No one seriously concerned with political strategies in the current situation can afford to ignore the “swing to the right.” We may not yet understand its extent and its limits, its specific character, its causes and effects. We have so far . . . failed to find strategies capable of mobilising social forces strong enough in depth to turn its flank. But the tendency is hard to deny.

Those words appear in the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s 1979 essay “The Great Moving Right Show,” but they could have been composed—well, you know. In a piece the year before, Hall had written of “the language of an authentic, regressive, national populism . . . articulated, of course, through the potent metaphors of race.” As Hegel remarks somewhere, Bedtime for Bonzo reappears as The Celebrity Apprentice.

Hall was writing during the rise of Thatcherism, a cornerstone of capital’s repressive political response to the economic decline that began in the early 1970s. This response—really a set of ad hoc responses—now travels under the name “neoliberalism,” and Hall was one of its first diagnosticians, assaying wage suppression, assaults on public services, and racialized police repression. History is not, Hall knew, “a series of repeats”—if a tragedy returns as a farce, it has been transformed—but his work is as relevant as ever, for we are still living out (and dying in) capital’s self-destruct sequence.

Hall’s métier was to tease out the competing histories, the contradictory political, economic, and social forces condensed within a particular historical moment, an excavation of ideology he called “conjunctural analysis.” In a passage Hall discovered in Louis Althusser and returned to often, Lenin writes that the revolutionary moment in Russia had occurred only because, “as a result of an extremely unique historical situation, absolutely dissimilar currents, absolutely heterogeneous class interests, absolutely contrary political and social strivings have merged, and in a strikingly ‘harmonious’ manner.” This condensation of contradictions is the “conjuncture” of a given historical situation, whose currents and interests must be secerned.

As a bundle of contradictions himself—a “familiar stranger,” the title of his memoir has it—Hall was well positioned to parse the “move towards ‘authoritarian populism’—an exceptional form of the capitalist state.” This description will do for today’s form as well (though some will prefer “fascism,” an element Hall does not neglect). So it is well worth attending to the analyses of its earlier British formations collected in Selected Political Writings: The Great Moving Right Show and Other Essays. Thatcherism and its American counterparts are sedimented in our own moment. Not as mere repetitions, but as continuities, effects, harmonies, exfoliations, ramifications, spandrels, cans of worms.

