WHEN PAUL VERHOEVEN CLAIMS he had no choice but to make his latest movie, Elle, in French principally because no US actress would accept the central role, it’s easy (and fun) to believe him. What prudes these Americans are! Naturally, they can’t handle this kind of woman. She berates her male employees at a video-game company for not making their rape simulation violent enough, and after her own rape she calls for sushi instead of the police. She makes herself come while spying through a window as her neighbor unloads Christmas ornaments; she can give the kind of hand job in her office that subtly degrades its boring, asinine recipient; she can transmute almost any amount of fear and rage and humiliation into a sex game. In actual fact, one can’t imagine the role of Michèle being carried off by anyone but Isabelle Huppert, who holds the film’s many potentially contradictory impulses and tones in thrilling tension.

Yet whatever its air of extremity and sophistication, Elle has many of the qualities you find in a certain kind of American blockbuster, not least its too-muchness: Sex is violently unerotic and violence is good cartoon fun; feelings can be nonexistent or operatic but are above all joyously incoherent, which is to say, unpredictable by means of conventional psychology. American audiences, perhaps, don’t always know what it is we want. It makes sense that Verhoeven, who loves to push the blockbuster to its limits and sometimes beyond them, has made indelible hits but also legendary disasters, most famously the intentionally inflated Showgirls (1995), which, as he’s made a point of saying recently, has all along been hailed as a “masterpiece” in France.

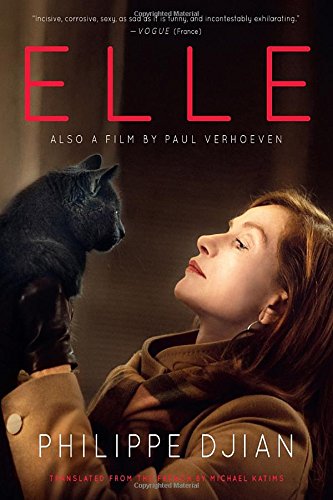

In a sense, the novel from which Elle was adapted, originally titled Oh . . ., loses less in being given the Verhoeven treatment than some books might. It’s by Philippe Djian, who’s best known for the book that was made into the film Betty Blue, and though written in French it cries out on every page to become an American-style movie. The novel opens with a scratch to the face that—as the author has said in an interview—had its germ in Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters, in which a stray cat’s claws prompt New York gentrifiers to suffer a creeping paranoia about literal and figurative infection and invasion. In Djian’s book, Michèle, who, as the story begins, has been raped by a masked intruder in her comfy home, runs a film-production company with a friend. Among her first and most persistent theories about the attack is that the culprit could be a disgruntled screenwriter: “Perhaps I denigrated one person’s work in particular without even realizing it because everything I read blurs into a mass of mediocrity.” (As far as we can tell, her literary tastes aren’t especially esoteric: She’s generally to be found enjoying John Cheever or David Foster Wallace.) The idea that rape could be the punishment for negative feedback on someone’s writing may seem unhinged, but certainly many minds tend that way: Michèle and her female business partner, she notes, routinely receive “wildly obscene insults” in response to their rejections. “There is nothing worse than that feeling of stupidly wasted time when you close a bad script,” she thinks to herself, coolly, less than forty-eight hours after the rape. “Sometimes that wasted time is painful. Sometimes it gets so bad you want to cry. At about 5 p.m. I think of my rapist again.”

The book is almost entirely free of chapter breaks, so that events and moods flow into each other without warning or apology. That seemingly superficial stylistic choice is at the heart of the book’s project, which is to free Michèle from whatever thought or reaction she might be expected or obliged to have and then see what happens. Of course, there’s nothing necessarily challenging about an unpredictable woman, especially if she’s hot enough to keep things entertaining. As the narrator of Betty Blue says of his eponymous muse: “Try to understand everything that goes on in a girl’s head and you’ll never see the end of it. I didn’t want any explanation. All I wanted was to keep kissing her in the dark.” Betty, though erratic and occasionally violent, is a fantasy creature, frequently bare-breasted and prone to saying things about the narrator’s unpublished manuscript like: “You have no idea what it does to me. I’ve never read anything like it.” It’s certainly intriguing, though, that Djian, in making Michèle the narrator, now wants to explore from inside what he once preferred to let us enjoy from the outside. What if we really couldn’t tell what a woman might think next, and not simply because her tits were so appealing that we didn’t need to know?

