Melissa Goldbach accused her child’s father of having sexually assaulted her during their custody handoff in a Wisconsin parking lot in 2011. When confronted with security footage of events different from those she described, she conceded that the sex had been consensual. In late 2013, North Carolinian Joanie Faircloth began to make numerous internet comments and social-media posts claiming that indie musician Conor Oberst had raped her when she was sixteen. After about six months, in a notarized recantation, she wrote: “I made up those lies.” “That part’s not true,” Carolyn Bryant Donham admitted over half a century after she’d claimed a stranger made verbal and physical advances toward her. The lie was told in Mississippi, in 1955, and the stranger was fourteen-year-old Emmett Till, who was subsequently lynched by Donham’s then-husband and his half brother.

It shouldn’t be outrageous to say that some women lie about sexual assault. Yet in pointing out the fact, I feel uneasy, a bit scandalized. Our shared narrative of rape tends to be that of grievous harm routinely inflicted by men (as a category) on women (as a category). For all its purported emphasis on consent, this framing is useless for understanding, say, male victims or female aggressors, and too rigid to offer much insight into power’s many mutable forms—it’s a spade where certain situations warrant a pair of tweezers. But nuance can feel dangerous in highly charged contexts: It’s not easy to acknowledge that a few women have made false accusations without appearing to imply that the rest should be disbelieved; nor to endorse self-defense training to protect against assault without seeming to lay blame on victims who aren’t sufficiently trained.

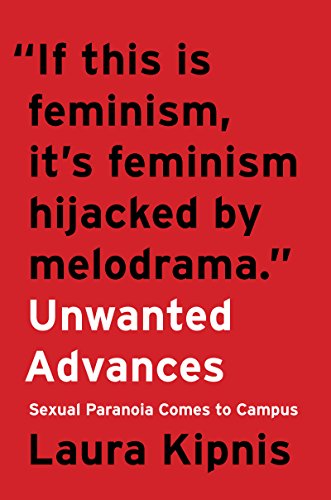

Luckily, this fraught terrain isn’t enough to scare off the formidable Laura Kipnis, and in Unwanted Advances she provides a wry, pragmatic analysis of the miscarriages of justice and abrogation of common sense sometimes perpetrated by American colleges in the name of protecting women. In case you’re unaware—though you probably aren’t, given the amount of press the subject receives—combating “rape culture” is a hugely popular campus cause, and Title IX, the law that prohibits gender discrimination in federally funded schools, is now habitually deployed as a corrective for alleged harassment and assault. (When I was in college, Title IX made news only in the context of athletics, but those days are long gone.) Kipnis, a feminist provocateur, cultural critic, and tenured professor at Northwestern University, is well positioned to report on the institutional quirks and conventions at play. Doubly so, since she herself was the target of a 2015 harassment complaint by two students (neither of whom she had taught or even met) who objected to something she’d written for the Chronicle of Higher Education. The offending article was a critical account of sexually paranoid and hyperreactive college environments. In a way, this happened to the ideal person: As Kipnis writes on the first page of Unwanted Advances, “I like irony.”

There’s even a meta-irony here. Kipnis thanks her accusers for inadvertently transforming her “from a harmless ironist into an aspiring whistleblower. High-flown terms like due process now spout from my cynic’s lips, as though principles really mattered and something should be done to save higher ed from its saviors.” Kipnis doesn’t seem the sort of enemy you’d want to attract, let alone help create. Her mind is too sharp and her sense of humor too robust; where others might blanch, she grins. Marshaling this enthusiasm, she handily identifies a number of interconnected problems. The first is that the so-called feminist framing of the issue of campus assault is “blatantly paternalistic,” wrong from the start, because relying on a classic woman-in-peril narrative is far more likely to harm women than to help them.The second is that this framing also employs a “rhetoric of emergency” designed to quash any seed of criticism of measures adopted to combat sexual assault.And third, that there’s been an unwarranted expansion of Title IX, which has been almost gleefully misapplied in recent years. What we now have is

a set of incomprehensible directives . . . being wielded in wildly idiosyncratic ways, according to the whims and biases of individual Title IX officers operating with no public scrutiny or accountability.

