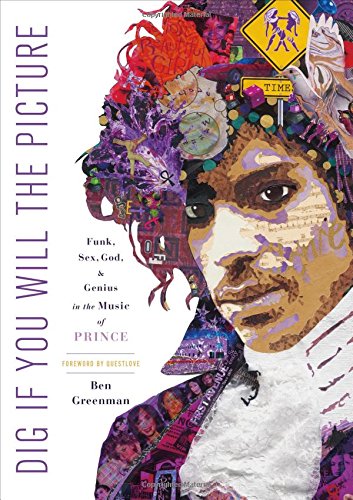

Remember “masturbating with a magazine”? Not the actual act (though that, too), but the opening scene of the late genius Prince Rogers Nelson’s 1984 “Darling Nikki,” in which our hero catches the title character in a hotel lobby, in solo flagrante with the glossy pages of an unnamed publication. As the critic and novelist Ben Greenman reminds us in his new book, Dig If You Will the Picture: Funk, Sex, God and Genius in the Music of Prince (Henry Holt, $28), that line led directly to Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Center’s congressional crusade against “objectionable” music, making it one of Prince’s more politically consequential lyrics. Oddly, Greenman also ruminates on whether Prince meant that Nikki was literally rubbing herself with the periodical or just “holding it” (or having Prince hold it for her) while doing her thing—one of quite a few tangents here that are understandable for a writer knocking out a book fast on the platform heels of an icon’s untimely passing, but that an editor or a friend should have advised against.

But back to that magazine. One wonders, was it in fact porn, a Penthouse smuggled into perhaps the Chateau Marmont in Nikki’s handbag, or something more native to a hotel waiting area, like a People, a Vogue? I imagine it as a music magazine with Prince himself on the cover—perhaps his first time fronting Rolling Stone, the issue of April 28, 1983, with a Richard Avedon shot of His Purpleness and his then-protégée Vanity, each of them with a hand inching toward his waistband. Dig if you will the prospect of Prince discovering his tryst-to-be in the midst of getting off on a picture of Prince. It sets Nikki up neatly in his hall of reflections, Prince’s onanistic oeuvre.

Prince’s work was a gallery of selves and of big-O (in every sense) Others who were both themselves and his alter egos. Greenman limns this well in his discussions of the Artist formerly known as Formerly-Known-As, who was at once a supreme control freak and a sublime collaborator: “Prince may have wanted the idea of his solitary genius to be highly visible, but he also went to great lengths to make it highly divisible.” He shared his gifts (though not always the credit) with his bandmates and all the other artists, mainly women and old Minneapolis compatriots, that he styled and produced and wrote for. More covertly, as we learned after his death, Prince distributed much of the spoils of his success to a long tally of individuals and causes, including many schools as well as Black Lives Matter organizers and the ailing James Brown “funky drummer” Clyde Stubblefield (who died in February of this year).

Symbolically, though, his essence was always dispersed in the music. Not only because he often played most of the instruments—setting drummer self against guitarist self against synthy self against singing self—but also because of the multiple characters, male and female, computerized and organic, sinning and divine, vintage and futuristic, that he voiced from basso to falsetto and in every dialect of American musical language, past or previously uninvented. Greenman has the standard fiction-writer-turned-music-critic’s weakness for debatable literary comparisons, but he’s on to something when he summons up William Blake’s androgynous spiritual paradise of Albion, which could have used Prince’s notorious 1990s male-female glyph as its flag. Sex in Prince’s work obliterated body-mind barriers—as a play-party of avatars, it anticipated the erotic cyberscape to come.

Yet now it has come, and, as much as I hate to say it in the pages of an actual magazine, I can’t help wondering if that “Darling Nikki” lyric will seem illegible in a decade or three. Even today, younger listeners who discover it streaming as track five on Purple Rain might exclaim, “Ew, gross, was her phone out of charge or something?” What ambitious libertine today would bother with print? Of course, they might also say, “Ew, gross, in a hotel lobby?” But the song mitigates against that—Prince always made plausible the dream logic of the scandalously private becoming openly public, and thereby even sacramental.

The exception was with religion itself, where Prince’s private ideas didn’t make the transition quite as well. Paralleling sexual and spiritual ecstasy was a custom that came down to him from soul music, but Prince was drawn to the esoteric, to apocalypse and numerology, in a way that could make his prayers seem freakier than his perversions. (Depending, no doubt, on the listener.) This was especially true after his conversion from Seventh-Day Adventist to Jehovah’s Witness—when, among other things, he started revising his old lyrics to eliminate swear words, doing the devil Tipper Gore’s work for her.

