Among the iconic Hollywood Westerns of the 1950s, High Noon, with Gary Cooper as Marshal Will Kane, remains a classic movie in the most basic sense. More people know what it is than have seen it. High Noon has, in many ways, been reduced to one black-and-white image: Gary Cooper walking down an empty western street, wearing his badge, ready to draw his gun and face his enemies alone. In 1989 this film still was used, with an added red splash, as the campaign poster for Poland’s Solidarity movement, Cooper-as-icon standing in for the trade-unionist Lech Wałęsa in his quest to become the country’s first post-communist president.

In the US, however, John Wayne long ago overshadowed Cooper as America’s heroic ideal of the West. Wayne did great, enduring work in the films of John Ford, lived eighteen years longer than Cooper (who died in 1961), and appeared in nearly thirty movies during that time. But Wayne replaced Cooper as an icon for other, better-known reasons, too, not least because he was so politically contentious, so quick on the draw as a right-winger. In the competition for mythic identity and meaning, the anti-communist, Red-baiting, hippie-hating John Wayne won, leaving Gary Cooper in the dust.

Wayne, in fact, actively participated in this semi-erasure. He disparaged High Noon for years after Cooper’s death, even though, in 1953, at Cooper’s request, he had gone onstage to accept Cooper’s Best Actor Oscar for the film while Cooper was working on location. Wayne’s speech at the Oscars praised Cooper, and he said he wished he had played the lead in High Noon himself, but even then, in private and in later interviews, Wayne said the movie offended him. With its stark portrait of a lawman abandoned by his townspeople, the movie raised issues of loyalty and authority during the time of the Red Scare. Wayne considered it the work of communist traitors. Desperation, cowardice, asking for help to defeat a common enemy—these themes troubled Wayne as an American. He saw High Noon‘s exploration of them as evidence of weakness and subversion. In 1959, seven years after High Noon came out but more than a year before the blacklist ended, Wayne and director Howard Hawks issued a response to it in the form of another movie. In Rio Bravo, Hawks’s ideological undoing of High Noon, Wayne played a counter-Kane, a sheriff who does not ask for help in his standoff against bad hombres. Almost against his will, he draws the most stalwart people in town to help him do what’s right. Even the useless town drunk is redeemed, transformed from High Noon‘s shabby Jack Elam into Rio Bravo‘s appealing Dean Martin.

Rio Bravo is a celebration of camaraderie in the face of danger, like Hawks’s films in general. It rejects bitterness and disappointment, feelings Hawks kept at arm’s length throughout his career. Hawks was a more skillful director, and a greater artist, than Fred Zinnemann, the director of High Noon. The film critic Andrew Sarris accused Zinnemann of “making antimovies for antimoviegoers,” of being unable to “risk the ridiculous” to get to the sublime. The popular success of Rio Bravo and another, lesser Wayne vehicle, North to Alaska, in 1960, had the side effect of turning many subsequent Hollywood Westerns into corny romps: overlit, all-star celebrations of rowdiness in which chairs splinter over heads with little pain or consequence. Rio Bravo‘s lighter touch may have added to its artistry for cinephiles, but in the Hollywood Westerns that followed it, the ridiculous routed the sublime. While Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), also with Wayne, is a notable exception, it took Italian Westerns, which drew specifically on High Noon, to keep the genre from triviality. When Sam Peckinpah emerged with The Wild Bunch in 1969 and revised Hollywood Westerns for the Vietnam era, the genre returned to its dark core. Such films might have been made in America sooner if not for the blacklist.

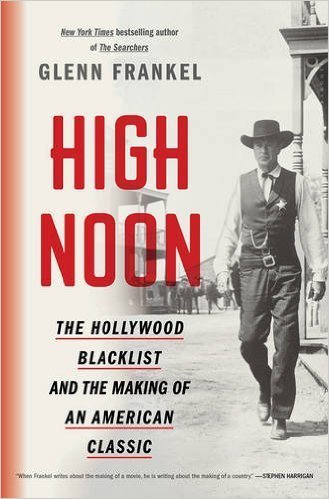

Glenn Frankel, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who has written books on Israel, South Africa, and another iconic dark 1950s Western, John Ford’s The Searchers (which also starred John Wayne), has now given us a production history of High Noon that is not far removed from a James Ellroy novel. The 1950s film industry portrayed in High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic is, like Ellroy’s Los Angeles, stocked with hard-core commies, idealistic fellow travelers, paranoid Red-baiters, union busters, corrupt congressmen, power-hungry gossip columnists, secretive FBI agents and their snitches, philandering actors and eager starlets. But far from being a Hollywood Babylon of the Red Scare, Frankel’s book is a detailed investigation of the way anti-communist persecution poisoned the atmosphere around one film, which succeeded nonetheless, and damaged the lives of the people who made it.

