Among those who consider themselves serious readers, it’s seen as infra dig to treat literature as self-help. Fiction is not there to teach us how to live or to help us imagine different ways out of our mundane personal difficulties. Nabokov is stern on this in his Lectures on Literature: “Only children can be excused for identifying themselves with the characters in a book.” Any of us who nonetheless persist in, say, taking a novel as a model for our love lives, might hesitate to start with the nineteenth-century Russian canon, unless we aspire to be connoisseurs of suffering. Not so the mother of Selin, narrator-protagonist of Elif Batuman’s playfully titled first novel, The Idiot. Selin’s mother informs her that Anna Karenina “was about how there were two kinds of men.” There were

men who liked women (Vronsky, Oblonsky) and men who didn’t really like women (Levin). Vronsky made Anna feel good about herself, at first, because he loved women so much, but he didn’t love her in particular enough, so she had to kill herself. Levin, by contrast, was awkward, boring, and kind of a pain, seemingly more interested in agriculture than in Kitty, but in fact he was a more reliable partner because in the bottom of his heart he didn’t really like women.

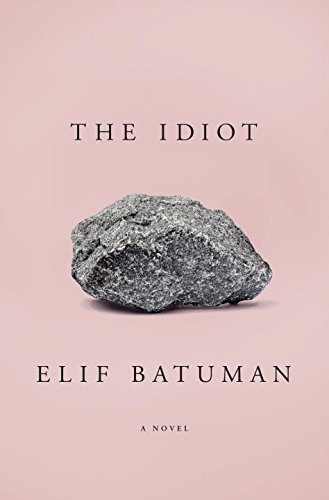

Like a few other minor details in The Idiot (for instance, a “leg contest” in which the narrator must grade the lower halves of a group of pubescent boys in a remote Eastern European village), this mother and her practical take on Tolstoy also appear in Batuman’s 2010 essay collection, The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them. “Is Tolstoy saying that it’s better for women to be with men like Levin?” Batuman’s nonfictional mother asks her. “Kitty made the right choice, and Anna made the wrong choice, right?” It’s not an unimportant question, and neither is the one that lurks beneath it: What does a novel “really mean” (a favorite phrase for Selin’s mother), and what is it for?

Selin has a lot of time to contemplate this sort of problem because she is in college: The novel begins with her arrival as an undergraduate at Harvard. Her early samplings of literature classes feel frustrating precisely because of the serious-reader hurdle: “You wanted to know why Anna had to die, and instead they told you that nineteenth-century Russian landowners felt conflicted about whether they were really a part of Europe. The implication was that it was somehow naive to want to talk about anything interesting, or to think that you would ever know anything important.” In other words, everyone understands the silent decree that if you are going to extract any useful information from a novel, it should be about something less frivolous than love (Selin’s mother’s analysis, for example, might not help us account for the significance of the “tremendous amount of wheat” immortalized in Woody Allen’s Love and Death).

Now a staff writer for the New Yorker, Batuman, like Selin, grew up in a Turkish family in New Jersey and attended Harvard. She’d intended to publish fiction earlier in her career, but had reservations about some of the work she saw emerging from craft-fetishizing MFA programs: The stories seemed to inhabit an eerily ahistorical world in which “middle-class women keep struggling with kleptomania, deviant siblings keep going in and out of institutions, people continue to be upset by power outages and natural disasters, and rueful writerly types go on hesitating about things,” all in prose lovingly stripped down to “a nearly unreadable core of brisk verbs and vivid nouns—like entries in a contest to identify as many concrete entities as possible, in the fewest possible words.” Instead, Batuman spent several years at Stanford doing a Ph.D. in comp lit—years described in The Possessed in a series of essays that establish a gently comic “Elif” character to whom unexpected things tend to happen. (When a man at an academic conference questions her credentials for understanding Isaac Babel’s “specifically Jewish alienation,” she responds: “As a six-foot-tall first-generation Turkish woman growing up in New Jersey, I cannot possibly know as much about alienation as you, a short American Jew.”) The reason I remembered that both mother and leg contest were drawn from life is not because I suspected Batuman couldn’t have made them up: It’s because the worlds she constructs in both fiction and nonfiction are so recognizably hers that once you encounter a Batuman mother or leg contest (or canoe, or ice palace), you don’t forget it. (“Constructed Worlds,” incidentally, is also the name of an enjoyably pretentious studio-art class Selin takes.)

The Idiot is in one sense a coming-of-age story of a fairly traditional kind, and yet Selin’s developing consciousness is a stranger and more fun place to be than most: She sets about not knowing what she wants with rare energy and purpose, and meets the pains and indignities of youth with an unfailing, almost cheerful curiosity. For instance, plagued by a cold while interviewing with a professor to join his class, she scans her peripheral vision for a tissue box and, finding only books, dwells on “the structural equivalence between a tissue box and a book: both consisted of slips of white paper in a cardboard case; yet—and this was ironic—there was very little functional equivalence, especially if the book wasn’t yours.”