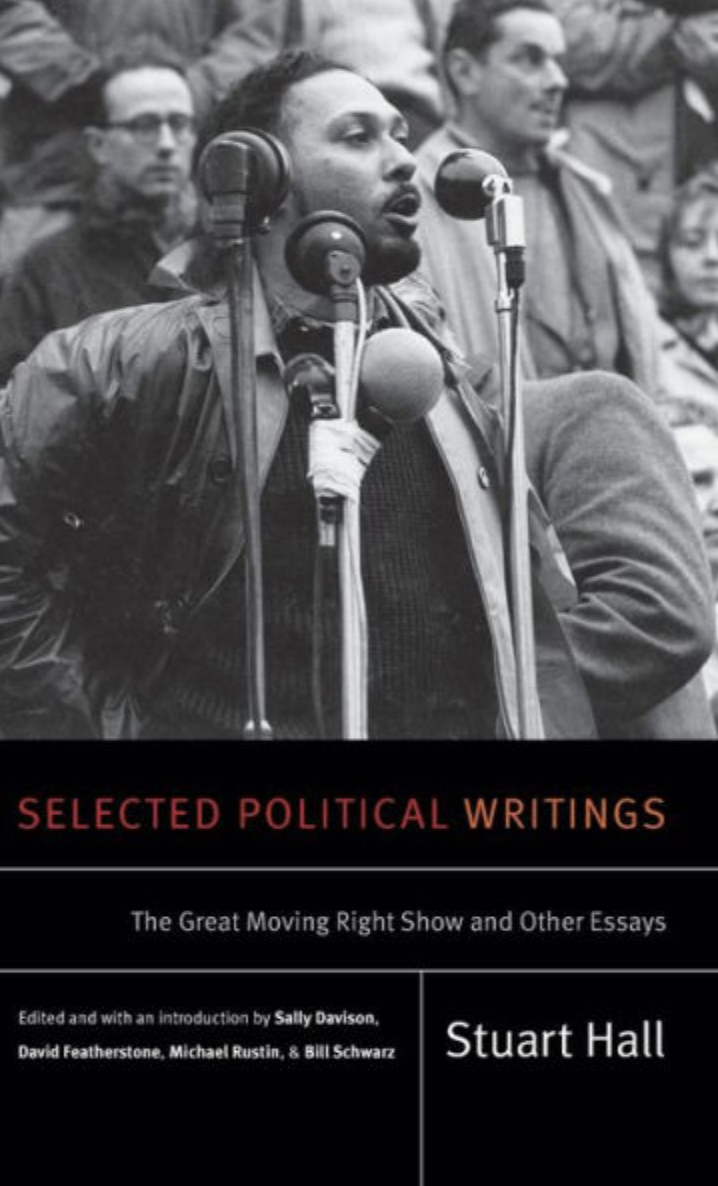

Stuart Hall was born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1932; he arrived as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford in 1951, a black colonial subject in the seat of empire who would become one of the foremost thinkers of the New Left as the director of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University and the founding editor of New Left Review. Duke University Press’s new publications of his selected writings—which include Cultural Studies 1983, a series of illuminating lectures given at the University of Illinois, in addition to Selected Political Writings and Familiar Stranger—present Hall in the full complexity of his thought. Cultural studies doyen, postcolonial theorist, political activist, Marxist: These were for him contradictory but never separate strands. The political writings in particular expand the received picture of Hall in the States, where “cultural studies” is an academic discipline that too often stands at a remove from its radical origins in Marxism and anticolonial struggle.

In the first lecture of Cultural Studies 1983, Hall distances himself from any such reading of cultural studies “as an intellectual project.” It was always “a political project,” he says. If the Centre was interested in the phenomena of mass culture—in football matches and cars and the Clash—it was not because these were inherently interesting (though they might be) but because of what they might tell us about the politics of everyday life. As Hall paraphrases E. P. Thompson, “All the practices in real life are interwoven with one another.”

Hall recounts the formation of cultural studies in the thought of Thompson, Richard Hoggart, and, especially, Raymond Williams, writers who were interested in the forms of traditional working-class culture and their gradual displacement under postwar capitalism, and in the ways ordinary people understood their own experience. This emphasis marked a departure from the orthodox model of Marx’s notoriously ambiguous metaphor of base and superstructure, which was much simplified by Engels. For Lenin, for instance (in some places; in others he is less reductionist), analysis of the economic structure simply accounts for the corresponding ideological superstructures, and that is more or less where things stood for orthodox Marxism in the 1950s.

For Williams in Culture and Society, on the other hand, there is much more to be said about why the idea of culture entered English thought during the convulsions of the Industrial Revolution. Culture is, as Hall summarizes the argument, “all those ways in which historical experiences are understood, experienced, defined, and judged”—as much a site of struggle within as a reflection of material relations.

These conceptions mattered because Hall was “trying to find a language in which to map an emergent ‘new world’ and its cultural transformations, which defied analysis within the conventional terms of the Left while at the same time deeply undermining them.” Hall often spoke of 1956 as a kind of crucible for the Left, with Soviet tanks in Budapest and British and French troops in the Suez Canal Zone. And postwar capital was going boomtown, raising workers’ standards of living even as the third world, about which Hall found the traditional Left had nothing much of value to say, shook off imperialism’s yoke.

It was a new conjuncture, a concept Hall seems to have developed independently before he encountered it in the writings of the Italian Marxist thinker and Communist militant Antonio Gramsci. Hall’s lecture “Domination and Hegemony,” in Cultural Studies 1983 (later integrated into his essay “Gramsci’s Relevance for the Study of Race and Ethnicity”), is a master class in Gramscian conjunctural analysis, which Hall describes as almost too rooted in its own historical moment; Gramsci’s ideas must therefore be “delicately disinterred from their concrete and specific historical embeddedness and transplanted to new soil with considerable care.” Fredric Jameson has recently provided a fine précis of Hall’s own method, transplanted from Italian soil:

Discursive struggle—a phrase that originated in the defeat of the Thatcher years and the interrogations around that victory—discursive struggle posited the process whereby slogans, concepts, stereotypes, and accepted wisdoms did battle among [each other] for preponderance, which is to say, in the quaint language of that day and age, hegemony.

You might have seen, shared on social media, a clip from a 1980 debate between Reagan and Bush, in which each answers a question about “illegal aliens” by calling for compassion and understanding. The implicit proposition that this video demonstrates the moral decline of the Republican Party is worse than absurd, as a glance at either gentleman’s foreign military adventures will reveal. What it demonstrates is an adjustment in discursive struggle and crisis management.

