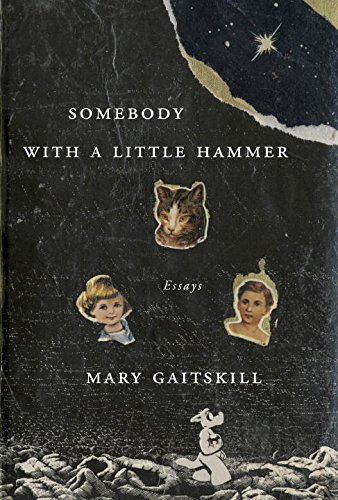

Mary Gaitskill’s nonfiction differs from her fiction not in quality—the essays in Somebody with a Little Hammer are as intense as the stories—but in delivery and voice. Like Chekhov, Mary Gaitskill uses simple, concrete language to bottle human desire. (She would not use that metaphor. In fact, there are few authors less likely to resort to metaphor than Gaitskill.) Here, though, the first person allows Gaitskill to turn the camera on herself in a way that fiction precludes. In her unboxing of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, Gaitskill opens with a joke that both perforates her subject and undoes a stereotype: “By the time the train ride was over, I felt I was reading something truly sick and dark—and in case you don’t know, I’m supposedly sick and dark.” And after you’ve read her on pets, children, fellow writers, and partners, you’ll know that the fierce warmth of a belief in both shared experience and individual consciousness permeates her work. She’s not cold, you weirdos. Was it the jacket photos?

Give or take six years, the essays and book reviews here span the length of Gaitskill’s career so far. You could lose a slice of this book without doing much damage; you don’t need her introduction to Bleak House unless you are reading Bleak House, or the brief piece on Talking Heads and Remain in Light that doesn’t engage either seriously. But Somebody with a Little Hammer makes the case for Gaitskill’s centrality as a writer and burns off dodgy concepts that have stuck to her work. If you have not yet worked through a thought with Gaitskill, Somebody is a primer. It makes entirely clear how seriously she takes the idea of fairness, in life and in fiction, and how averse she is to even the lightest thumb on the scale.

The opening piece is from 1994, a riff on the Book of Revelation called “A Lot of Exploding Heads.” Her conclusion, as a not very religious person who knows the chapter well, sounds like something she might have left tacked above her desk for the next twenty years: “I still don’t know what to make of much of it, but I’m inclined to read it as a writer’s primitive attempt to give form to his moral urgency, to create a structure that could contain and give ballast to the most desperate human confusion.”

Her brief essay on J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, “a book that doesn’t condescend to young children,” is a plug for learning emotional flexibility early and disavowing easy pleasures. When Peter Pan chooses to fly away not with Wendy but with Jane, her daughter, Gaitskill chalks it up to “the remorseless system that we call reality.” If you think she is shilling for brutality, less than a page later she compares Barrie’s version to Disney’s and concludes that, “while the movie has much of the play and irreverent humor of the children’s book, it has none of the gentleness—a quality that for all its sentimentality, popular culture seems no longer to understand.” Gaitskill extends her reach until she is touching both ends of a moral axis and then maintains the position.

While I was writing this I happened to read a review by New York Times critic Dwight Garner, who pointed out that a book’s depictions of “transgressive sex” reminded him of Gaitskill’s work. It is hard to say whether or not something is transgressive, as borders that define transgression are neither natural nor universally recognized. It is more useful to suggest that sex, in fiction, is less likely to be thought of as transgressive in 2017 because of the writing Gaitskill has been doing since the ’80s. Gaitksill’s love of parity means that the sex in her books is usually rendered as the sex that those two people need to have in that moment. “A Romantic Weekend,” one of the stories in her 1988 debut collection, Bad Behavior, involves violent role-playing sex. The story depicts a man and woman trying to convince themselves that this sex is even worth having. What might be dark turns into a comic exchange between two people who are more or less saying “You’re doing it wrong!” to each other, repeatedly. Whether or not this sex was transgressive isn’t really the focus; what drives “A Romantic Weekend” is how the characters adjust their ideas of what is or isn’t sexual, rather than their ideas of what is or isn’t a power dynamic. The whole story is an ad for consent: They know what they’re doing. It’s just hard for two people to get off at the same time on the same thing.

