In February, Amnesty International published a report on the Saydnaya Military Prison in Syria that made for especially gruesome reading. The headline revelation, that the Syrian authorities killed up to thirteen thousand people in extrajudicial executions at Saydnaya between 2011 and 2015, surprised exactly no one familiar with the structure of the Syrian state or the regime of Bashar al-Assad and its long-standing use of torture. Amnesty estimates that there are now up to twenty thousand detainees in Saydnaya, virtually all of them nonviolent demonstrators who never joined the Free Syrian Army or the Islamic State or any of the other factions now active in a war that began as a peaceful uprising. The report details mass hangings, policies of extermination, starvation—cruelties meted out to bystanders and noncombatants that are shocking in their severity and excess. Most disturbing are the clear historical echoes of death camps and the Holocaust, combined with the knowledge that these atrocities aren’t over. They are happening right now.

Saydnaya was a major news story for about a week in London (covered three times by The Guardian) and a day in New York (mentioned once on page A6 of the Times). Clearly, something is wrong when such a disturbing narrative barely makes a dent. No one can deny Amnesty’s good intentions, but it may be that the language of the report and its tone of moral indignation are no longer adequate to a conflict as reliably sensational and consistently brutal as the war in Syria. A sharper, more complex portrait of the situation emerges from the myriad other stories coming out of the country in studies, memoirs, investigative reports, and eyewitness testimonies. Perhaps most interesting are the artworks and experimental-publishing projects, both in print and online, that are drawing on the tools of activism, journalism, academia, and contemporary art to do something both useful and hopeful in the immediate context of the destruction of the country, its culture, and its people.

There is, of course, a long and complicated history of artists and writers using their work to respond to the extreme crises of their time, including war, famine, natural disaster, and economic collapse. Their reasons for engagement differ and often depend on the artists’ own proximity to danger: Some want to bring the world’s attention to their own city or country at risk of being destroyed. Others want to direct the world’s attention elsewhere, to a secret war or a conflict no one seems to know about. Still others are motivated by the need to bear witness. In all cases, there’s an incredible urgency to work, stay human, and remain capable of thinking in the face of unthinkable cruelty. Often, intellectuals are drawn to a cause even if they can’t or won’t fight, and they make their work with a complicated awareness of guilt and privilege. Almost always, the art made in direct response to a crisis is effective in its moment but embarrassing shortly after. And just as frequently, the critics get it wrong: Susan Sontag was ridiculed for staging Waiting for Godot in the middle of the siege of Sarajevo, even though she made her intentions remarkably clear. She wanted to prove that intervention would save a city that was very much alive, where art was thriving even in a war zone. Who is making that case about Syria today? Would it make any difference? We might learn more about the possibilities for justice and dignity in Syria by looking at the art of lesser-known figures who are working on the ground amid so much violence.

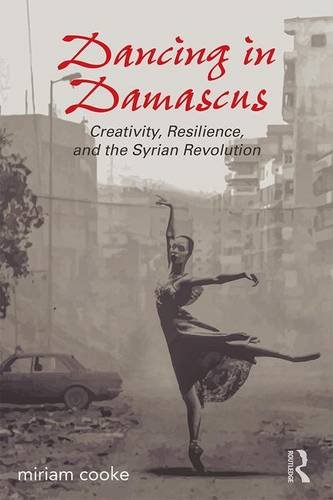

That, at least, is the premise that has been admirably taken up by the American academic miriam cooke (like bell hooks before her, she lowercases every letter in her name). Her unusual new book, Dancing in Damascus, captures something crucial about the initial Syrian uprising in 2011—which was nothing if not chaotic—and holds onto it. To imagine radical change: That is the spirit that cooke returns to again and again. Her book is a document of a lost time when unprecedented ambitions for a better life were suddenly being shouted in the streets, when unspeakable criticisms of the regime were suddenly articulated. Cooke writes about paintings, sculptures, caricature, refugee theater—and an awful lot of internet art that is mostly terrible, though who can be too sour as a critic under such circumstances? She gives equal treatment to short-lived, ephemeral Facebook groups and more established platforms like Abounaddara, the ambitious and mercurial collective of anonymous Syrian filmmakers that has been posting short, powerful videos online, every Friday, since 2010.

