THAT IT’S COME TO THIS—that I actually find myself, in private thought, trying to explain to nobody in particular (but also to the president of the United States) why we really would be better off letting most of our immigrants stay here, whether they are credentialed or not—it’s like having a song stuck in my head, only instead of a song there’s just my own inner voice delivering a kind of wheedling lecture on the Golden Rule. My imaginary interlocutor couldn’t care less: His eyes glaze over, and he’s puttered off to command a new round of ICE raids and/or unleash more tweets before I have a chance to mention the gifts that foreign-born people and their children have bestowed upon our American vernacular—a language continually reinvigorated by those who spoke other languages first and have come at this one from a slant.

Although my imaginary nonlistener has never read a work of serious fiction and is not about to start now, I could offer, as Exhibit A, the stories of Grace Paley, who grew up around family and neighbors speaking Russian and Yiddish and an inflected Bronx English. With that as her inheritance, Paley, who died in 2007, transformed the ordinary English sentence. It’s not that her material is secondary—her style is too bound up in her subjects to overtake them—but even so, a reader of her fiction might be propelled forward simply by gratitude for the generous linguistic intelligence that resides in it. “There is a certain place where dumbwaiters boom, doors slam, dishes crash; every window is a mother’s mouth bidding the street shut up, go skate somewhere else, come home. My voice is the loudest,” announces the narrator of her early story “The Loudest Voice,” before continuing: “In that place the whole street groans: Be quiet! Be quiet! but steals from the happy chorus of my inside self not a tittle or a jot.”

The nice thing about A Grace Paley Reader, aside from the reminder that now would be a good time to read Grace Paley (and it so happens that now is a really good time to reread, or read for the first time, her work, which is full of energetic struggle against tyrannies small and large), is that by bringing together a selection of her stories, nonfiction pieces, and poems, it illuminates the connections among them, along with the intertwinings of work and life. A casual fact from one of the essays—that her mother had perfect pitch, an ability not passed on to Grace—sits in proximity to the evidence of the daughter’s extraordinary ear for language, as though one auditory talent had mutated into another.

Growing up, Paley was surrounded by adults and near adults—she lived with her parents, her grandmother, her aunt, and two siblings fourteen and sixteen years older—and in that crowded home, I imagine, she must’ve been eager to catch up, to understand what everyone else was talking about. Moreover, as she relates in another essay, she felt herself “an outsider in our particular neighborhood” because her family spoke mostly Russian while others spoke Yiddish, so that “it seemed to me that an entire world was whispering in the other room.”

Later on, in her stories, she would create heightened versions of her New York neighborhoods, and even the most showy of her sentences are grounded in those apartments and parks. Her voice never becomes so pleased with the sound of itself that it leaves off with what it considers the meat of the matter—and if maybe it does sound pleased with itself from time to time, the reader can share in that pleasure. It is remarkable that a voice so acrobatic and sly and playful still rings so true.

GRACE GOODSIDE (whose parents had changed their name from “Gutseit” when they arrived in America) enrolled at Hunter College after high school, but she rarely made it to her classes. In an admiring 1993 biography of Paley, Judith Arcana reports that young Grace had every intention of going to class, but “on the way into the building, going up the stairs, she would hear something—maybe a scrap of conversation, a story being told—that would catch her mind and take her away, right back down the stairs and out of the building.” Reading Paley’s stories, especially the later ones, is something like trying to follow her to class: She starts off in one direction, but then something else, a conversation or other voices, interrupts. As it turns out, that overheard story in the stairwell is just as important as what’s being taught in class, just as deserving of our attention, if not more so.

She dropped out, but a couple years later she tried college again, this time taking a class taught by W. H. Auden, to whom she submitted poems in the style of W. H. Auden. He met with her and asked why she wrote that way, whether she or anyone she knew really used words like trousers—write in your own language, he told her.