These are the conceptual tools with which Hall drills down into the question of why the victory of Thatcherism took the forms of racism and xenophobia. In “Racism and Reaction,” he deconstructs the Right’s increasingly shrill theme of “law and order,” a dog whistle signaling the restoration of Albion’s proper rulers, whose rightful place had been usurped, through the softheadedness of the nanny state, by the powerless and immiserated, which is to say, primarily by black people and immigrants. The management of capitalist crisis might require that the welfare state be dismantled, but you still have to sell it by teaching your twisted speech to the young believers:

Race is the prism through which the British people are called upon to live through, then to understand, and then to deal with, the growing crisis. The “Enemy” is “within the gates.” “He” is nameless: “he” is protean: “he” is everywhere. He may even, we’re told at the one point, be inside the Foreign Office, cooking the immigration figures. But someone will name him. He is “the Other,” he is the stranger in the midst, he is the cuckoo in the nest, he is the excrement in the letterbox. “He” is—the blacks.

This prefigures Hall’s best-known formulation, from 1978’s collectively authored Policing the Crisis, which eviscerated the racially coded “moral panic” stoked by the British Right about urban crime (a concept well worth revisiting as terrorists massacre the good people of Bowling Green): “Race is the modality in which class is lived.” This sentence, which telescopes an entire conjunctural situation without sacrificing its complexity, aerates the pointless arguments about whether racism or political economy gave us Thatcher or Brexit or Trump: The answer is yes.

Policing the Crisis is represented here by the essay “Birth of the Law and Order Society,” which one wishes were more historically specific than it has proved to be: “The general race-relations crisis now assumed, almost without exception, the particular form of a confrontation between the black community and the police.” It is one of many uncanny reminders throughout these collections that we continue to inhabit the economic crisis that gave rise to neoliberalism and Thatcher, police militarization and obscene income inequality:

In this respect, Gramsci reminds us that a “crisis,” if it is organic, can last for decades. It is not a static phenomenon but rather one marked by constant movement, polemics, contestations, et cetera, which represent the attempt by different sides to overcome or resolve the crises and to do so in terms which favor their own long-term interests.

The most astute analyses of the economic causes of our long crisis are Giovanni Arrighi’s The Long Twentieth Century and Robert Brenner’s 2006 The Economics of Global Turbulence (soon to be reissued in a new edition by Verso Books). If Hall’s salutary opposition to economic determinism sometimes has the unintended effect of downplaying the base, few thinkers in the Marxist tradition have so deftly exposed the gears of ideology. The second essay in Selected Political Writings, 1958’s “A Sense of Classlessness,” anticipates such important critiques of corporate capitalism’s shifting conceptual and linguistic schemata as Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello’s The New Spirit of Capitalism and David Graeber’s The Utopia of Rules.

But Hall, like Gramsci, never doubted that what is ultimately at stake in political and social relations is “the processes by which a mode of production reproduces itself.” Despite various lacunae (the four-page bibliography of Cultural Studies 1983 contains precisely three books by women, two of them novels by George Eliot), his work is all too timely, for the haphazard project of neoliberalism, justified retroactively by nonsensical appeals to the “free market,” is as advanced as the decades-long economic decline it magics away with bubbles and rhetoric (GDP balloons; personal wealth stagnates). The increasingly desperate “pursuit of global capitalist enterprise,” Hall notes in 2011’s “The Neoliberal Revolution,” the final essay of Selected Political Writings, is accompanied, under New Labour no less, by racist state repression at home and support for dictators and torturers abroad. (It is worth looking into, in this regard, the vanquished Democratic Party standard-bearer’s justifications for helping to install, in Honduras, a right-wing military dictatorship that murdered feminist activist Berta Cáceres, who did not hesitate to call her out by name.)

And yet—Romain Rolland’s famous maxim, so closely associated with Gramsci that it is more often attributed to him, is not entirely fatuous. “No victories are permanent or final,” Hall reminds us, predicting countermovements, resistance, and struggle. “History is never closed but maintains an open horizon towards the future.” Though I must note that the last word of this collection is “Alas!”

Michael Robbins is the author of the poetry collections Alien vs. Predator (2012) and The Second Sex (2014; both Penguin). His book Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music will be published by Simon & Schuster this summer.