The book’s twin heroes are High Noon‘s screenwriter, Carl Foreman, and Gary Cooper. Foreman, named as a communist by a jealous screenwriter before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) on live TV, saw his friends and colleagues desert him during the production of High Noon, with the exception of one person. Cooper—fading movie star in ill health, wealthy socialite and celebrity, staunch Republican, cheating husband, lead actor in the infamous screen adaptation of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead—stood up for a man who was his polar opposite because he thought he was talented and getting a raw deal. In the paranoid context of Hollywood at the time, Cooper’s behavior was unexpected. Maybe he was too big to care at that point, but he did it pretty much like he was acting in one of his Frank Capra movies.

The connection between Cooper in the movie and in real life is apparent, so Frankel does not have to overplay it. It’s obvious that Cooper and Foreman’s personal lives somehow doubled the film’s story after Cooper was cast in the lead. Foreman stood up to HUAC and Stanley Kramer (High Noon‘s producer), then exiled himself to London so he could continue working. Just as Kane hesitantly confronted the outlaw gang in the movie, Cooper reluctantly backed Foreman at great potential risk to his career, which Frankel suggests he had stopped believing in anyway.

Cooper went so far as to start a production company with Foreman after he was called by HUAC. (The company failed to get off the ground before Foreman had to leave the US.) When Cooper’s marshal in High Noon tosses his tin star to the ground and leaves town at the end of the film, the scene and gesture seem to encapsulate both men’s careers in Hollywood. In truth, Cooper was no hero. “Darkness and doubt just followed him about,” as the Mekons sang about John Wayne. Frankel relates how Cooper beat up Patricia Neal, his Fountainhead costar and mistress, after he found her in a clinch with Kirk Douglas. And Cooper came and went in various right-wing organizations, not just the Motion Picture Alliance. One, an armed “paramilitary polo club” called the Hollywood Hussars, drilled under the supervision of ex-Army officers and active-duty cops.

A pox lies dormant in American politics, like shingles, and it has broken out again. The Trump administration, even before taking power, began to request lists of government employees who might disagree with its policies on climate change, gender equality, and anti-terrorism; a right-wing website is compiling a watch list of professors it accuses of liberal bias. Frankel’s book makes clear how volatile and destructive such lists can become, and the kind of people they empower. Here we meet men like the New Jersey congressman J. Parnell Thomas, an anti–New Dealer and Red-baiter who was chairman of HUAC but was arrested for common fraud and ended up in the same prison as some of the Hollywood screenwriters he hounded out of work. Then there is Richard Arens, staff director of HUAC, a “paid consultant for a shadowy and racist pro-eugenics group known as the Pioneer Fund” who warned that the fight against communism was “a total war, a political war, . . . a diplomatic war, a global war, . . . a war that they and not us are winning internationally and domestically at an alarming rate.”

As such men return to government now, it is interesting to remember what the blacklisted writer-director Abraham Polonsky said about his fellow communists in the film industry: “The Communist Party was for years the best social club in Hollywood. You’d meet a lot of interesting people, there were parties, and it created a nice social atmosphere.” Despite their bonhomie, they were outmaneuvered by the stupid and venal men who made up HUAC and by the press that supported it—the Chicago Tribune ran stories with headlines like “Politically Infantile Film Folk Were Easy Marks for Reds,” and the New York Herald Tribune‘s “Red Underground” column outed fellow travelers once a week.

As Frankel points out when he invokes Thom Andersen and Noël Burch’s 1996 documentary, Red Hollywood, it is a myth that the work of the blacklistees was inconsequential, despite what viewers may have gleaned last year from Hail, Caesar!, the Coen brothers’ comedy of 1950s Hollywood. Foreman survived the blacklist, cowriting The Bridge on the River Kwai for David Lean while in exile in London. He got no on-screen credit, which instead went to Pierre Boulle, who wrote the novel, had nothing to do with writing the script, and did not speak English. When the screenplay won the Oscar in 1958, Boulle, according to legend, collected it onstage, delivering the shortest speech in Academy history: “Merci.”

Frankel includes another odd scene in his book, in which Hedda Hopper, the vicious anti-communist gossip columnist, meets with Foreman in a London hotel in the mid-1950s after working so hard to destroy his career. She was in her sixties, he in his forties, but they found themselves attracted to each other. They polished off a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and stopped just short of making out. Politics makes strange bedfellows, people rise to some occasions and fail in others. As our new era unfolds, with the explicit promise, or threat, to make America as great as these 1950s again, we will soon find out if the bizarre tales in Frankel’s book will be repeated with a new cast of actors and writers.

A. S. Hamrah is the film critic at n+1 and writes for a variety of publications, including Cineaste and The Baffler.