At nineteen she married Jess Paley, a freelance photographer and filmmaker, and in her late twenties she had two children, twenty months apart. Her kids were still toddlers when she got pregnant again, and, as she would later write in an essay called “The Illegal Days,” “I knew I couldn’t have another child.” She was exhausted, sick a lot, and low on money, and her husband had never been too keen on having kids to begin with. She had an abortion, from a Manhattan doctor who would perform abortions, though they were illegal. (The next year he was arrested and sent to jail.)

Arcana asserts that it was this abortion that allowed Paley to begin writing short stories, though Paley herself was less certain about the timeline. Later in her life she wouldn’t remember whether it was that abortion, or a miscarriage, or an illness that led to a period of some weeks in the 1950s when she was told she needed to take it easy. She sent her kids to day care after school and with the additional hours to herself, Paley, who until then had written poetry but not fiction, typed a draft of her first story, “Goodbye and Good Luck.” Before this, as she would recall in the preface to her Collected Stories, she had been “singing along on the gift of one ear”—the ear raised on literature—but with the stories she found her second ear, one that could “remember the street language and the home language with its Russian and Yiddish accents.”

Her long apprenticeship in poetry influenced her way of writing fiction; the stories seem to feel their way forward by instinct and rhythm rather than hewing to conventional narrative arcs, and their dialogue and narration vibrate with a density of thought. She dispenses with much of the baggage of narrative, the stuff that the critic Hugh Kenner once derided as “the practice of quotidian novelists who dust their pages lightly with detail—’She turned away. Through the leaded panes sunlight poured onto a dusty piano.’—to impart a random feel of reality.” No sunlight pours onto dusty pianos in a Grace Paley story.

Her abiding interest was, as the subtitle of her first collection puts it, “stories of women and men at love.” (For Paley, everything lives and thrives in that subtitle’s at, in opposition.) She placed women first and made singing investigations of their conflicted hearts, as they fend off the insults of everyday middle-class life. By the mid-’60s, she felt she was done writing about the circumstances of her childhood: “I have probably shot my Jewish bolt,” she said, and yet there remained plenty to interrogate, all around her. She found inspiration where you would least expect it, at the playground and PTA meetings. “Luckily for art,” she wrote, “life is difficult, hard to understand, useless, and mysterious.” “In the end,” she writes elsewhere, “probably all I’ll have to show is more mystery.”

THE PLAYGROUND IN A GRACE PALEY story is a lot less boring than the playgrounds I’ve wheeled my kids around to; it is a microcosm of society and at the same time a surreal invention, more spirited and warmer than any actual park. This is, in part, the result of the writer’s ingenuity, but I think it also comes from listening, from the attention Paley must’ve paid to the people at Washington Square Park, where she took her kids, so that she could create a version of the place with the volume turned up. Insofar as that type of attention has mostly eluded me any time I’ve found myself in the long shadow of a playscape, her work seems to come with an implicit message: Wake up! Don’t look at your phone! So much is happening in the world, or could be happening. George Saunders, who wrote the introduction to A Grace Paley Reader, takes this a step further: “Mere straightforward representation is not her game,” he writes. “In fact, she seems to say, the world has no need to be represented: there it is, all around us, all the time. What it needs is to be loved better.“

The playground features centrally in “Faith in a Tree,” a story in which the narrator, Faith Asbury—a character in a number of Paley’s stories—finds herself there, though in fact, like so many parents, she’d rather be someplace else: “Just when I most needed important conversation, a sniff of the man-wide world, that is, at least one brainy companion who could translate my friendly language into his tongue of undying carnal love, I was forced to lounge in our neighborhood park, surrounded by children.” But if this narrator is confined to a terrarium of (mostly) women and children, she will also be its surveyor and chronicler; she sits in a tree and looks down from above.

