Americans love their nostalgic cultural icons more than God and country. As our faith in every cherished institution from religion to the free press to science to democracy erodes before our eyes, our belief in The Force grows stronger by the day. “Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter!” we remind each other in yoga classes and Cineplexes and Comic-Con lines and also, probably, in bed. But why wouldn’t we prefer a devil-may-care space smuggler and a sassy princess to the citizens of the real world—preachers and teachers and scientists and diplomats and journalists? Who wouldn’t choose smoothly scripted Hollywood one-liners over depressing facts or vengeful psalms or complicated international peace treaties? Who doesn’t prefer charming vagaries to rigid doctrines or complex sociopolitical tracts? Why not throw out decades of painstaking, hard-won global nuclear-disarmament measures (just for example!) for the sake of a single, jaunty, pro-nuke tweet?

The imaginary universe, unencumbered by facts and ethics and diplomacy, is so much more fun and freewheeling than reality. In that fantasy world, valiant heroes die right after they deliver the plans that reveal the Death Star’s secret weakness to the rebel forces, thereby saving the galaxy from fascism. But in the real world, valiant heroes die as they eat soup, as they hail a cab, as they’re sleeping, as their planes land, right after their last book is published and a year before their final movie premieres, and fascism creeps into the edges of the frame without fanfare.

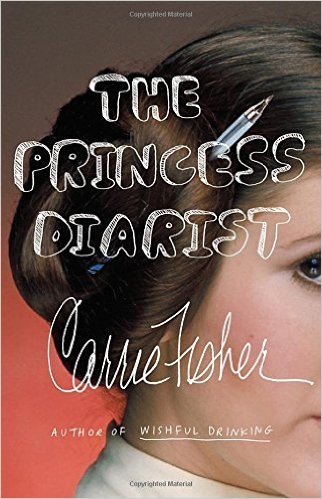

Strangely enough, this disconnect between fantasy and reality is what Carrie Fisher’s final memoir, The Princess Diarist (Blue Rider Press, $26), is all about. But then, few people knew how it felt to represent something hopelessly romantic and 100 percent fictional as well as Carrie Fisher did. And as an intelligent, complex, opinionated woman who struggled with addiction and a bipolar diagnosis, Fisher (who died of a heart attack in December at the age of sixty) didn’t always feel up to the task of representing the world’s favorite intergalactic princess. Because, in contrast to George Lucas’s nebulous fantasy world, which replaces inconvenient and displeasing facts with cool robots and pretty explosions, the arc of the real world, Fisher discovered, bends toward longing, unrequited love, funny-looking dogs, and seriously long-winded fan boys.

One drawback to the deluge of unfettered praise that follows any unexpected celebrity death is that it can be difficult to separate our nostalgic fantasies from the human being onto whom we project them. After all, Princess Leia formed a whole generation’s notion of female power and sexuality. Adorable, Disney-worthy title aside, Leia was not just another cutie singing and flouncing around a space palace, nor was she your stereotypical, skin-deep “strong” female character, replete with smart-lady glasses and an AK-47. Rather, Fisher’s Leia served as a talisman of casual, post-patriarchal female arrogance. Even though her character was very young and mostly wore white, she wasn’t remotely virginal, her tone of voice was the auditory equivalent of an eye roll, and she never hesitated to inform Darth Vader that he was wretched and vile, and to tell his henchmen that they stank to high heaven.

But it wasn’t just the Dark Side that put Princess Leia off her lunch. She was palpably underwhelmed by all the men she encountered, be they swaggering scoundrels or naïve farm-boy dreamers who were “a little short for a stormtrooper.” Leia didn’t preen or flirt or even slow her roll for a quick red-hot romp on an ice planet. She was far too busy trying to save the damn galaxy. By treating the men around her like slow children, she became the only hope for aspiring condescending females worldwide. Even though she needed a little help to defeat her mean daddy—who doesn’t?—her expression told us that she expected to do most of the work by herself, whether that meant threatening a roomful of deplorables with a thermal detonator or strangling an unfathomably rich, corrupt, sexual-predator slug with the chain he used to enslave her.

