When you sit down to read a review, as you are doing right now (unless you are standing—in which case, please sit down and take a minute), you rarely have a sense of where the critic is writing from: what time of day it is, what she has eaten, what else she has just read or seen, what’s on her mind. But all of this factors into the work, just as wherever you are as a reader, and how you are feeling, will, too. The pleasure of a critical essay can often be the escape it grants from diachronic time; the living room couch fades away into a painting’s scumbled imagery or a book’s knotty metaphor. Lynne Tillman’s writing shows us the pleasure of another, more pedestrian edge of the written experience, in which we are still with the writer, watching TV in her apartment, or reading in bed after a trip to the National Gallery of Art. Enter Madame Realism.

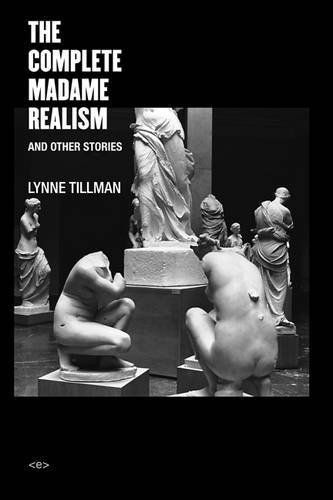

Madame Realism is a work of art who discusses works of art. She’s a witty, deadpan critic, invented by Tillman as a foil to the male heroics of Surrealism (Sir Realism). (And, I assume because of this, as a retort to a gender-biased understanding of the unconscious and its chains of associated thought.) She first appeared in an eponymous book published in 1984 and illustrated by Kiki Smith, then in occasional columns in Art in America through the 1980s and ’90s (eliciting some great letters to the editor questioning her fitness for the job), and she has continued to pop up in exhibition catalogues and Tillman’s writing over the years, including the short-story collections This Is Not It (2002) and Someday This Will Be Funny (2011). Here, for the first time, we have the “complete” Madame Realism stories, all fifteen of them—though it seems against Madame Realism’s spirit to posit an end—along with the “complete” Paige Turner stories (another Tillman persona, this one tangled up in questions of love), and six other fiction-essays, bookended by M. G. Lord’s and Andrew Durbin’s effusive essays.

We find Madame Realism wandering through exhibitions and bars, notebook or tape recorder in hand; she goes to Ellis Island and Coney Island and a Jeff Koons conference in Athens. Madame Realism levels genres and categories as she crosses them: fiction and nonfiction, the short story and the critical review. But Tillman goes further, also stretching the bounds of the story’s setting, its setup, and even its argument for existing. In her perambulations, she takes on every kind of expository tool by which we come to understand a work of art, whether she’s deconstructing an audio tour, dissecting wall labels, or physically inhabiting an exhibition catalogue. “It’s a thin line between art and popular culture,” she says, “and one can jaywalk easily if all objects are not thought of as inherently valuable.” She never passes judgment, she just passes through: “Madame Realism couldn’t decide what was trivial, insincere, fake, inauthentic, frivolous, superficial, and gaudy; she herself was all of these. . . . Reality was a decision she didn’t make alone.” (I kept wondering what Madame Realism would make of a Trump White House press conference—another reason it’s a shame she’s retired.)

At the center of this book, as with so much autobiographical fiction (from Paul Auster to Tillman’s Semiotext(e) compatriot Chris Kraus to Ben Lerner), is the life of the artist-writer. Tillman’s fashioning of that life is unique and unpretentious, even when she slips into the persona of a middle-aged man (in “Drawing from a Translation Artist”). In one story, we find Madame Realism musing, “As I walk to the subway I’m struck again by other people’s epiphanies. I’ve read about them over the years in biographies of artists and writers. These people know and see clearly, and their lives are set out in front of them in one brilliant flash of insight. Will that ever happen to me, I ask myself, searching for a subway token.” Many Madame Realism essays conclude long after her return home from the show she is ostensibly reviewing, with her staring out a window of her apartment at night, collapsing into bed, snuggling with her cats, turning off the TV and the light. There’s a refusal to shape a true, victorious “ending”; the writing slouches off into a vague digression before the passive denouement of sleep. There is no summation, no struggle or anxiety or heroics. Madame Realism dissembles, shrugging off her potential authority and any emotional attachment to her observations.