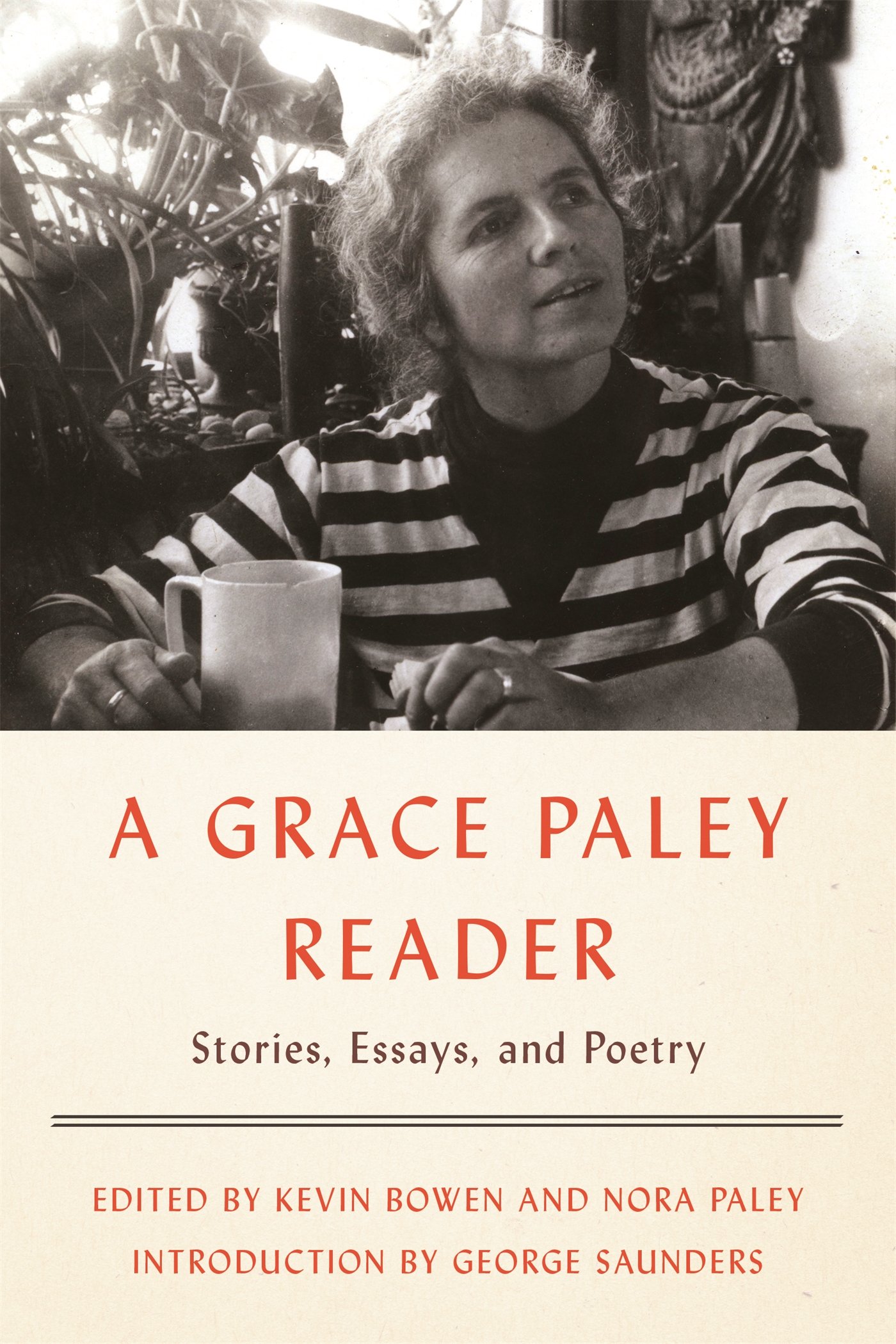

This duality, the tension between lived life with all its restrictions and the freedom of the observer to conjure life in words, runs through Paley’s work. A toddler in one of the stories is described as “falling, already falling, falling out of her brand-new hammock of world-inventing words onto the hard floor of man-made time,” and so are we, so is Paley, continually seeking her aerie of language only to be sent back down to earth and mortality. “Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life,” says the narrator in the story “A Conversation with My Father.” It’s a line that people writing about Paley often quote by itself, though in fact it’s one side of an unwinnable argument: Even as the narrator says it, her father is breathing through an oxygen tank, not long for this world. It’s he who has the last word: “Tragedy! You too. When will you look it in the face?” (But I suspect that Paley really did, in her own way, defy time while continuing to live in it, for in the beautiful photograph on the cover of this book, a middle-aged Paley—a woman with graying hair and lines on her face—manages to look also like an eight-year-old girl lost in thought.)

Men come and go in these stories, essential to life but always slipping away, while the longest, most fond romance is with women (her coworkers in the writing and mother trades, she occasionally called them). In one story her narrator says:

I remember Ann’s eyes and the hat she wore the day we first looked at each other. Our babies had just stepped howling out of the sandbox on their new walking legs. We picked them up. Over their sandy heads we smiled. I think a bond was sealed then, at least as useful as the vow we’d all sworn with husbands to whom we’re no longer married.

And that’s not the only tribute to a friend written in this pitch. Men are sparring partners, but women the steady companions on long walks and intimate talks, the ones with whom you try to figure it all out: How to live? How to cope? Can people change or can’t they?

“Enormous Changes at the Last Minute” was not only the title of Paley’s second book and of one of its stories, but also the mode of many of the stories, which make big swerves toward the end: Politics intrudes on the playground, Sunday-morning domesticity displaces a tale of ball-busting New Jersey businesspeople, a woman of a certain age has a baby by a taxi driver. And Paley’s own life changed enormously in the ’60s and ’70s: After nearly thirty years of marriage she and Jess Paley divorced, and she married writer and landscape architect Robert Nichols. Meanwhile she became a committed political activist.