His other most erratic area was around the internet itself, as Greenman ably documents. Prince was an early online adopter, in sync with technology courtesy of his fluency with synthesizers, but he turned violently and litigiously against the Web when it started to seem like the equivalent of a greedy record label, threatening his control of his material. In 1999 (the year to which he’d given a permanent melody), the Artist gave a speech at an awards ceremony for digital-savvy musicians thrown by Yahoo. Greenman happened to be working there then, the one time he met his idol, and quotes him issuing portents: “It’s cool to use the computer, but don’t let the computer use you. You’ve all seen The Matrix. There’s a war going on. The battlefield’s in the mind. The prize is the soul.”

That warning seems prescient in the age of fake news, yet it was almost as if Prince were competing with the medium that was most like him—each of them teeming with near-infinite content, much of it naked and moaning, a stream that never stops running, at all hours of the day. Both Prince and the Internet incense puritans with their sensual profligacy, while their prolific recombinant creativity vexes entertainment-business executives and lawyers (the basic source of Prince’s war with his label bosses at Warner Bros. in the 1990s). His estate is still contending with how to handle the untold hours of unreleased recordings he left behind. Part of the horror of his death on April 21, 2016, at fifty-seven, was the shock that the process could in fact be stopped, even if of late, mere days and weeks before, it had been shown off more effectively onstage than via the dying album form.

Greenman is helpful on where to focus amid the messy late output, for instance on 2014’s Art Official Age. He’s less effective at explaining the volume of that vision: He tries to squeeze it into Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s concept of “flow,” a reference that’s been trotted out by far too many pop-psych and self-help authors. I prefer Prince’s explanation to the New York Times‘s Jon Pareles in 1996, professing his own awe over his music: “If you could go in the studio alone and come out with that, you’d do it every day, wouldn’t you?” Absolutely. No porn site’s enticements could compare.

But any account that stresses Prince’s solitary inventiveness misses the other crucial wellspring, as captured in the slogan of the long-standing free-jazz group the Art Ensemble of Chicago: “Great Black Music, Ancient to the Future.” Prince’s creativity is less cryptic if you imagine him ever buoyed on the tide of African American brilliance that came before, which he knew encyclopedically. (Of course, rock music is black music, too.) As his life and times advanced, his 1980s crossover moves seemed in retrospect like a feint, like calculated camouflage (early on, he even claimed falsely to be biracial). And his catch-me-if-you-can reclusiveness reads now more like a superstar living his black life, mainly in black circles, and sidestepping the blanching effects of the mainstream glare. No question he was an eccentric, but he was an eccentric within a tradition. There was a hall of mirrors, but it had specific reflections in it.

Greenman, white and Jewish, does his best to deal with Prince and race, but he tends to set it too much apart from other subjects. He falls for the misdirection. He tells us about the mythic and scientific sources for Prince’s purpleness, but less about his music’s blackness, aside from obvious factors like syncopation. He names forerunners but is scant on their consequences. He keeps hyping Todd Rundgren as the antecedent to Prince’s one-man-band habits, while downplaying Stevie Wonder; he cites Duke Ellington as the template for how Prince used a band, when it seems obvious that James Brown (who he does mention elsewhere) is the more direct and pertinent model. (Granted, he is better on Prince and Miles Davis, outlining their on-and-off attempts to work together.) Greenman pays tribute to the great Afro-Futurist critic Greg Tate, but he hasn’t fully absorbed the last three words of the lede to Tate’s eulogy for Prince: “Trailblazer. Trickster. Troublemaker. Who was that masked Race Man Supreme?”

This is partly because Greenman’s book, too, is like the internet. Too much so: He credits it as practically his only source, with a casualness that is jarring when he reels off long anecdotes of unidentified provenance. Given all the myths around Prince, better sourcing would help. As a fiction writer, Greenman is insightful about Prince’s lyrical themes and performances of character, but he is comparatively perfunctory on the music itself. He also writes excellently about Prince’s sojourns into film, and his section about Prince’s mainly antagonistic relationship with would-be parodists stands out as an original contribution. But the book has a memoiristic aspect, about Greenman’s own history as a Prince fan, that comes and goes but never gels, perhaps because it never finds an interesting way to deal with his distance from the kinds of identification that black, queer, and other fans felt with Prince. Compare Greenman’s to Tate’s, Hilton Als’s, or Touré’s writings on Prince, for instance, and it feels too much like a hurried browse.

Toronto-based writer Carl Wilson is the music critic for Slate and the author of Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste (Bloomsbury, 2014).