The movie made in 2002 from “Secretary,” another story in Bad Behavior, prompts

a flurry of evenhandedness in “Victims and Losers, A Love Story,” originally published in Zoetrope in 2003. This piece addresses what Gaitskill first characterizes as director Steven Shainberg’s “Pretty Woman version of my story.” Oof. Gaitskill then gently explains the original story, ostensibly to Shainberg, and to all of us. Debby, the secretary in question, is “a sensitive girl acutely attuned to the emotional world.” She becomes sexually involved with her boss, who either abuses her or doesn’t, depending on how you see Debby. Gaitskill clears things up:

Her unformed aggression and cruelty are surpassed only by her unformed tenderness. What a shocking relief when, at work, both impulses are poetically expressed through emotionally violent and intense sex that occurs without touching. Simultaneously, Debby and the lawyer achieve total intimacy and total isolation, and this paradox is the heart of the story’s anguished comedy.

Then Gaitskill’s kindness cuts: “This is an almost impossible story to make a movie of.” Oof 2.0. She allows that Maggie Gyllenhaal, who plays Debby in the film, is a “delightful and unaffected presence,” and that James Spader’s “face subtly reveals sexual feeling that is deep enough to include sadness and vulnerability as well as furtive, guilty meanness, which he does not himself understand.” That Secretary has to exist as a movie on its own merits is not lost on her, and she doesn’t seem very bothered that her short story was the seed. She then delivers a paragraph-length sermon about the role of victimhood in American discourse, the reason one suspects she bothered responding to the movie. Space prevents reproducing the full passage, but it concludes:

To be human is finally to be a loser, for we are all fated to lose our carefully constructed sense of self, our physical strength, our health, our precious dignity, and finally our lives. A refusal to tolerate this reality is a refusal to tolerate life, and art based on the empowering message and positive image is just such a refusal.

Gaitskill especially likes to find the point where humans reveal each other as losers, and then demand that a reader accept the entirety of this relationship. Finality of any kind in Gaitskill’s descriptions is rare. She is more likely to map the points on an emotional exchange and use these as a story’s through line than she is to sustain a plot with cloaks and reveals and other narrative armature. As theorist Lauren Berlant has written of Gaitskill’s work, “All of her books try to make sense of the relation between painful history and the painful optimism of traumatized subjects trying to survive within that history, since they cannot put it behind them.”

Gaitskill’s 1994 Harper’s Magazine essay, “The Trouble with Following the Rules,” addresses both the author’s own experience with rape and the discussion of victimhood then being led by writers like Camille Paglia and Katie Roiphe. She writes that in the original published version of the essay we are reading, she framed an event in a way that she ultimately regrets. After rejecting a friend’s advances, very explicitly, in the moment, she ends up dating the person in question for two years. What she ultimately writes: “But in omitting the aftermath of that ‘responsible’ decision, I was making the messy situation far too clear-cut, actually undermining my own argument by making it about propriety rather than the kind of fluid emotional negotiation that I see as necessary for personal responsibility.” This is how seriously she takes both accuracy and agency. The story of a separate encounter that a younger Gaitskill introduces as date rape is reclassified at the end of the piece. She writes that the young man she encountered in Detroit “was no rapist. He was high on acid and was misunderstanding, just as I was.” She concludes by calling her presentation of the event a “lie.” None of this is in place to buttress her take on the critics of victimhood and self-help culture, like Roiphe. Right after Gaitskill tells the story of a rape that was undoubtedly rape—distinct from the other two more fluid events she describes in the essay—she writes that it “was not so terrible that I couldn’t heal quickly. Again, my response may seem strange, but my point is that pain can be an experience that defies codification.” The variety and depth of Gaitskill’s experience mean that she is arguing with a rhetorical trend of the time using the concrete data of her own experience. And if she’s frustrated with Roiphe’s and Paglia’s lack of empathy for people who identify, for whatever reasons, as victims, the only person she calls a liar is herself. In this case, morality and precision are the same thing.