When the fourth wall is broken, as it often is, it is usually to prick a fantasy before it balloons into anything too self-serious; and to stop us short as readers, too, preventing us from romanticizing a writer’s room and its hissing radiator. So, we have moments like this: “Madame Realism walked over to her window and looked up at the dark sky, the kind that in the country would be full of stars. But here just a few were visible, positioned economically, almost like asterisks or reminders.” And then, lest we get too lost in this arresting, lofty image of a New York in which even the cityscape is efficient, bulleted: “Madame Realism left the next day.” Before we can really place her, she has moved on to the next story.

This question of presence seems crucial to Tillman’s project. Her position in a text is tricky—she operates both inside and outside of it, which allows her to thwart distanced critical authority and also perform the aesthetic slippages she admires in others’ work. Take, for instance, her essay on the artist Cindy Sherman near the end of the book, in which she describes not just the photographer’s generation and artistic milieu but also her own. When analyzing Sherman’s work, Tillman seems to be saying something about her writing simultaneously:

Playing all the roles—camera, subject, object—she is also initially a viewer, the picture’s very first viewer. She performs inside and outside of the frame, as seen and seer, even seeker. Her several positions conceive a “subjective” and “objective” framing. When Sherman stands outside of the frame, she can experience it as a viewer might, and can physically register as a viewer, to imbricate, imaginatively, a viewer inside the frame. She creates a dynamic object relationship among the elements. If Sherman were a novelist, I’d propose: she has incorporated the reader into every text, by allowing for a subjective space for the reader/viewer.

The “author” Sherman as the picture’s first viewer is parallel with Tillman as her own writing’s first reader. This collusion of looking and reading, seeing and writing, creating and consuming, is the book’s subplot. We read because we are looking for something, and the way we look at the world is a way of reading, too. Much like Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, these fiction-essays ask what our readings are good for, what comfort or pleasure or knowledge they bring us, how they shape our lives.

The first sentence of the first Madame Realism story has her reading (and then quoting) another writer, Paul Éluard—placing her in a subtly complex subject position in which she is already also a reader like us. At one point, Madame Realism realizes that she could become what repulsed her, a fate she likens to being “a quotation from a work or book I hated.” Quoting someone is a form of identification, but it is also a kind of distancing, a way of placing another’s ideas in front of your own. This is the constant dance here, an echo of modernism’s reworking of the material scraps of history and originality—think of Walter Benjamin’s unfinished Arcades Project, with its ceaseless citations and catalogued inventories of stuff. “Where a story takes off is invariably in media res and enmeshed in other stories,” Tillman writes. Her work exposes that active middle state—and those things—expecting that the reader can and will make the necessary connections to form a narrative.

What do we get from this inside/outside exposure of the author? At its best, it makes the story’s hull clear, like a kayak outfitted for a bioluminescent bay; we can look through it and see the water rushing past with silver flashes of thoughts in its stream. The stream is the sound of the characters’ voices wondering out loud, seemingly without filter, a refreshing immediacy of experience too often expunged from a standard review. At its weakest, this technique feels like a shortcut, a way to tell the reader I know what you’re thinking or Don’t interpret me. Madame Realism is constantly distracted from finishing one thought by another thought, and while these associations can be charming, and often funny, they can also be frustrating dead ends. (Some of Tillman’s best pieces take place in carnival settings where the fractured, dizzying lack of focus is refracted in the writing style.) Sometimes the limits of a critical essay’s factual hypothesis, like the structural confines of a sonnet, help to emphasize the beauty of the limitless art therein. Sometimes, as a reader, you want to stay at the exhibition rather than returning home with the reviewer.

For me, the book’s revelation is “Still Moving,” which originally appeared in a 2016 catalogue of Justine Kurland’s photographs. Its eight terse scenes have a Lydia Davis–like economy in their vivid perspectives of childhood and familial relationships. The blunt imagery is never interrupted by a narrator; it hangs in the air after you have finished reading. “She and her mother camped in fields where trees without names sheltered them from the sun, and a sky of dazzling stars lit up their nights. She did her homework, and then ran around until she fell down, breathing like a racehorse.” In the final scene of the story, a boy accompanies his mother to the beauty parlor, and on the way home “he’d tell his mother her hair looked beautiful. ‘Do you really like it?’ she’d ask Bobby. ‘Oh yes, Mama, I do.’ ‘Any of that shit,’ his father yelled at his mother, ‘any of that shit comes off on him, it’s on you.'” I will miss Madame Realism. But perhaps Tillman’s most recent excursions in exhibition-catalogue fiction offer us the most evocative realism of all.

Prudence Peiffer is an art historian and a senior editor of Artforum.