As Michèle goes about her daily life and work, she stages various revenge scenes, real and imagined, reflexive and premeditated, that play out more or less as sadomasochistic games. She pictures both fighting her attacker and objectifying him, “kicking, punching, biting, grabbing his hair, tying him up naked next to my window.”Aiming the nozzle of her newly acquired pepper spray at a man through his car window, she finds herself “so close to orgasm for one second, as I empty that can toward the shape now convulsing on the seat.” The man on the receiving end, it turns out, isn’t actually her attacker, only her loser ex-husband, hanging around near her house to check if she’s all right—but he does fit the imaginary profile, being a man whose inadequate scripts she has had to reject. “Aren’t we also paying . . . for your lack of imagination, for your refusal to look ahead and your incommensurate love for all things American?” he rages when she tells him his work is no good.

It’s well known that “stranger rape,” which Michèle’s attack initially appears to be, is the kind we are least likely to experience, and the one held up as a model to punish those who suffer the more common kind (presumably an unknown and violent attacker is an ideal qualifier for what Whoopi Goldberg, in excusing Roman Polanski, charmingly called “rape-rape”). But what happens in the book isn’t quite that. The movie is structured as a suspense thriller, one with twists and shocks, but neither it nor the book primarily functions that way—they’re adventures of tone and mood, of who is or isn’t going to hold it together at any given moment. As in Fox’s Desperate Characters, the bourgeois drama here is at least in part about the economy, and Michèle often ponders the crisis of 2007. Djian piles on the dark banker jibes. The sexy neighbor, Patrick, is a “good guy, a bank executive, still surprised at the size of the pile he’s made for himself.” He’s a familiar type, “the pleasant and artificial sort, narcissistic and noncommittal, in a Ralph Lauren polo shirt.” When he pours Michèle some wine, she notes that “one should always be wary of a man who chose to make his career in a bank,” and soon after, another character tells Patrick, “We are the people, so we’re used to getting fucked.” Early on, Michèle even plays down her rape to friends by saying, “I wasn’t really in pain. It wasn’t like it was Patrick Bateman, alright?” Murder, then, is also always in the wings here, but it’s a weirdly playful, unreal kind of murder, the smash-hit movie kind, or the kind that, as in Sade’s Juliette, doesn’t have to be the big deal we think it is—just “a little organized matter disorganized.”

“I’ve known worse with men I freely chose,” Michèle observes in the book’s opening pages. Things get weirder from there, but even just the acknowledgment of the possibility of such a reaction is quite the statement of intent. After all, when a story begins with a rape, it’s hard not to feel that we know what kind of story it will, or should, turn out to be. In On Being Raped,a slim, devastating book published last year, the historian Raymond M. Douglas gives a succinct account of the narrative strictures we usually impose—in life, let alone fiction: “The victim of rape must provide acceptable proof of nonconsent, nonculpability, and nongullibility; assume responsibility for preventing the attacker from committing future crimes . . . pass through the appropriate stages of trauma, minimization, reorganization, and renormalization in an orderly and timely manner; and emerge from the experience a better and stronger person, symbolized by the abandonment of the passive and stigmatizing status of victim in favor of that of survivor.” As well as helping illuminate the plight of male victims, who exist in far greater numbers than many suppose, Douglas’s book is particularly fascinating for the clarity of its observations, a clarity that becomes possible when one separates rape itself from the cloud of heightened feeling and presumption and theory and history that tends to surround any experience primarily associated with women. Douglas also calls it “the nearest thing to a universal law” that in the aftermath of a rape, “everybody else knows better than the victim why it happened and what it really means.”

Novels, of course, have all kinds of opportunities to mean things they don’t say, and to revise their many meanings as they go along. (Michèle’s family background, for instance, which we hear about only in snippets, is almost ludicrously traumatic in a manner that seems by turns crucial to her character and a paradigmatic red herring.) And Verhoeven’s film, naturally, can do things that the book suggests but won’t literally perform. (Verhoeven’s talent for being misread and misunderstood, as he was with both Showgirls and Starship Troopers, here becomes a considerable strength.) There’s the image of Huppert, after sustaining a leg wound, willingly descending stairs into a threatening basement, wielding her cane delicately beside her four-inch heels, resembling Helmut Newton’s shots of Nadja Auermann in an elaborate leg brace. And there’s the video-game design that replaces film production, making Michèle’s work less textual and more visceral, her potential clients automatically more complicit—she is almost literally offering them the chance to experience her attack from the perpetrator’s side. In terms of meaning, symbolism, what is or isn’t real or realistic, it’s far easier for a movie to have it both ways, and for one that pointedly mixes genres (in this, Elle resembles Jordan Peele’s Get Out, another brilliantly uneasy cocktail lobbed at its audience), all the more so. The events of both film and novel could easily fit into several kinds of heavy-handed metaphor, yet the great thing about both is that you never quite need to decide which kind, or whether they really mean it.

Lidija Haas is Bookforum’s senior editor.