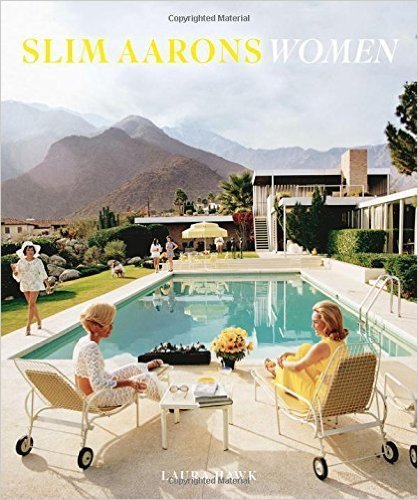

In the jet-set portrait extravaganza Slim Aarons: Women, the captions home in on a subject’s status like surface-to-air missiles:

Mrs. A. Atwater Kent Jr. (the former Hope Hewlett Parkhurst) at H. Loy Anderson’s pool, Palm Beach, circa 1955. A. Atwater Kent, her father-in-law, was the inventor who pioneered the home radio.

Lady Daphne Cameron sits on a tiger pelt in the trophy room of Laddie Sanford’s Palm Beach house, 1959.

The first lady of the Philippines, Imelda Romuáldez Marcos, the wife of President Ferdinand Marcos, in Manila, 1972.

Made between the 1950s and the ’90s, these photographs of “privileged and sporty” blue bloods and tanned arrivistes could be from a safari guidebook, shot in exotic aristo habitats like Bermuda, Jamaica, Pebble Beach, Palm Springs, Monte Carlo, Acapulco, and Capri. Aarons’s reputation as the premier high-society photographer of the mid-twentieth century rests on his ability to depict purely social creatures as almost zoological specimens: fierce lionesses, picturesque gazelles, demure rabbits, endearing deer.

Objectification? That was the whole idea: their calling card, their armor, their charm, their day job, and their raison d’être. (The Duchess of York calls a couple of American fellow travelers “walking wallets”—meant as a compliment.) Socialites, movie starlets, grandes dames, sugar baronesses, models, art collectors, and princesses all take their turn in the frame, corporeal billboards trumpeting whim, entitlement, and Life as Unlimited Charge Account.

Some of them appear to have been raised for the purpose. Here, a woman’s upbringing is described as if she were one of her parents’ world-famous thoroughbreds:

Marie Maude McKim in Central Park, New York, 1959. McKim, known as “Memsie,” was the eldest of the three daughters of Robert McKim and Lillian Bostwick. Her middle sister, Lilly Pulitzer, later became the legendary designer of preppy printed clothing. . . . And her youngest sister, Florence, nicknamed “Flossie,” became Mrs. Nelson Doubleday, wife of the noted publisher. Riding to the hounds was a big part of their childhood on the North Shore of Long Island. Marie Maude’s stepfather, Ogden Phipps, bred and raced some of the greatest equine champions of the twentieth century: Seabiscuit, Bold Ruler, and Secretariat, among others. Her mother’s steeplechase horses won the coveted Grand National race in Liverpool a remarkable eight times.

Others attained objet d’arthood the old-fashioned way, by marrying upward:

Prince and Princess Alexander von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingfurst in Tyrolean dress, high in the Austrian Alps, 1958. “I could have been a queen but I settled for being a princess,” the vivacious and witty Honeychile Wilder is said to have quipped shortly after her marriage to Prince Hohenlohe. Her not-so-veiled reference was to a previous dalliance she’d reportedly had with King Farouk of Egypt. The spirited showgirl from Georgia, known around the world as “Honeychile,” is said to have been the inspiration behind the Ian Fleming character Honeychile Rider in the novel Dr. No.

Princess Honeychile von Hohenlohe—never mind Fleming, these are the rarefied precincts of Jackie Collins by way of P. G. Wodehouse. (Speaking of Jackie, sister Joan reclines in these pages as a 1955 Liz Taylor knockoff, wearing a silky peignoir and clutching, naturally, a pink poodle.)

The volume presents a wide selection of the photographer’s published work and outtakes, originally done for magazines of calcified gentility like Holiday and Town & Country. Edited and written with sympathetic indulgence by Aarons’s former assistant Laura Hawk (Aarons died in 2006 at the age of eighty-nine), it follows his long-standing motto: “Attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.” Yet the prevailing mood winds up an awful lot closer to the last-call ballad that closes down John Cale’s album Paris 1919: “Where handsome creatures come to watch / The anaesthetic wearing off / Antarctica starts here.”

