school are only sixteen, so what exactly was their age difference—four years? Six? Did they indeed get married? Is the girl happy? Does she feel abused?

The anecdotes in Sex Object are almost all similarly terse and under-explained, as if the bare facts should be damning enough. When Valenti was eleven, she tells us, a childhood friend put his hand on her breast and she was paralyzed with confusion. When she was twelve, “the same year I saw my first penis on a New York City subway platform,” she “started to have trouble sleeping” and “felt sick all the time.” When she was seventeen, a former teacher in his thirties called to ask if she’d like to “hang out.” When she was in her twenties, on her way into the bathroom at a party for sex with her boyfriend, she accidentally slammed her finger in the door and then, despite the pain, allowed the sex to happen anyway. One after another these stories appear on the page, seemingly intended both to numb and to shock with their relentless evocation of the experience—repetitive, painful, mundane—of walking through the world in a woman’s body.

In too many cases, Valenti takes it for granted that an incident is a clear symptom of gender inequality. “It did not feel immediately wrong or abnormal for him to be saying these things to me,” She writes of a married friend who tells her he wants her, “because these are the things that men say.” We’re not told what exactly he said, or how it differed from what a married woman might say when trying to initiate an affair. “I cannot believe,” Valenti writes, “that so long after I first experienced a man making it clear that his desires trump my comfort, I still accept it.” Yet this comes after she’s already told him to stop and he’s apologized “profusely.” If he ever crossed the line again, she doesn’t say so. And a chapter on giving birth is strangely preoccupied with the shaving and exposure of her vulva by nurses before her C-section. Are readers supposed to believe the doctors wanted this done out of prurience, or simply to humiliate her?

The book’s dissonances may result in part from Valenti’s attempt to corral the messy, confusing, ambiguous stuff of memoir into a simple polemic. “I want to be unequivocal because my politics call for it,” she writes at one point. “By not doing so I am opening myself up to criticism on all sides.” No wonder, then, that in this book she seems so chronically unreflective: She’s trying to fashion her life’s narrative within the confines of a cause she imagines cannot withstand nuance. I agree with Valenti’s basic premise: Social norms are hostile to women and that hurts us. Individual men are sexist and they hurt us, too, both intentionally and unintentionally. But is it wrong that I crave more convincing examples of this than Valenti seems able to offer? Her stories about a college boyfriend so unusually prone to violence that he frightened even his fellow fraternity members don’t seem the most useful illustration of the everyday sexism ingrained in many men (and women). And it’s hard to summon much political outrage over the anonymous e-mail Valenti received that read: “Your book is silly. And you are silly.”

VALENTI COFOUNDED THE WEBSITE Feministing in 2004, and in my early twenties I couldn’t get enough of its righteous, newsy, easily digested takes on abortion, birth control, cosmetic surgery, and purity balls. I suspect that if I reread those mid-aughts entries now, I might find them symptomatic of a feminism that prioritized mainstream culture and middle-class women’s issues over the urgent concerns of women who were in prison, or impoverished, or trans, or black. Still, Feministing helped teach me that young women could be funny and vibrant while also being angry and uncompromising. I’m glad and grateful I had it. But Valenti, once known for her irreverence, now expressly rejects levity. She complains that today’s feminism “is largely grounded in using optimism and humor to undo the damage that sexism has wrought,” citing the jokes of Amy Schumer, the lyrics of Beyoncé, and the general trend of responding to male crudeness with mockery. “This sort of posturing,” she writes, “is a performance.”

As I read Sex Object, I recalled that troubling strain in the works of influential second-wave feminist thinkers like Susan Brownmiller, Andrea Dworkin, and Catharine MacKinnon: an insistence that men hate women unstintingly and, left unchecked, will attempt to destroy us each in turn. And I kept thinking of one of the most notorious antidotes to that dystopian depiction: Camille Paglia. She’s full of objectionable opinions, but, at their best, her provocations are exhilarating. In books like Sex, Art, and American Culture, she argued that to live in the social world is to assume risk, regardless of gender. “Sex,” she wrote, “like the city streets, would be risk-free only in a totalitarian regime.” When a man on the street makes a “vulgar remark” to a woman about her body, Paglia suggested, she could respond with her own verbal onslaught; there was no need for women to act like “melting sticks of butter.” Not every uncomfortable or upsetting interaction must be treated as an unspeakable aggression. Many critics have flattened Paglia’s message into pure rape apologism, but she identified a tendency that still plagues mainstream feminists like Valenti: an unwillingness to make distinctions between actions that are offensive, hostile, or intrusive and outright physical assault; a refusal to see that different acts may warrant different responses.