No one, Kipnis notes, seems to fully understand the requirements and limits of Title IX—not university presidents, not even Title IX officers. As far as Kipnis is concerned, college staff are regularly soliciting dubious allegations in order to suspend students and oust faculty from their jobs, all at a cost of millions. After she’s told she must meet with investigators without a lawyer present, to answer charges that will not be revealed to her until the meeting, she playfully compares the standard operating procedure of Title IX to that of the FBI, NSA, or CIA. The assumption seems to be that “you don’t need civil rights if you haven’t done anything wrong.” By focusing only on the potential power dynamic between professor and student, she points out, we miss the way in which this situation is “bolstering the power of administrations over faculty.” And, she adds, none of this appears to be reducing sexual assault. “The new campus codes aren’t preventing nonconsensual sex,” she writes, “they’re producing it.” If that strikes you as paranoid or extreme, you’ve probably never been on the wrong end of a Title IX claim.

Kipnis’s own Title IX “inquisition” is far from the worst detailed in Unwanted Advances, and hers at least had a happy ending: She was cleared of one set of charges, and the others were dropped. The original complaint was that Kipnis’s article had had a “chilling effect” on students’ willingness to report assault. In other words, it claimed that the exercise of Kipnis’s free speech would effectively impinge on that of others, and aimed to preempt this by limiting hers first. (Sound the irony siren here.) When the investigation ended, Kipnis writes, “I wondered if my investigators weren’t clearing me as much as they were shoring up Title IX.” Consider the avalanche of bad press that might have ensued if she’d been found in violation and lost her job simply for writing a thoroughly reasoned essay. (Unwanted Advances is, as you may have guessed, her stab at generating that bad press anyway. She writes of her experience sitting in on someone else’s dismissal hearing that “it’s not easy getting rid of a tenured professor at a major research university, or cheap, which is somewhat reassuring as I near completion of this book.”)

While it exposes how farcical the proceedings can be, Kipnis’s Title IX experience is otherwise anomalous, and the book’s other case studies tend to be more illuminating. Kipnis has access to the thick file of Peter Ludlow, a former professor at Northwestern who resigned after he was twice accused of sexual misconduct: once by a former undergrad, and once by a grad student whom he’d never taught or advised. Ludlow’s case is exceptional, in that he didn’t sign a confidentiality agreement on resignation, so he was free to show Kipnis the documents.

The greatest pleasure Unwanted Advances affords comes from Kipnis’s keen sense of human psychology. While clearly outraged by both the kangaroo-court antics of the Title IX officials and the pervasive myth of womanly helplessness they thrive on, she doesn’t romanticize the plight of the accused men and is often candid about her skeptical reactions to them and their stories. When she first meets Ludlow, for instance, she diagnoses him as follows:

[It] wasn’t that he played up his power so much as that he imagined he could play it down. He had a misplaced egalitarianism. . . . It’s not that he’s naïve about sexism or gender inequalities, though I suspect he thinks treating women as equals temporarily brackets the issue.

If you have spent any time in academia and are not nearly reeling from the accuracy of this description, I’d love to know the name of your school so that I can arrange to join you there.

Kipnis devotes a considerable portion of Unwanted Advances to the strange particulars of the accusation made against Ludlow by the former undergrad “Eunice Cho” and Northwestern’s handling of it. The ensuing web of lawsuits and retractions is far too complex and bizarre to outline here, but there are some especially confounding details. Complainants had the opportunity to respond to Ludlow’s version of events and drastically change their stories accordingly, while he was interrogated without being told exactly what had been said about him. The grad student who made the second complaint against Ludlow had had a months-long, heavily documented consensual relationship with him; only years later did she recast it as sexual misconduct on his part. (All of us, Kipnis concedes, are “free to change our minds about whether we did or did not love a previous paramour,” no matter how many thousands of affectionate text messages we may have sent at the time, but to bring in “an institutional apparatus and federal mandates to enforce your change of mind” seems quite another thing.)

Kipnis’s primary argument, based on the documents, is that the proceedings were guided less by the facts than by some very reactionary assumptions about femininity. Investigators applied the word grooming—a term for the process by which perpetrators of child sexual abuse prime their victims—to routine, innocuous academic practices, such as Ludlow’s offering the (twenty-five-year-old) grad student a travel grant during a student recruitment event, long before they became involved. And in comparing Ludlow’s story against Cho’s, they seem to have decided which details were accurate based on their own assumptions about what a man or woman would be likely to do. Anything Cho said that suggested Ludlow had been sexually aggressive seemed true, no matter how implausible, while even mundane details in Ludlow’s account—for instance, that Cho had asked if he was in a relationship while discussing her boyfriend—were rejected as unconvincing. By Kipnis’s account, those investigating the claims tended to minimize Cho’s agency to the point of erasure while depicting Ludlow as a scheming Svengali. As she puts it, “If Ludlow was capable of anything, Cho, by contrast, was incapable of anything.” Here, the usual gendered story, rather than common sense or critical thinking, sets the terms: Women are inevitably sexually weak and men are sexually strong, therefore “men need to be policed, women need to be protected.” And then there is the troubling insistence that only an institutional apparatus can perform the necessary woman-rescuing intervention.

