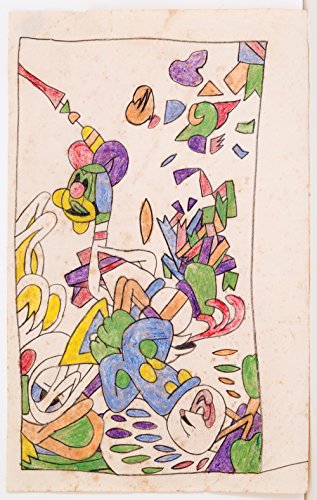

ONE OF MY MOST MEMORABLE apparitions—the sort cast and staged by a certain ill-tasting mushroom—starred Bullwinkle the moose, who demonstrated his ability to grow his already prominent snout to boa-constrictor length. I can still recall that disturbingly phallic vision nearly forty-five years later. My cartoon grotesque comes to mind as I page through this volume devoted to the hallucinatory drawings of Susan Te Kahurangi King. Born in New Zealand in 1951, King became well known in 2008 when her methodically detailed images began to circulate online. The artist, whose earliest work was done shortly after she stopped speaking at the age of seven, presents mutations of cartoon characters from the ’50s, especially Donald Duck. Her rendering of the temperamental fowl evokes Francis Bacon and Edvard Munch as much as it does Disney. Donald is sliced and diced in some drawings; in others, he’s been contorted into painful-looking shapes; elsewhere he’s headless, gape mouthed, and agonized. Woody Woodpecker, Daffy Duck, and Bugs Bunny also turn up, and are similarly modified. All of these metamorphoses hover provocatively between childhood innocence and adult derangement, polymorphous fantasy and mayhem.

The earliest images in the book are crayon drawings done by King at age seven, and it’s hard not to speculate about the relationship between her self-imposed silence (which has lasted to the present day) and the inception of her visual fantasia. Hard, too, not to wonder about the role autism and deafness played in the development of similar private universes conceived by, respectively, Gregory Blackstock and James Castle. The frequent connection critics make between diverse physical and mental states and the deep particularity often associated with outsider artists can be seen as a bit facile; yet the relation feels unavoidable in King’s case. Her fascination with noisy TV cartoon characters—especially Donald Duck, whose raspy speech nearly escapes comprehension—is too suggestive to ignore. Many of her figures are shown gesticulating wildly, their expressive mouths producing what would be the familiar vocalizations. In an untitled drawing (above, right) completed when she was about ten years old, King jumbles Donald’s body—his eyes are disconnected from his face, his legs tinier than his thumb—and he seems to be in midsquawk even as he places an oversize hand inside his bill, as if to stifle the sound. The tension between containment and ungovernable release is intensified by the depiction of his head mushrooming out from under his cap to become some kind of separate entity with its own facial features. A joyous Goofy—rendered rather accurately—seems to celebrate his cartoon pal’s deformation and chaotic enlargement. Hollywood animators may have twisted, snapped, and stretched their creations, but they observed certain rules of visual coherence. In King’s far more subversively elastic domain, these anthropomorphic bodies serve as stand-ins for a disquieting sense of repression and rebellion. The voluble ducks, dogs, birds, and bunnies may have felt like a reproach or a liberation—or both—to King. In any event, her chimerical transformations lend them the force of unvoiced articulation.