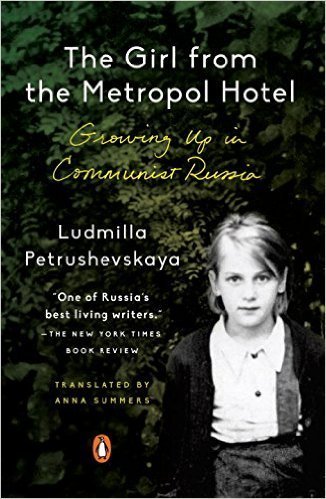

The fiction of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, one of Russia’s most celebrated living writers, can be divided into two categories. Her realistic work deals mostly with the lives of Soviet women, presenting a picture bleak enough that the stories were unpublishable in the USSR. In the US, Petrushevskaya is better known for the surreal, dystopian stories she describes as “real fairy tales.” Yet despite their fantastical elements, these stories, too, are grounded in Soviet reality: Their characters are preoccupied, as were citizens under Stalin, with food, housing, and violent death.

Petrushevskaya’s newly translated memoir of her childhood, The Girl from the Metropol Hotel, suggests that the “real fairy tales” are even closer to her lived experience than a reader (especially a non-Russian reader) might have imagined. As Keith Gessen and Anna Summers point out in the introduction to their translation of some of Petrushevskaya’s fantastical tales, many of them could be characterized as a trip to the underworld, a conversation with the dead like that found in Book XI of the Odyssey. Born in 1938, Petrushevskaya grew up amid Stalinist purges, starvation, and war, an atmosphere in which conversations with the dead would have felt familiar, even inevitable. It’s also clear that she learned very early how to lend both ordinary and frightening events the same sheen of magic, which may help explain her memoir’s oneiric chronology and fairy-tale archetypes.

Her mother, Valentina, came from a family of old-guard Bolsheviks. Several aunts and uncles fell victim to the purges and when Valentina, still a university student, became pregnant, Ludmilla’s father disowned the child in utero—he didn’t want to compromise his academic career with an accidental family of “enemies of the people.” Petrushevskaya’s first memories are of wartime Moscow, her mother carrying her to a bomb shelter in a metro station, the night sky crossed by light beams searching for enemy planes. “I remember not wanting to go underground,” she writes, “stretching my neck toward the festive sky, demanding to stay and watch the lights.” It’s an adventure, not a nightmare. Recalling her family’s evacuation from Moscow in a cattle car, Petrushevskaya emphasizes the cozy kettles boiling on a furnace procured by a fellow passenger. She remembers how, tucked inside her grandfather’s coyote coat, she imagined herself as a baby kangaroo. Her talents for storytelling and for living are unusually hard to disentangle. “Never have I been frightened by circumstances,” Petrushevskaya writes. “A little warmth, a little bread, my little ones with me, and life begins, happiness begins.”

This sunny outlook seems all the more remarkable as we learn more details of her childhood, some of which read as straight out of the Brothers Grimm. In Kuibyshev (now Samara), the town to which they were evacuated, Ludmilla, her aunt, and her grandmother lived in one room in a shared apartment. As relatives of enemies of the people, they were banished from the kitchen and had to cook on a Primus stove in their room, when they could afford the gas. At night, they scavenged in their neighbors’ garbage for potato peels, herring bones, and cabbage leaves. They were forbidden to use the communal bathroom, which was heated with firewood, so they bathed with cold water in their room. Breaking the house rules could mean death. “One night,” Petrushevskaya recalls, “we heard screams in the hallway. My poor old grandmother lay in a pool of blood outside the bathroom door.” A neighbor had caught the old lady in the bathroom and hit her on the head with the ax used to chop firewood. In this context, a story like Petrushevskaya’s “Revenge,” in which a woman in a communal apartment becomes obsessively jealous of her neighbor’s baby girl and plots to murder her, seems by no means far-fetched.

Some of the privations described in The Girl from the Metropol Hotel have a distinctly absurdist quality, such as the several years Petrushevskaya’s mother apparently spent living under a table. After returning to Moscow in 1947, nine-year-old Ludmilla moved into a single room occupied by her mother, Valentina, Valentina’s father, a brilliant, blacklisted linguist, and his wife, an evil-stepmother figure. Valentina initially made her daughter a bed on a trunk in the hallway outside but, when the stepmother had the trunk removed, Ludmilla joined her mother under the dinner table, where she had been sleeping since 1943. “It was our little home,” Petrushevskaya writes, with characteristic equanimity. “On the table, we kept utensils and foodstuffs; underneath, around the mattress, our clothes were piled up.” The stepmother soon had the table taken away, too, as Ludmilla clung to its leg.

