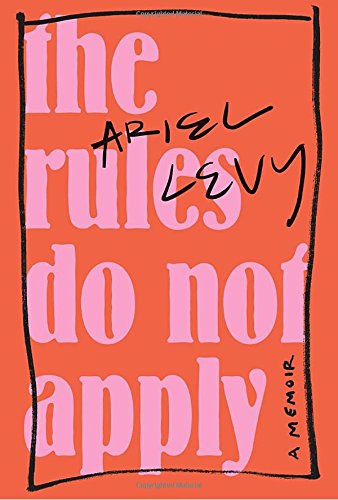

The debate about whether women can “have it all” has aged only slightly better than stock photos of women in skirt suits with babies on their hips. Yet the questions at the heart of that worn-out conversation are freshly animated in Ariel Levy’s new memoir, The Rules Do Not Apply. Levy defines “it all” as not simply “a career and a family,” but a woman’s ability to live her life exactly as she wants to. “We want a mate who feels like family and a lover who is exotic, surprising,” she writes. “We want to be youthful adventurers and middle-aged mothers. We want intimacy and autonomy, safety and stimulation, reassurance and novelty, coziness and thrills. But we can’t have it all.”

Levy, who has spent the past nine years chronicling the lives of extraordinary women (and some men) as a staff writer for the New Yorker, warns her readers up front that this is not a “you-go-girl” story about a woman who defies convention and ends up happier as a result. Levy has lost her pregnancy, her spouse, and her home in the span of just a few months. “The future I thought I was meticulously crafting for years has disappeared,” she writes in the preface, “and with it have gone my ideas about the kind of life I’d imagined I was due.” Of course, most of us expect to have to work hard in order to get the kind of life we want. The truth at the heart of Levy’s memoir, though, is that even the most privileged American women are not in total control of which desires will remain unfulfilled. And this can be an excruciating fact to accept.

For decades, cultural conservatives have warned that the promised freedoms of feminism come at too great a cost. While Levy’s book doesn’t purport to be anything broader than a personal “story of resilience,” she implicitly buys into the notion that women in her position have chosen to embrace their now-expansive options without acknowledging how their traditional desires conflict with the new things they want. Levy, though she plans to raise a baby with her female spouse, is frank about relishing the financial security and male attention that the baby’s father brings into her life. “To say that I was thankful for this security is to put it rather mildly,” she writes. And even though she is incredibly proud of her career, her pregnancy is validating on a much deeper level: “I was making something so good out of my very self—how rotten could I be?”

Levy’s own life tracks quite closely with the “having it all” timetable: Build a career in your twenties, land your dream job and find a mate by your early thirties, and have kids just before your fertility expires. Getting pregnant at thirty-eight, she writes, “felt like making it onto a plane the moment before the gate closes: You can’t help but thrill.” But of course, no personal narrative is that neat. Levy and her wife, “Lucy,” marry in a rather traditional ceremony, which Levy chronicles in a New York magazine essay that reveals her ambivalence: A photo of Levy accompanying the essay is captioned “The ‘bride’ in her Carolina Herrera dress.” Having it all, apparently, requires a few scare quotes.

Once she and Lucy have settled into their vacation home on New York’s Shelter Island, Levy embarks on an addictive affair with a former lover and comes to realize that Lucy is an alcoholic. After all that, they get their relationship back to what seems to be a stable place, and Levy gets pregnant. This is the peak of her happiness: In her own idiosyncratic way, she has followed the new path for women. Despite the title, a key theme of Levy’s work is that some rules do, in fact, apply, even if they’re rules you’ve made up for yourself. She feels like a witch who has conjured this ideal life. “It was like magic,” she writes.

Then, while on assignment in Mongolia, she goes into labor at five months pregnant and loses her child. The entire narrative collapses. “I had been so lucky,” she writes. “So little had truly gone wrong for me before that night on the bathroom floor. And I knew, as surely as I now knew that I wanted a child, that this change in fortune was my fault. . . . I was still a witch, but my powers were all gone.” The difficult thing about thinking you are free to choose whatever life you want is that, when you end up unhappy, you have only yourself to blame. Even if your doctor insists, as Levy’s does, that your choices had nothing to do with it.

She arrives home, grieving, and realizes that her wife is still drinking. The marriage unravels shortly thereafter:

It’s not a good feeling being right about something you have suspected when you finally gain undeniable confirmation that it’s true. It is not the satisfying sensation of everything slipping into place for which you have yearned. It’s more like, Oh, right. The man who has been staying over your whole life long is your mother’s lover. The reason Lucy seems off sometimes is that she’s still drinking. You have always known this. The only thing that’s mysterious is how you managed to think it mysterious.

This is perhaps why she described her happiness as magic: She always suspected it couldn’t last. Levy shows just how easy it is for women to interpret their misfortunes as punishment for making the wrong choice or wanting too much. We’ve been taught to expect bad things when we step out of bounds.

Coming to terms with the downside of making your own rules, Levy concludes, is not giving up. It’s growing up. And for those of us who expect that we can fulfill our every desire if we just work hard enough, experiencing the sort of heart-crushing pain that Levy has survived might be the only path to the other side, where the rules may still apply, but at least we can recognize them for what they are.

Ann Friedman is a columnist for nymag.com and cohost of the podcast Call Your Girlfriend.