Kipnis is disturbed by the strain of feminist campus activism that (like anti-porn feminism before it) seems eager to join forces with the government and the university to achieve its aims. It wasn’t always thus. She brags that her own generation wanted to “overthrow everything, especially the fucking administration”—and yes, that wordplay is probably intentional. College students are notoriously desperate to be free of supervision. So what motivates some to invite new authority figures into their lives just when they’ve finally gotten free of their parents? Kipnis believes it’s hysteria, spawned by the faux-feminist insistence that we are in an ongoing sexual crisis and that the consequences of even a mildly unpleasant or ambivalent sexual experience may be both dire and permanent. College women are encouraged to believe that “sex takes something away from you,” and that “you can catch trauma, which, like a virus, never goes away.” These bleak convictions are self-reinforcing. The more endangered you feel, the more responsibility you’re willing to forfeit. The more responsibility you forfeit, the less control you assume and the more fragile you feel. “If the prevailing story is that sex is dangerous,” Kipnis reasons, “sex is going to feel threatening more of the time.”

To that point, she includes quite a few examples of an ever-slipping bar for what passes as assault or harassment, such as a Title IX investigation of a grad student launched by an anonymous tip that he’d laughed too much at the phrase juicy Girl Scout during a card game held off campus. And in what truly seems like an invitation to further hysteria, Title IX complaints can be filed by third parties, so that students or officials are able to raise concerns about imagined wrongs inflicted on someone other than themselves. Kipnis illustrates the degree to which this can go awry with the story of a male student accused of assault after his sexual partner’s friend spotted a hickey on her neck. The hickey-receiving woman repeatedly confirmed that the sex was consensual, but the man was suspended anyway. Kipnis mentions that he was a black athlete, which could have been a factor in either the friend’s interpretation of events or the school’s insistence on penalizing him for his non-crime, or both. As the Ludlow case shows, prejudices about who is likely to be doing what can play an outsize role. Many straight men fall afoul of Title IX, but an anonymous professor also points out to Kipnis that queer faculty members are at particular risk of having their innocuous behavior, or their mere presence, misinterpreted. Title IX is so inconsistently implemented, it seems, that it’s wide open to abuse by just about anyone, be their motive racism, homophobia, jealousy, spite, or idle cruelty.

It’s possible, of course, that Ludlow’s case is not representative. It may simply have been handled with exceptional carelessness or incompetence. Yet if that were so, it would be nearly impossible to know. Title IX cases are secretive affairs, and very little cross-college data is collected. That secrecy applies even to those directly involved in a given case. “Typically,” Kipnis writes, “the accusee doesn’t know the precise charges, doesn’t know what the evidence is, and can’t confront witnesses. Many campuses don’t even allow the accusee to present a defense.” This sort of blindfolding, coupled with the Department of Education’s low standard of proof in Title IX cases, has led to an increasing number of legal challenges in non-college court. It may be that these verdicts will provide the impetus for change. While there must be many college officials acting in good faith, institutions are heavily incentivized to appear compliant with Title IX, lest their federal funding be denied. They may not rethink their current sloppy approaches unless there are even steeper financial consequences.

Overreach is not the only problem, and Kipnis makes clear her awareness of that fact. There are many instances of assault in which the system is guilty of neglect or obstruction. And one of the great challenges for feminism, as for any progressive movement, is knowing how to work with the tools at one’s disposal, no matter how crude. (A good example of the contortions this sometimes involves is the Roe v. Wade precedent that makes abortion an issue of privacy rather than of basic health.) Title IX is now making headlines for its relationship to trans students’ rights. Under Obama, it was used to require that colleges allow students to use bathrooms consistent with their gender identities, but the Trump administration has rescinded that guideline.

This reversal makes readily apparent why Title IX is such a flimsy stand-in for more durable commitments to justice for vulnerable students. The preferable alternative would be for schools to issue their own regulations as part of an empathetic, intelligent collective vision. Yet because such protections will be a long time coming, Title IX is currently as important as it is inadequate, and it would be difficult to argue for abandoning it altogether. Kipnis makes a sterling case that further “weaponizing Title IX” is not the solution to sexual assault. But that’s sure to be a hard sell for those who feel that without it, they have no weapon at all.

Charlotte Shane is the author of the lyric memoirs N. B. and Prostitute Laundry (both TigerBee, 2015).