Although the sheer entertainment her prose offers doesn’t require that we constantly think about how it works, Batuman is an unapologetically literary creature. She knows that the way you tell a story is the story. After Selin starts taking a Russian-language class, chapters of a narrative called “Nina in Siberia” begin to intersperse the text of The Idiot. In it, Nina’s boyfriend, Ivan, disappears and she must go to look for him, but everything that happens is described using only the grammar the novice Russianists have learned so far. This entails some contortions: Since the class can’t yet handle the dative case or verbs of motion, no one in Chapter 1 can tell Nina straight out that Ivan has gone away, or hand her a letter from him (instead, someone tells her that on the table is a letter, in which Ivan mentions that by the time she reads it he will be in Siberia). While reading “Nina in Siberia,” Selin notes, despite the weird, grammatically challenged tone, “you felt totally inside its world, a world where . . . what Slavic 101 couldn’t name didn’t exist. There was no ‘went’ or ‘sent,’ no intention or causality—just unexplained appearances and disappearances.” As the grammar gets more complex and the truth about Ivan emerges, students must act out the parts in key scenes, sometimes accidentally changing the course of the story with their small mistakes. What could be an irritating device is instead both comical and oddly suspenseful.

It also offers an oblique insight into what Selin is feeling: The story’s progress somewhat parallels that of Selin’s involvement with one of her classmates, a real-life Ivan, a brooding and “almost unreasonably tall” Hungarian math major. He remains a peripheral character for several chapters, but there are signs (even if you don’t count the gloomy trajectory of “Nina in Siberia”) that he will make our heroine suffer. At one point, she notices that he’s reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being (in Hungarian, but she recognizes the bowler-hat cover). They eventually begin a kind of epistolary romance, by which I mean that each sends the other intense e-mails only tangentially related to their everyday lives or to whatever message they are putatively answering (one of Ivan’s offerings is a detailed account of the fate of several statues of Lenin in Budapest that also mentions Mayakovsky’s suicide). Batuman has a very precise sense of the insular, playful seductions of e-mail, a medium that facilitates both instant intimacy and isolation—it’s an ideal form for an obsessive and unequal love affair, solipsistic and outward-reaching at once, and most importantly rife with opportunities for a sudden and irrevocable lapse. We know Selin is lost when she observes of Ivan that “everything he said came from so thoroughly outside myself. I wouldn’t have been able to invent or guess any of it.” Such a brilliant, handsome, grumpy young man—and such good material! Everything about Selin makes it clear that she is doomed to become a writer. Soon she and the reader will be spending a hundred or so pages in rural Hungary for no real reason other than Ivan’s charms and the vague sense that one should always do the trickier, more adventurous thing when afforded the opportunity. That’s a policy Selin seems to share with her author, who has elsewhere claimed to follow the Jamesian maxim from The Portrait of a Lady that “one should never regret a generous error.”

Batuman wrote in The Possessed that, after years of people questioning her decision to study the Russian novel instead of taking the easier path with Turkish literature (since she already spoke the language), she eventually grasped that “love is a rare and valuable thing, and you don’t get to choose its object.” Selin’s experiences, too, suggest that reading is inherently erotic. They also reaffirm the Proustian insight that love itself often involves an interpretive excess: Of the unknown young man who has written his name in the book she’s reading and filled it with seemingly nonsensical underlinings, Selin jokes, “Thank God I wasn’t in love with Brian Kennedy, and didn’t feel any mania to decipher his thoughts.”

When a smug college counselor diagnoses her as taking refuge in the e-mail affair with Ivan precisely because it’s not real, Selin never goes to see the counselor again. In a banal sense, he is right that Ivan will prove a disappointment, but what he fails to grasp is that for Selin, written language is at least as real as anything else, so love that takes place through it has a special value. Selin’s friend and foil Svetlana—a sophisticated Serb who believes it’s possible to make anyone fall in love with you and thus vacations with her crush and his girlfriend—has a far clearer understanding of the relationship between Selin and Ivan. Selin, she points out, is vulnerable to Ivan’s mind games because she believes that “language is an end in itself . . . a self-sufficient system.” Ivan, after all, is a mathematician, and as Svetlana puts it, “Math is a language that started out so abstract, more abstract than words, and then suddenly it turned out to be the most real, the most physical thing there was. With math they built the atomic bomb. Suddenly this abstract language is leaving third-degree burns on your skin.” Ivan understands the physical power of language and how to manipulate it, and Selin, by nature “so ready to jump into a reality the two of you made up, just through language,” allows him to take the whole game further than most other people could. For her part, Selin is mystified as to the appeal of Svetlana’s love object, unable to see his existence “as any kind of a miracle.” But then “wasn’t that itself the miracle—that love really was an obscure and unfathomable connection between individuals, and not an economic contest where everyone was matched up according to how quantifiably lovable they were?”

Like reading, love works in roughly the same way every time, but the details of any given case are irreducibly particular, and it’s in the details that everything happens. To say that you shouldn’t read Anna Karenina for love is a bit like saying that it’s better to write a novel based on “real life” than on other books—it assumes that those two things can be meaningfully separated. The Idiot is a portrait of a mind examining itself and everything else, an argument for the occasional generous error, and an incidental confirmation—not in its plot but in its execution, which is the only way a novel can confirm anything—of the theory that it’s possible to make anyone fall in love with you. Even Nabokov conceded something like this, in his no-concessions manner. The great writer, he said in the Lectures, is an enchanter. Batuman says come with me and we go, and we don’t regret it.

Lidija Haas is Bookforum’s senior editor.