“EVEN ADMIRING PEERS WORRY that Grace Paley Writes Too Little and Protests Too Much,” declared a 1979 headline in, of all places, People magazine, after Paley was arrested during a peace protest at the White House. There’s a startling photo of her at another protest, this time at the Pentagon: Three tall policemen, caparisoned in their uniforms and helmets and aviator sunglasses, drag away little white-haired Paley (who was five-foot-one) by the arms. She protested—and wrote about—the Vietnam War, US aid to Central American wars, the Gulf War, and nuclear weapons, and she advocated for women’s rights and civil rights.

The “essays” collected here are eclectic, among them articles, remembrances, writing advice, a manifesto, and notes from a panel. (I sometimes wished the editors had provided the context for each.) My favorite describes the six days she spent at the Women’s House of Detention following an arrest at a Vietnam War protest. In jail, she listened, naturally, and the essay captures the voices of the other incarcerated women, who want to know: “Why would I do such a fool thing on purpose? How old were my children? My man any good?”

I happened to receive my review copy of A Grace Paley Reader shortly before the January 21 Women’s Marches, and so she was on my mind that day—and by “on my mind,” I mean really present in my head, an echo of Paley keeping me company as I joined the marchers in Austin, on the lawn of the Texas Capitol. Were she still alive, she would’ve surely been out at one of the protests, holding a PUSSY GRABS BACK sign, or the one that said KEEP YOUR HANDS OFF MY JEWISH UTERUS, or maybe one of the many iterations of I CAN’T BELIEVE I’M STILL PROTESTING THIS SHIT.

The job of the writer, she once said, “is to imagine the real. This is where our leaders are falling down and where we ourselves have to imagine the lives of other people.” To remain open to what you don’t understand, to take a real interest in life, to put yourself on the line. She lived and wrote like that. If today’s newspapers seem not always up to the task of comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable, this book did the trick—that is to say, I found it both comforting and afflicting. And the longer I’ve had it with me, the more I find myself identifying with a title that at first had seemed awfully studious. A Grace Paley reader: I’m glad to be one.

Karen Olsson is the author of the novel All the Houses (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015).