Cooke is uniquely positioned to make something of her slim volume. Thirty years ago, she wrote an influential study of women’s literature in the Lebanese civil war, coining the term Beirut Decentrists to describe the novels of Hanan al-Shaykh, Ghada Samman, Etel Adnan, and others who fractured the political narrative of the conflict into shards of lived experience. In the 1990s, cooke turned her attention to the co-optation of dissident Syrian intellectuals under the reign of Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez al-Assad. So she is particularly well suited to place the art of the current conflict in a larger narrative about artists and writers responding to war and pushing back against the Syrian regime. She situates today’s tentative performers and young artists in search of an audience in a lineage that reaches back to the 1970s, showing that artists in Syria have long been producing their work in a coded language. In the art of the revolutionary era, artists such as Tammam Azzam have steeped that language in black humor and irony. Azzam’s digital collages layer art-historical masterpieces over what can only be described as war porn. The joyous red bodies of Henri Matisse’s dancers, for example, are superimposed on a photograph of the rubble of destroyed buildings. For cooke, this adds up to a wobbly theory of transactive art. Because viewers must actively decode this work, they must fully engage with it. The work thus stimulates critical thinking, a process that will actually bring the revolution to fruition and the war to an end.

The problem is that much of this work cycles through the same images of violence that the regime itself is constantly producing. There is a fine line between exposing violence and becoming trapped by it. The majority of the art in Dancing in Damascus doesn’t go beyond the horror, doesn’t find something else to say or do. Cooke convincingly demonstrates that artists have stepped into the void left behind by journalists who were barred entry, kidnapped, or killed, and that they have found innovative ways to show the war in artistic terms. Less convincing, however, is her notion that the revolution will win on the strength of the art she writes about—even if it does foster critical engagement. To defy and to document is one thing. To imagine a new country—what happens next, what a different system of government would be, how people will return to peaceful living—is quite another.

To find work that is faithful to the enormity of the conflict but transcends its brutality, one must look to artists who are working beyond the scope of cooke’s study. Perhaps because she focused on the artistic equivalent of first responders, cooke omits a newly emerging, fascinating body of work: complex projects created at a slight remove, where artists living in exile or operating just outside of the crisis are trying to do two things at once—to build physical or digital objects with the capacity to change the conditions of the conflict in practical and discursive terms, and to reclaim a sense of wonder and enchantment for art in relation to Syria, despite the horror. These projects find artists doing the storytelling work of writers and presenting narratives in bold new ways, asking questions about what stories can offer in times of crisis. And they go beyond simply raising awareness or defying the murderous regime. They address the concrete needs of the war’s survivors, situating the crisis in a historical context while also balancing practical concerns with loftier artistic gestures. In other words, these projects are a way to help out, and a reminder to Syrians that they speak the language of a rich and complex heritage. They have not been reduced to mute trauma.

One of the most interesting such projects is the work of a young artist, architect, and aspiring art historian from Damascus named Khaled Malas. Three years ago, he was invited by his former boss Rem Koolhaas to propose an idea for an unofficial, non-state-sponsored Syrian pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale. Malas decided to undertake a project far off-site. He teamed up with a small group of activists in Deraa, the town on the Jordanian border where the Syrian uprising began, to build two secret wells for a community of twenty-five thousand people. Titled Excavating the Sky, this was the first installment in a series called “Monuments of the Everyday,” for which Malas, now working collectively with the group Sigil, uses the codes, production channels, and communication circuits of the art world to build symbolic but useful pieces of infrastructure in Syria. These projects, which so far include two further iterations, Current Power in Syria and Revolution Is a Mirror, propose that infrastructure can be both architecture and sculpture. Each “monument” is an object in a landscape built collaboratively on-site. (Current Power in Syria is a windmill providing electricity to a building in the Eastern Ghouta, a devastated suburb of Damascus, where the residents’ lives depend on it.)

The story of the construction of each object is told in a series of small books, which are made available for free whenever “Monuments of the Everyday” is featured in exhibitions. If the infrastructure actually dazzles on the ground—fresh water! Independently provided power!—the books do something different. They traffic in none of the morbid curiosity or sticky sensationalism that often characterizes documents such as the Amnesty report on Saydnaya. Instead of reproducing the brutality of the conflict, as a lot of the work that cooke writes about unfortunately does, Malas’s books make much broader connections and link the

current crisis back to the lessons of a long, and sometimes whimsical, history. Malas is an analytical thinker and a gifted writer. He tells the story of the wells through episodes about mechanical flight over Syria in the past hundred years, from an Ottoman monoplane to an Arab cosmonaut and the dismal phenomenon of the barrel bomb. Malas uses anecdotal narratives to add poetic and historical layers to the infrastructure on the ground, contextualizing the works with interesting—at times even uplifting—material drawn from sources in literature, politics, and film. For example, he illustrates how communal utilities such as water and power have shaped ideas about nationalism and citizenship. In this sense, the people who built the windmill in the Ghouta are testing out what a sounder, healthier Syrian state could be. Malas describes this windmill, in Current Power in Syria, as “a humble monument to our resistance and an expression of our hope.” In returning to the notion of electricity (and electrifying civil disobedience) as a source of enchantment, he also argues that what was known in medieval times as magic—the marvelous, mysterious, artificial, and immaterial—still operates today and is the same thing that animates what we call art.

