THE MORNING AFTER the election I met with Mickey Michaux Jr., a North Carolina Democratic state legislator in his mid-eighties who was recruited to politics by none other than Martin Luther King Jr. Michaux was surprisingly sanguine, the victory of Donald Trump a disappointment but not a complete shock. Having come of age in the South under Jim Crow, he has confronted worse.

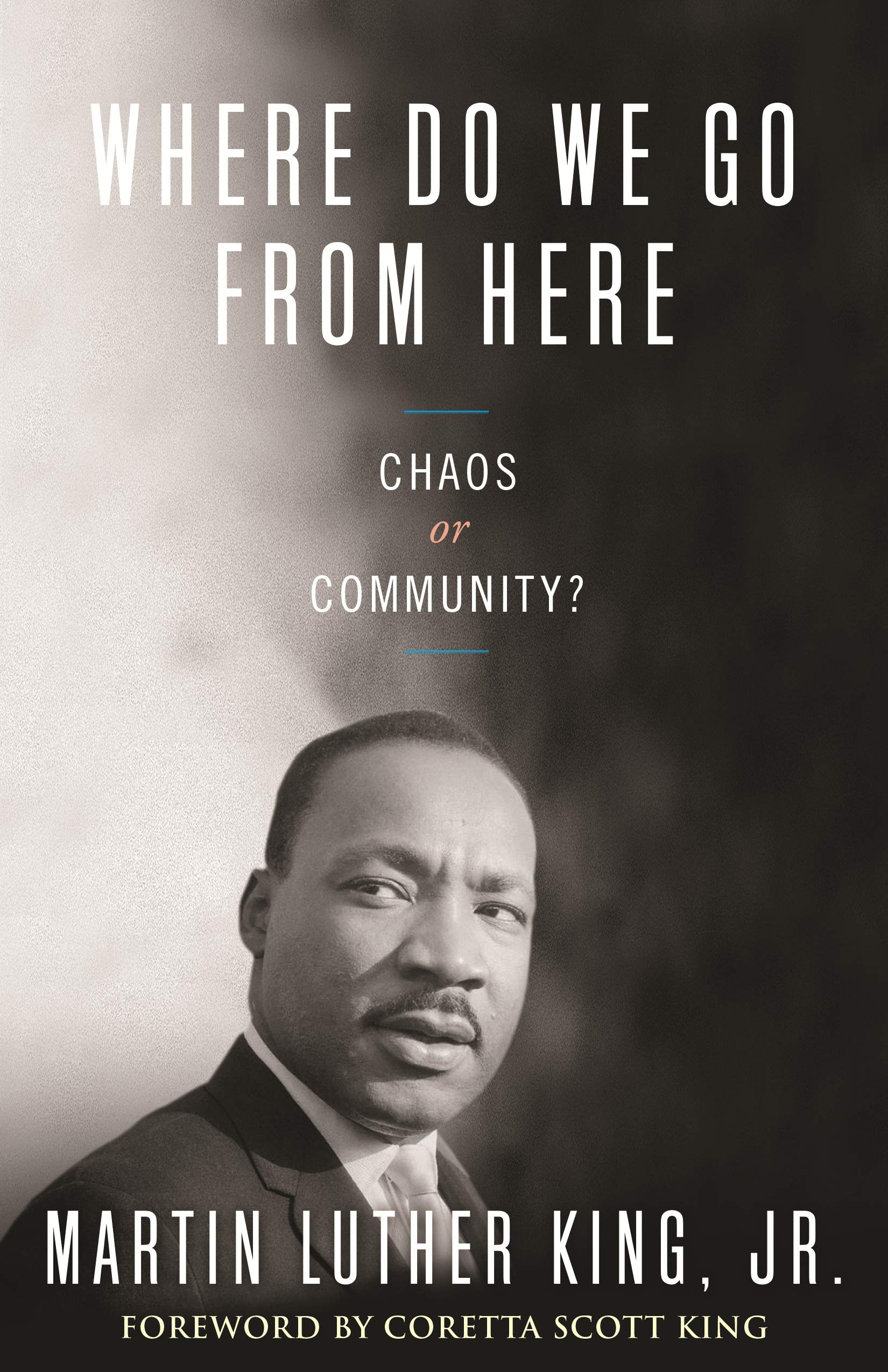

Michaux recommended King’s Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967), and said I’d find it prescient. He was right. The book is a searching assessment of the civil-rights movement, its victories and its weaknesses, written at a moment when progress was faltering or even sliding into reverse. King, however, rejects the newly popular concept of a “white backlash,” a term that has resurfaced in the aftermath of Trump’s election, preferring instead to underscore the fact that antidemocratic racism has been present since the nation’s founding. Racism, for King, is not a spontaneous response to calls for Black Power (just as today it is not a response to Black Lives Matter) but a pre-existing condition of American life, something we have yet to cure ourselves of.

To counter bigoted right-wing populism, King articulates a vision of “Power for Poor People,” an inclusive, multiracial movement rooted in economic solidarity and aimed at something that could be described as democratic socialism. King, of course, was assassinated before he could help manifest this vision. But it is an idea that is more relevant than ever, one we need to expand on and adapt for today.

Where Do We Go from Here is honest about just how hard it will be to win true social and economic justice. While the civil-rights movement has, understandably, been lionized and mythologized, King can be revealingly critical in his assessments in passages that today’s activists should learn from. He argues that the civil-rights movement had, to date, won only low-hanging fruit. “The practical cost of change for the nation up to this point has been cheap,” he writes. “There are no expenses, and no taxes are required, for Negroes to share lunch counters, libraries, parks, hotels and other facilities with whites.” Markets expanded as new, diverse consumers were brought into the fold. But moving forward, King predicts, progress will not be attainable at such bargain rates; the real sacrifice lay ahead: “Jobs are harder and costlier to create than voting rolls. The eradication of slums housing millions is complex far beyond integrating buses and lunch counters.” The things we are fighting for now—whether we are talking about closing prisons, instituting public health care, eliminating student debt, or combating climate change—demand investment and redistribution. They also mean a loss of revenue for the capitalist class, which partly explains why they are so difficult to win. As we can already see, Trump’s cabinet will further empower corporate elites, who will happily gut democracy and sacrifice a habitable planet to maintain profits.

As we enter into what I hope will be a long phase of anti-Trump street protests and resistance, King reminds us that we must do more than just declare our discontent. “Mass nonviolent demonstrations will not be enough. They must be supplemented by a continuing job of organization. To produce change, people must be organized to work together in units of power. These units may be political, as in the case of voters’ leagues and political parties; they may be economic, as in the case of groups of tenants who join forces to form a union, or groups of the unemployed and underemployed who organize to get jobs and better wages,” he writes. “This task is tedious, and lacks the drama of demonstrations, but it is necessary for meaningful results.” This tedious work was left unfinished half a century ago, but it must be picked up with renewed urgency and commitment. If it isn’t, King warns, chaos will be our destination.

Astra Taylor is a cofounder of the Debt Collective and is working on a film about democracy.