There was a moment soon after I moved to New York City from Oregon—though not that soon, maybe two years in, the point being how long my pristine naïveté resisted corruption—when I realized that every new literary person I met had gone to Harvard or Brown. I didn’t know why more of them hadn’t gone to Yale, Princeton, or Cornell (my new friends, with their firsthand understanding of the relative strengths of the Ivies, likely could have explained), but they hadn’t. These people had been, as a rule, editors of the Harvard Advocate or tutors at the Brown Writing Center, and when they graduated, they moved to Brooklyn, took internships at the New York Review of Books, and prepared to pitch magazines that had employed one of their relatives. I can think of an outlier who went to Rutgers, and another who went to the Honors College at Hunter, and I don’t mean to ignore the Columbia people or leave out the odd alum of Barnard or Bard, and it wasn’t that I never met a Yalie (is that the term?)—but in general the circles I traveled in were populated, as I began dimly to perceive, by people who had a great deal in common with one another.

My adopted cohort took the prestige of their educations for granted, and if, generally speaking, they were as insecure as the next person, the insecurity didn’t extend so far as to make them doubt the validity of their credentials. I can think of at least one guy who keeps his alma mater (“summa cum laude”) in his bio, eighteen years after graduation. My friends’ concern, as far as I could tell, was whether they measured up to the name of the institution, not what exactly the name measured. For my part, I was publicly unimpressed, privately envious, and, when it came to my own schooling, which had been at the University of Oregon, secretive. I wondered if I was ill-prepared to succeed (I needn’t have wondered: I was) and hoped that if I didn’t mention it no one would notice. I had moved to New York to get an MFA at Columbia, and as I warmed to that institution’s expensive embrace—as I learned to take for granted the program’s intimacy, for example, with major publishers and the cozy flock of agents they rely on—I understood something else. On the whole, my new friends had gone to certain colleges not because they were writers with special gifts—although they were—but because those gifts had been nurtured by families with certain resources.

I refrained from discussing my realization, because it is uncouth to talk too frankly about money to people who have it; it makes them feel self-conscious, guilty, and defensive, as if you are suggesting that they don’t have difficult lives filled with complex problems. And I saw that my friends had strong ethics about, say, not accepting help from their relatives, or which kinds of help it was acceptable to accept. (Direct deposit into bank account: no; down payment on purchase of apartment: yes.) They felt proud of making their own way in the world.

I also began to see how they were afflicted by subtle differences among their ranks. The Brown people had been wait-listed at Harvard; the Harvard people, as they began placing articles and selling books, nursed shame about who among them was quicker to publish or more celebrated. They could tell you who had gone to Exeter and who to Stuyvesant, whose parents were corporate lawyers and whose public defenders, who grew up on a golf course and who in a medium-size apartment in New Jersey. I, meanwhile, exploited a rule of class struggle: You may lump everyone who comes from more money than you into a monolithic bloc, dismiss their hardships, and, if you wish (one does wish), downgrade your opinion of their achievements by however much seems appropriate to account for the favors, tips, recommendations, opportunities, and inflows of cash without which their talents would not so easily have flourished. I got over my sense of exclusion, in other words, by being cruel about why others belonged. And for a while, I mourned the life I might have made had I had similar advantages. (“Why do people do what their parents do?” asked one of my Brown friends, a writer, whose mother is a writer, too. She really was mystified.)

The few writers I knew who hadn’t gone to fancy schools could be spotted because their careers were advancing more slowly, as mine was. I would have been so much better at everything, I thought, if I had been raised in a family with more money—until, in a feat of self-help, I began to insist to myself that the reverse was true. It was better to have come from less, I decided; it was both more interesting and undoubtedly purer to be poorer. I soon started applying these upside-down values to everything: I preferred dysfunctional organizations, friends who showed up late, skin with wrinkles, the unsuccessful, the awkward, the backward, the ill. The correctness of these renovated judgments seemed so clear, and I held to my new beliefs so doggedly, that I was surprised every time I encountered someone who didn’t agree, someone who professed to appreciate success, grace, timeliness, health.

