“IT WAS THE WORST OF TIMES, it was the worst of times,” I once tweeted years ago. An evergreen tweet, if ever there was one. All the old internet banalities have a certain pathos now; there were so many ways to say “all is lost” in 2016: “I can’t,” “no words,”sometimes just plain “2016.“

On November 9, I knew, not unlike on 9/11, that my life had changed for good. Though I found it impossible to write, I thought, perhaps, I could read. But I soon realized there was little I could take in: What would work and what wouldn’t seemed rooted in the most obscure internal algorithms.

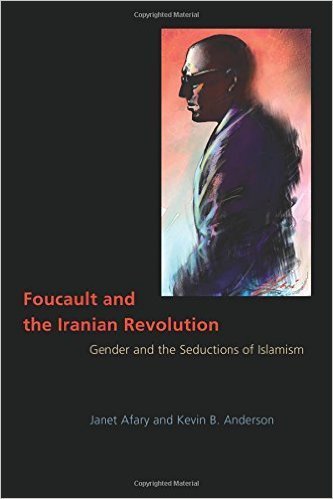

Three books did work for me, all for different reasons. The least likely was an ignored book about some forgotten Foucault: Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson’s Foucault and the Iranian Revolution: Gender and the Seductions of Islamism (2005). In 1978, Foucault was a correspondent for Corriere della Sera and Le Nouvel Observateur and he went to Iran, met with the Ayatollah Khomeini, wandered the streets of Tehran, and interviewed anyone he could, sort of casually rattling off some articles (published here along with context and analysis). Spoiler: Foucault was not so much pro-Islam as he was pro–Islamic Revolution, seeing something thrilling in the event that led my family and many other refugees to flee our homeland under abysmal circumstances. The book is a provocative testament of a genius who was a flawed journalist and even faultier political analyst. “What do you want?” Foucault asks everyone from students to religious leaders, often delighting in answers like “a utopia.” In the end, it’s an ode to Foucault’s almost eerie concept of “political spirituality”—government with a higher calling, if you will. Reading these selections provided me with some insight into ideological mobs on both the left and right—the intersection between Bernie Bros and Trumpkin Deplorables, for example—not to mention helpingput in perspective how other “radical” philosophers, like Slavoj Zizek, could prefer Trump to Clinton. In other words, it showed me just how our intellectuals can often fail us.

Have I mentioned it was the worst of times?

On the opposite end of the spectrum are Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (2004; reissued in 2016 in an updated edition) and Jesmyn Ward’s anthology The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race (2016). Solnit’s book was written during the Bush administration, just after the US had gone to war with Iraq, and one marvels at how fresh it still is. In a compelling treatise on optimism’s crucial role in activism, Solnit warns that if we give up and look away, we’re treating pessimism as prophecy. “The past is set in daylight, and it can become a torch we can carry into the night that is the future,” she writes in the introduction.

Meanwhile, Ward’s book—the title, of course, an apt echo of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time—is one of my favorite collections ever. Reading these writings—essays and poems and narrative nonfiction of all sorts—didn’t provide me with directives for action, but rather served an even more important function: reminding me that those of us on the margins are not alone. Dedicated to “Trayvon Martin and the many other black men, women, and children who have died and been denied justice for these last four hundred years,” the book explores black America’s past, present, and future, on topics ranging from urban mural art to Rachel Dolezal, from OutKast to Baldwin himself. It is not just story hour with writers like Claudia Rankine, Edwidge Danticat, Jericho Brown, Kiese Laymon, Mitchell S. Jackson, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, and Kevin Young; the descriptions and prescriptions by our greatest thinkers on race are a punch in the gut to every American. When the country chose racism over feminism on November 8, it wasn’t a new blow. The many isms and phobias of bigotry are not only the dark side of Americanism but also a defining element of America. Ward’s book doesn’t just say “Here we go again” but rather “Here we’ve been” and “Here we may remain,” if we don’t listen to the minorities who every day come closer to becoming the majority. Sometimes, the final words of Ward’s intro stay with me all day: “I burn, and I hope.”

2016: There were many futures to read ourselves into, but perhaps the ultimate consolation of Worst Times is thinking: “How much worse can it all get?”

Don’t answer that, 2017.

Porochista Khakpour is the author of the forthcoming memoir Sick (Harper Perennial, 2017) and the novels The Last Illusion (Bloomsbury, 2014) and Sons & Other Flammable Objects (Grove, 2007). She is currently writer-in-residence at Bard College.