Though both her parents were still alive, Ludmilla often told people she was an orphan, with some justification: Her mother was always leaving her behind or sending her away to summer camps and boarding schools in an effort to socialize the incorrigible child. Ludmilla also sometimes ran away herself, beginning at age seven in Kuibyshev, where she was for a while homeless. She had to compete with other street children for the bread crusts guards threw onto hot metal roofs at the Officers’ Club to distract pigeons; she befriended a stray dog, but the two of them soon parted ways over a bloody bone found in the gutter. It’s not surprising, then, that many of her fictional characters are orphans who manage to survive against the odds. In “Hygiene,” for example, a little girl, locked in her bedroom and left for dead during a plague, is, along with her cat, the only survivor in her building; her parents and grandparents, who had been feeding her through a hole in the door, are reduced to “black mounds.” Her mother had been infuriated by the girl’s insistence on treating the cat as a pet—”You’re feeding her what I tear out of my mouth to give to you!”—especially since the family had only taken in the stray animal for its “fresh, vitamin-rich meat.”

In fairy tales, of course, it’s often the young girls themselves who are at risk of being devoured. The protagonist of Petrushevskaya’s “The Shadow Life,” a girl raised by her grandmother, barely escapes being raped and murdered on a dark street by a group of men (she’s rescued by a vaguely magical couple). In real life, the preadolescent Ludmilla—who’d been locked inside for her protection but climbed, catlike, out the window—narrowly avoided being “passed around behind the sheds” by the local boys. Later, she evaded some neighbors in the prostitutes’ quarter in Moscow who were plotting to sell her virginity for fourteen thousand rubles. She also eluded a boy nicknamed “Gorilla,” and outwitted a group of classmates who surrounded her in a forest, hoping to “initiate” her. A preternaturally nimble and resourceful heroine, she keeps emerging unscathed. As Petrushevskaya puts it, “The circle of animal faces. . . never crushed the girl; it remained behind, among the tall trees of the park, in the enchanted kingdom of wild berries.” Dangers that in reality seem to have been the rule rather than the exception are here disarmed and, for good measure, frosted with fairy dust.

Like many memoirs of the Stalinist period, Petrushevskaya’s stresses the redemptive power of art. One of her brightest memories is of being allowed into the warm technician’s booth at the Kuibyshev opera house and watching Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, performed by the evacuated Bolshoi Theater. Pressing her ear to a boarded-up door in her family’s room, she memorized two classical pieces that played again and again on a neighbor’s gramophone. (He had only one record.) And Ludmilla’s grandmother—who had been courted, in her youth, by the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky—could reproduce Russian literature word

for word:

Our usual position was in bed, Granny towering over my bone-thin body like a mountain—so swollen from hunger was she. We covered ourselves with every rag we owned, and for days on end she recited classics from memory, primarily Gogol…. She had one weakness: she lavished too much attention on the descriptions of meals and innocently inserted mysterious items like borscht and bacon.

Art offered Petrushevskaya literal as well as figurative salvation: Like the young Édith Piaf, she used songs and stories to survive during her time as a street urchin. She would sing the two pieces from her neighbor’s record. If listeners were still interested, she’d recite one of her grandmother’s favorite Gogol stories, “The Portrait,” in which an impoverished young artist buys a cheap painting that magically guarantees him wealth and success but, as he discovers too late, deprives him of his talent. Petrushevskaya tells us that the story’s lesson remained with her for the rest of her life, but in the short term it earned her spare change, the occasional slice of black bread, and, on one miraculous occasion, a green sweater.

Her memoir has the fairy-tale ending its plucky heroine deserves. She graduates from journalism school, specializing in humor writing, and joins other students on a trip to northern Kazakhstan to work as a laborer and learn about the lives of “the people.” There, she meets the Moscow journalists who launch her literary career. We already know she’ll become a famous writer, but may not have guessed that, in her sixties, Petrushevskaya will start a second career as a cabaret singer. Writers of fiction can afford not to draw too sharp a line between the realistic and the fantastical—not every memoirist is so lucky, or so deft. Petrushevskaya is blessed with good material, but it also helps that she was teaching herself how to reinvent it before she could walk.

Sophie Pinkham‘s book Black Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine was recently published by Norton.