The economic profile of my acquaintances had remained obscure to me for so long in part because of a certain cultural loophole that allows people of middling and greater privilege, especially those in the arts, to behave for a period in their twenties as if they are penniless—or, more accurately, as if they are classless, as if they have sprung fully formed into the world rather than emerged from specific socioeconomic circumstances. Some years ago, n+1 held a panel discussion about money and writing on the premise that it would be useful—personally but also, in a small way, politically—to discuss some hard numbers and unveil some of the accounting tricks by which social class functions. Keith Gessen, Chris Kraus, and a handful of others gathered in a loft and talked about how they came by the sums in their bank accounts. The figures themselves weren’t remarkable, as I recall (Kraus told us how much she’d bought and sold some real estate for; Gessen revealed his word rate at the New Yorker). What felt worthwhile was the performance of announcing the figures—the air of transgression that accompanied sharing with strangers something ordinarily kept private.

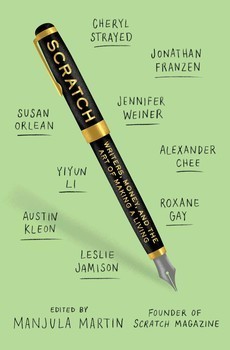

A similar impulse toward transparency motivates Scratch: Writers, Money, and the Art of Making a Living (Simon & Schuster, $16), an anthology of essays and interviews about writers’ relationships to money, edited by Manjula Martin. The contributors, who include Emily Gould, Leslie Jamison, and J. Robert Lennon, describe the work they’ve done for free, their first paid gig, how much they sold their first book for, what didn’t sell. (“I spent over a year trying to find a new agent for The Revolution of Every Day,” a writer I’ve never heard of tells us patiently about trying, and sometimes failing, to get her books published.) Running through the collection is an unmistakable thread of anxiety, of the sense of privation that comes from working in a narrowing field, and even the more famous writers—Cheryl Strayed, Susan Orlean, Jonathan Franzen—seem aware that they carve pieces from a shrinking pie. Yet the tone is by and large triumphal; everyone seems unnervingly grateful for what they’ve got. “Reader, I got the job. I’m going to be a teacher,” Nell Boeschenstein crows. With the first check Alexander Chee received for writing fiction, we learn, he bought moderately expensive bedding. The only real cry of pain comes from Jennifer Weiner, who must be one of the better paid of the bunch: She wanted love and all she got was money. How could the critics consider artistically “disposable” someone who, she is at pains to tell us, “graduated from Princeton with highest honors” and was accepted into the Ph.D. and MFA programs of “some excellent schools”? It’s funny that it’s the commercially successful, rather than those who don’t sell, who must remind us that money is no measure of value.

Chris Kraus stayed afloat by renting property; she was also, she told us during the n+1 panel, supported by her husband for some years. (If you’re going to take the dough, her argument went, don’t kid yourself by feeling bad about it.) Her honesty that night struck me, I think, because her disclosures weren’t some ritualized admission of privilege or of penury. She seemed not to be leaving out facts that might muddy the picture, like my freelancer friend who complains of indigence but fails to mention that he could always go live in his parents’ summer home. I know a writer in her thirties who still feels deprived because, by the standards of her Westchester high school, she was. Is it unhelpful to say that wealth is, inevitably, relative? Compared to my New York friends, I am poor and unlaureled, but among those I grew up with I am the person to envy. I want to tell you about my medical bills, the size of my debt, but what about my increasing cache of called-in favors, ill-deserved gifts?

Scratch and like efforts usefully destroy the fantasy that the production of a literary work is unconnected to its writer’s worldly circumstances. But—as I’ve determined over years of research in the field—no level of affluence will ensure that you write a worthwhile book. Consider the laws of the literary few: Having lots of money confers status but having very little confers legitimacy, which offers a different kind of status; having too much is unseemly yet so is having none. The rich and the poor collude in believing that the amount of money you inherit or make means something about your moral fiber, the quality of your art. What will we do when we find out it doesn’t?

Emily Cooke is a senior editor at Harper’s Magazine.