Another project, addressing a very different aspect of the war, turns the story of what’s happening in Syria around. Instead of cataloguing horrors, Europa: An Illustrated Introduction to Europe for Migrants and Refugees offers to those who have left the country the embrace of a warm, helpful, informative, and, above all, generous welcome. The brainchild of the artist and photographer Thomas Dworzak, the publication has all the elements of a gorgeous photo book: recent and historical images by the likes of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Elliott Erwitt, Martin Parr, and Jérôme Sessini, among others. But this book wasn’t made for photography lovers, who likely don’t know about it anyway. It was made explicitly for refugees and migrants. Europa is a clear-sighted, beautifully straightforward, and deceptively simple introduction to the idea, history, and practicalities of Europe for people seeking asylum.

Crammed with useful information, the book was constructed in layers by a team of impressive writers, editors, and other advocates.Linking the wars of today back to the wreckage of Europe after World War II, it emphasizes similarities rather than abject differences. It also diversifies the idea of “giving voice” to those who have suffered. There are certainly stories of young men barely making it across the Mediterranean in flimsy boats, watching fellow passengers drown and die. But there are also stories such as those of Leila, a thirty-six-year-old social worker born in Paris to a family of Algerian and French Guianan heritage. She grew up as a Buddhist and later became a devout Muslim. She wears a veil but also shaves her head, because “you wanna see what’s under that hijab? Sorry, boo, no long black hair, soft and shiny like in your ‘1,001 Nights’ fantasy. I’m not Jasmine from ‘Aladdin.'” More? She has three children, a supportive ex-husband, and identifies as queer. Atypical and unexpected, Leila’s story epitomizes the complexities of identity and experience that complicate the binaries of insider and outsider that are so often exploited to make people fearful of others. It takes an artist’s touch to make those details work in a book addressing a grave crisis in a hopeful and emphatically nonviolent way.

Six months before Amnesty released its report on mass hangings in Saydnaya, the organization collaborated with the sound artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Forensic Architecture, a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London, on a project about the prison. Abu Hamdan interviewed former detainees, playing them a series of sounds and “echo profiles,” and he spoke at length with them about what they remembered hearing in the prison. From that, and the notion of the earwitness, he and the rest of his team were able to construct a digital model of Saydnaya (the Syrians grant no access to it, and very little is known about the prison despite its notoriety). Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison is an interactive Web platform that literally maps and demystifies the prison. On one hand, it creates a bold, factual narrative about the prison as a knowable object, rather than a haunting but elusive nightmare. On the other, it moves through the stories of survivors who have had their subjectivity restored, who are no longer objectified by their torture.

Last August, when the website went live, a number of defectors who had worked in the prison came forward and gave further testimony. That, in turn, led Amnesty to discover the method and location of the executions—mass hangings in a basement room. “Artists have a certain intensity in looking at the world,” Abu Hamdan said recently when asked about the Saydnaya project. They also do things differently. In his collaboration with Amnesty, he insisted on interviewing the former detainees as experts, as specialists in what they had experienced rather than as victims stripped of everything but the barest elements of their lives. “My politics is not to construct them as victims,” he said, and not to perpetuate the violence that was done to them. In Saydnaya: Inside a Syrian Torture Prison, they are not people to be pitied but voices to be listened to. Amnesty has since started using some of Abu Hamdan’s questions in further interviews, and one imagines the organization itself might change over time by taking onboard the way artists work. The tricky part of a project like Saydnaya, or Europa, or “Monuments of the Everyday,” or the work covered in cooke’s Dancing in Damascus, is to fight the images of the regime’s violence and find different stories to tell, narratives other than the ones we already know, where everyone dies, all is lost or futile, and nothing can be done. On the conflict in Syria, Abu Hamdan added: “It’s a place that demands thinking.” This is certainly true and should energize artists and writers who are driven by tough challenges and daring ideas. They might prove cooke’s theory correct, and create a new country through critical thinking and engagement. In the meantime, one hopes for some more practical magic from the likes of Malas, Dworzak, and Abu Hamdan, for that might really make a difference, for Syria and the world.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a writer based in Beirut and New York.