Two other essays in Somebody take on trauma. The more quickly digested piece is her 2008 election diary, “Worshipping the Overcoat,” written originally for Libération. Her observations on Sarah Palin’s speech at the Republican National Convention are a slap-back echo of the present: “But as I watched her, and the rabid, adoring response to her, I thought something else, which was: This woman is a sadist and she doesn’t know it. And it’s working for her; her people love her for that very reason, and they don’t know it.” There it is, and here we are. Gaitskill being Gaitskill, she refines this question of self-awareness: “Most people don’t know what their driving motive is, and most people have more than one.” Having identified the Palin seeds that fruited as Trump in three sentences, she then suggests the basis for a novel in one.

The book’s most intense piece is “Lost Cat: A Memoir.” Caesar and Natalia are two children Gaitskill and her husband, Peter, meet through the Fresh Air Fund, a program that sends children from urban environments to live with families for a summer in not-urban environments. (Gaitskill lives near an unnamed college—most likely Bard—in upstate New York.) The first exchange with the program puts two unrelated boys, Ezekial and Caesar, into their home. It is grim. Ezekial taunts Caesar ruthlessly, until a choice needs to be made. Someone has to go. For a variety of reasons, Caesar, the weaker and less graceful of the two, loses the Solomonic decision. When a social worker comes to get him, Gaitskill lies, and Caesar calls her on it. The break is as ugly as you fear, and lays open the problems charity creates, no matter the intentions.

That much would be enough, but “Lost Cat” sprawls well. The story unfolds after Ezekial is gone, and Gaitskill maintains close contact with Caesar and his sister, Natalia, because she has genuine love for the kids and their mother seems to be abusive. Through this winds the story of Gattino, the lost cat. Gaitskill goes to almost demented extremes to retrieve this cat. A cat that may well be dead. She pays a psychic one hundred dollars. She spreads a trail of litter-box feces through the snow. She questions dozens of people. Early, before we have the slightest idea whose lives are in play, and before we have even met the kids of the Fresh Air Fund, Gaitskill presents her theory of why Gattino mattered to her:

It is hard to protect a person you love from pain, because people often choose pain; I am a person who often chooses pain. An animal will never choose pain; an animal can receive love far more easily than even a very young human. And so I thought it should be possible to shelter a kitten with love.

As the story unfolds, Gattino keeps not being found, and no matter how many times Gaitskill welcomes Caesar and Natalia into her home, or reaches into theirs, she cannot erase the distance between her and the kids, or heal the original wounds that were not of her making. After years of knowing each other, with Gaitskill regularly sending money to Caesar’s mother, she and Caesar have a phone conversation. Once again, Caesar calls Gaitskill out. He accuses her of thinking she’s better than his own mother, and she can’t respond. His response brings their relationship to the ground, again: “For the first time I feel ashamed of my family.”

In the middle of this asynchronous telling, Gaitskill hears a story on the radio about Blackwater contractors shooting Iraqi civilians during the war. The story overwhelms her and she has to pull over “until I could get control of my emotions.” She writes: “It was the loss of the cat that had made this happen; his very smallness and lack of objective consequence had made the tearing open possible. I don’t know why this should be true. But I am sure it is true.”

The back and forth with Caesar and his sister doesn’t get any easier, nor does finding Gattino. After the emotional luge of “Lost Cat,” you can hear Gaitskill paraphrasing herself: “These are almost impossible facts to make a story of.” There is no reason you can’t skip this and go right to the fiction, except that you’d miss twenty-five years or so of Gaitskill walking you through the facts. Even when you hit some emotional math you’d probably rather round up to save time, Gaitskill won’t let you.

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician from Brooklyn.