These elegant hideaways and opulent playgrounds are sunny, but you still feel the chill of icy constraint. The backgrounds are virtually interchangeable—impersonal framing devices for detached beauties sunbathing fastidiously or lounging in featherbeds or simply taking the wealth-infused air. The photo captioned “A party at the Kaufmann Desert House, designed by Richard Neutra, Palm Springs, 1970” packs as much chic alienationinto the frame as Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point. The outtakes, showing the photo’s blonde keynote figure with her hand on her hip and a sneer for a face, are a little terrifying. Wearing what looks like a two-piece tablecloth, with bare midriff and upswept hair that resembles an Escher sketch of an Alien embryo, she seems to be thinking: “I married a millionaire and all I got was an invitation to this fucking Neutra house.”

Aarons idolized the rich and well-connected, but not necessarily in the most flattering way. He came out of World War II as a combat photographer with an incorrigible streak—only being awarded a Purple Heart saved him from a court-martial for insubordination—and that probably accounts for both his taste for escapism and the hint of residual cynicism that pervades his whole impervious enterprise. His attractiontothelifestyles of the “beautiful people” evokes something of Warren Beatty’s hairdresser-seducer character George in Shampoo. (Aarons seems to have taken the debonair English actor David Niven for his personal template.) He gloried in his subjects’ ironclad insulation from the harsh, mundane aspects of life: Ministering to the wives of the rich and powerful, making them look and feel important rather than merely “good,” he courted them, diverted them, and held them at arm’s length, reveling in the ambivalence of being accepted by their world without being of it. (Aarons’s elite women are almost buttoned-up inversions of de Sade’s doms and subs—bondage queens whose pleasure and pain are sublimated into aggressively good taste and impeccable manners.)

In the midst of the minor stars, swank matrons, stiff debutantes, and fringe-dwelling nobility, there is a spread of photos from a party at Hugh Hefner’s original Chicago mansion; it looks like they were taken during an episode of his Playboy After Dark show, though whether there were television cameras present or not is perhaps a moot point. Dave Hickey called Hefner the Norman Rockwell of sex, and it’s fun to contrast Aarons’s aesthetic with the Playboy ideal of aspirational American hipness and quasi-liberation. The latter may be a long way from what you’d call real emancipation, but compared to the moated-castle air that hangs over Aarons’s usual models, Hef’s party does evince a modicum of spontaneity. At least there’s a hint of hedonism, and even some racial and social integration, whereas the Aarons women, having attained Alpine, Riefenstahlian-Olympian heights, are like marble statuary on display not in the Pantheon but a panopticon. Cultivating that veneer of comportment and “breeding” looks exhausting: leisure as hard labor. It’s not that everyone seemssecretly miserable, but that the weight of expectations and taboo is omnipresent. One false move, one slip into scandal, and it’s expulsion from paradise for you, sugar. Aarons suspends judgment, or perhaps more pertinently, suspends sentence—a ritual of mutual supplication and exchange involving bouquets, back-scratching, and hard currency.

When Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull appear, their bored insouciance suggests just how much life is otherwise missing from these pages. Whether it’s Her Serene Highness Tatiana Fürstin von Metternich-Winneburg or a fresh-faced Eva Gabor, Jackie Kennedy-then-Onassis or Esther Williams (that Hollywood swimming star parodied in the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar!, hugely popular then and barely remembered today), Babe Paley or Joan “Tiger” Morse (here designated a Warhol “gal pal”), Aarons’s women might be retro replicants who haven’t quite intuited their looming obsolescence. Interestingly, real stars like Marilyn Monroe (right as she was breaking out in 1950) and Audrey Hepburn are rather diminished: Monroe looking slightly strained, Hepburn severe in all black at a cocktail party, her red lipstick laid on a bit too thick.The little flashes of astringency in Aarons’s work arelikeflaresat the side of a road not taken—though it might also be a case of his being more drawn to breeding and power than Hollywood celebrity.

“His 1955 photograph of socialite C. Z. Guest poolside in Palm Beach . . . would capture the imagination of a generation and become the archetype for Slim’s female subjects,” Hawk writes. “By the end of his career in the early 1990s, however, he had photographed an array of women who played far more varied roles in society: ranchers, lawyers, poets, politicians, surgeons, historians, race car drivers, big game hunters, philanthropists, opera singers, designers, and royalty in their own right.” Hawk doesn’t mention the plantation owners in the West Indies or the colonial gentry in Kenya, photographed with ornamental tribespeople in the background—about half a step removed from slavery.

His strongest images are those of women not burdened by half a ton of social baggage. A lively photo of actress Dee Hartford sipping “a local drink called a pussyfoot” and the perfect shot of a lone sunbather in a rocky Arizona grotto provide a few moments of blessed relief from the relentless regiments of preppy ladies, whose pets and children all wear the same overbred, out-to-lunch expression. It’s less a case of “Nice Work If You Can Get It” than a nice inferno to visit—if Dante were a besotted tourist in a monogrammed shirt, dangling a Nikon camera, forever chasing people with too much damn time on their hands.

Howard Hampton is a frequent contributor to Artforum and Film Comment and the author of Born in Flames: Termite Dreams, Dialectical Fairy Tales, and Pop Apocalypses (Harvard University Press, 2007).