Valenti doesn’t use Sex Object as an explicit call to arms. She’s not advocating for a specific solution. But she does express frustration with law enforcement for not doing more when a man masturbates at home in front of his window while girls walk by, for not tracking down the man who called her over to his car and exposed his penis, for not arresting the man who took pictures of her friend’s mostly bare back while they were out in public one summer. It’s the epitome of cultivated feminine fragility, inextricably anchored to class and whiteness, to maintain that your personhood is violated when someone masturbates to pictures of—or for that matter, his memory of—your back in the sun; or that the mere sight of a man’s genitals should cause a girl serious harm and must result in his imprisonment. In a context of widespread police brutality and mass incarceration, Valenti’s tacit assumption that the full power of the state should be brought to bear in these situations alarms me much more than a naked penis could.

It’s true, of course, that street harassment, flashing, and the like sometimes signal the start of escalating intrusions or attacks. Male violence is most predictable in its unpredictability: Women have been murdered for saying no and beaten for saying nothing at all. But many men are not immune to the power of public shaming. In a viral video filmed this August, a woman berated a man she suspected of touching himself inside his pants, until he fled her subway train. And the international Hollaback! movement encourages everyone—not only women—to document harassment on a publicly viewable map.

We already know that men in the right demographic (like Trump, or Bill Clinton, or Roger Ailes) usually suffer little to no judicial consequence for their crimes. Meanwhile some of these same men—men so eager to proclaim their “respect” for women—support measures that keep less powerful men locked up for minor infractions. This formalized inequality is not unavoidable. It’s a state of affairs purposefully engineered to benefit the white and the rich—and, typically, the male. Participating in this system means playing by its rules. Valenti reflexively reaches out to the authorities about the aforementioned attacks on feminine respectability, and yet she doesn’t go to the police after her actual rape. I don’t blame her. I don’t know any woman who has—and I, like you, know a lot of women who have been raped (myself included). Most women recognize that when it comes to more serious assaults, the system isn’t designed to serve us. By rejecting the suggestion made by Paglia and others that we greet those who harass us in public with whatever response we choose—whether that’s mockery, public shaming, or a refusal to engage at all—Valenti dismisses what may be the only hope many women have of shaping their daily experience.

I’m regularly infuriated by what men will do and say to me and other women on the street—but then I also sometimes laugh in genuine amusement, or feel momentarily flattered by the right delivery. Twice, I’ve even dated (so to speak) men who struck up conversations with me on the sidewalk and in the subway. Cities are wellsprings of human collision, and the dynamics of their public spaces are nowhere near as predictable as Valenti’s book tends to suggest. I’ve seen a woman instigate a screaming match with a teenage busker, watched a man surreptitiously take pictures of two girls caressing each other, witnessed an older woman make increasingly explicit comments to a young man and delight in his discomfort. I’ve even sat on a dirty diaper someone left behind on a train bench. Some confrontations are more the result of sheer human density than of a pervasive masculine dominance. Women and gender-nonconforming individuals are more likely to be harassed in areas where pedestrian traffic is especially high, and presumably racist and other provocations are also more common in those places. (Valenti admits that when, as a girl, she ventured outside her home city to suburban and exurban areas, the din of male solicitation dropped to barely a whisper.)

In last year’s The Odd Woman and the City, Vivian Gornick, another memoirist and native New Yorker, had a very different take on entering the same fray. What Valenti meets with anger and exhaustion, Gornick, a lifelong flaneuse, mines for inspiration:

People who were strangers talking at one another, making one another laugh, cry out, crinkle up with pleasure, flash with anger. It was the boldness of gesture and expression everywhere that so captivated us: the stylish flirtation, the savvy exchange.

Of course, Gornick here is probably not thinking of a child leaving a subway with ejaculate on her jeans. But it’s hard to disregard her description of the bristling energy of urban environments, of lives converging and mixing in every exciting, unwelcome, and alarming way. There is no shielding participants from these unpredictable effects—even laws don’t really do the trick (and they have their unwelcome, alarming sides, too). A life without guarantees: Is this what freedom brings us? If you endeavor to be more than an object, it may be the only option.

Charlotte Shane is the author of the lyric memoirs Prostitute Laundry and N. B. (both TigerBee, 2015). She lives in New York City.