Considering Princess Leia’s outsize importance to American culture, it’s not surprising that Fisher described being treated like something akin to the Virgin Mary everywhere she went. Star Wars fans asked to take selfies with her. They asked her to sign their flesh, then got her signature tattooed on their skin. They instructed her to write “Princess Leia” under her name, which is a little bit like forcing Jesus to write “The Son of God!” under his.

In spite of such recurring indignities, Fisher regularly traveled to conferences to autograph photos of herself wearing that famous metal bikini for long lines of Star Wars devotees. The money was too good to ignore, so she gave in and participated in what she eventually came to refer to as “lap dancing.”

Fisher was that unusual icon who didn’t mind insulting herself, her golden goose of a franchise, and anyone who could possibly care about either. She not only didn’t believe in her own mega-celebrity status, but experienced a kind of permanent confusion over the idea that people were invested in what she thought or said. (Which doesn’t mean she didn’t enjoy the attention; her Twitter feed is proof of that.) Star Wars fans sometimes seemed as foolish to Carrie Fisher as swashbuckling smuggler pilots seemed to Princess Leia. She may have traded in her pride for a few dollars or given in to a clandestine kiss in the engine room, but the whole thing never stopped striking her as bizarre.

The same might be said for her real-life affair with a then-married Harrison Ford during the filming of the first Star Wars movie, which Fisher describes for the first time in 138 of The Princess Diarist‘s 246 pages. Fisher admits that the couple barely knew each other and hardly talked over the course of the three-month affair (it sounds like Ford is a man of very few words, at least around Fisher). She resists the temptation to describe their physical relationship, beyond the fact that Ford later told her she was a terrible kisser back then. This lackluster summary nonetheless yields to page after page of adorably precocious despairing dispatches from Fisher’s diary, written while she and Ford were together:

That old familiar feeling of hopelessness. That vague sense of desperation; fighting not to lose something before you’ve decided what you’ve got. I must thank him someday for teaching me to be casual. I realize I’m not very adept at it yet, but given a certain amount of time I feel I could learn to act as though I wanted to be somewhere else, maybe even manage to look as though I was somewhere else. I can charm the birds out of everybody else’s trees but his. Vultures are difficult to charm unless you’re off somewhere rotting in the noonday sun. Casually rotting… a glib cadaver. I’m sorry it’s not Mark—it could’ve been. It should’ve been. It might’ve meant something. Maybe not much, but certainly more.

Such passages reveal Fisher as a force to be reckoned with, both on the page and in real life. Or as Ford put it as he said good-bye to her after his scenes in Star Wars had wrapped (which also marked the end of their affair), “You have the eyes of a doe and the balls of a samurai.” Fisher writes, “It’s the only thing he ever said to me that acknowledged any intimacy between us, and it was enough.”

Which is a great attitude to have about an ill-fated love affair—or about your strange, vertigo-inducing transition from little-known actress to international cultural icon. But is it really enough? Don’t we always want more than a few months in bed with a sexy but self-censoring pilot and a few dizzying rides on the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy? Don’t we want more than a long line of devoted but hopelessly talkative fans whose children wail things like “No! I want the other Leia, not the old one”? Don’t we want more than a wax statue of ourselves in Madame Tussauds, half-naked in a metal bikini, immortalized not as one of the deeply heroic, fully clothed saviors of the galaxy, but as a sad girl owned by a mega-rich slug overlord? And wouldn’t Fisher have been horrified to discover that the first news of her death to hit the internetwould feature that same half-naked photo of her as Jabba’s slave?

If there’s a moral to The Princess Diarist, it might be this: Being a cultural icon is a form of lifelong enslavement. But maybe Fisher was also daring us to believe in something beyond the soothing nostalgic fantasy that has so many of us in its thrall at this dark hour. (When asked what she would do with The Force if she could use it in real life, Fisher answered, “I would make Trump go away.”) Without The Force and without Fisher, we’re going to have to do what Princess Leia might’ve done: We’re going to have to ignore the sneering and the grabbing, the mean daddies and their henchmen, the seductions and the outright lies, and we’re going to have to fight like a girl, fight like a doe-eyed samurai, fight like we’ve never fought before. Nothing less will do. The galaxy is depending on us.

Heather Havrilesky is a columnist for New York magazine and the author of How to Be a Person in the World (Doubleday, 2016).