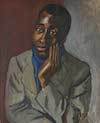

WHEN ALICE NEEL PAINTED a portrait of Harold Cruse in 1950, seventeen years before he published The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, she depicted him thoughtfully grazing his cheek with his fingers, his eyes meeting the painter’s gaze with weathered endurance. Part practicality, part protection, this proximity of hand to face—the standby pose of the untested model—recurs frequently in the paintings collected in Alice Neel, Uptown, the catalogue for a recent survey, curated by Hilton Als, culling paintings from the five decades the artist spent in Spanish Harlem and on the Upper West Side. While Neel’s portraits radiate an undeniable erotic intensity, her subjects don’t always seem to enjoy her attention, yielding instead to the wariness of people accustomed to being watched but not necessarily seen.

Neel was a painter with a voracious visual appetite. Born in 1900 to a white middle-class family in Pennsylvania, the artist settled in the late 1930s in Spanish Harlem, where she spent more than forty years chronicling the community around her through portraits of figures such as civil-rights activist James Farmer, playwright Alice Childress, and Carmen, a Haitian cleaning lady. Other subjects go unnamed entirely, or are reduced to their respective ethnicities: Two Puerto Rican Boys, The Arab, The Spanish Family. Although, as Jeremy Lewison reports in the catalogue’s introduction, Als’s working title for the show was “Colored People,” Als reads Neel’s interest in representing diversity not as a fetishization of other flesh tones but rather as an “ethos of inclusion.” Above all, Neel advocated for what she called “honesty”: depictions stripped of sentimentality or pathos, even when her allegiances lay “with those people who didn’t have the means to speak for themselves.”

In lieu of a single essay, Als intervenes between the paintings with ruminations on individual images. He fixates on the young man in Call Me Joe, 1955 (left), with his eyes set to a soft simmer, a cigarette slipped between the slender fingers of an El Greco–esque hand. Als interprets the boy’s expression as the silent advertisement of an unspeakable longing. He reads a similar loneliness into the crush of a resolute left knuckle against a thin, denimed thigh in Neel’s 1971 portrait of designer Ron Kajiwara. Later, Als marvels at the cocksure swagger of recurring sitter Georgie Arce, “a kid from the neighborhood” with “eyes that give masculinity the stage it requires to wreck and build homes, almost simultaneously.” He lingers on the exquisite watchfulness of the sallow-skinned, blue-frocked girl clutching a blonde baby doll in Julie and the Doll, 1943. As Als observes, subjects like this “remain stalwart in their determination to be, and to hold on to what they have . . . even if the world would rather not know them or anything about them.” With their immediate, unrelenting intimacy, Neel’s portraits don’t give the viewer that option.