A 2015 PHOTOGRAPH of the Obama family’s Passover seder evokes an irrevocably lost world. In it, we see Alma Thomas’s painting Resurrection, 1966, hanging in the White House dining room. This buoyant artwork was the first by an African American woman to be displayed as part of the permanent White House collection. Tastes and regimes change, but Resurrection now enjoys a position of institutional intransigence—if not assured visibility—in this mansion, which was, as the former first lady reminded us, built by slaves.

The image gains added resonance in light of Thomas’s biography. She was born in 1891 in the Deep South, migrated north with her family as a teenager, and lived most of her life in Washington, DC. She taught junior high school and made art in her spare time. In 1960, at the age of sixty-eight, she retired from teaching and dedicated herself to painting, creating electric responses to Expressionistic precedents (Wassily Kandinsky’s synesthetic arrangements chief among them) and to Color Field painting. In 1972, six years before her death, she became the first African American woman to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York). When she received a similar honor that same year at the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington, DC), the then mayor of DC, Walter Washington, proclaimed September 8 “Alma W. Thomas Day,” an accolade that, perhaps unsurprisingly, didn’t prevent future neglect of her work by art institutions.

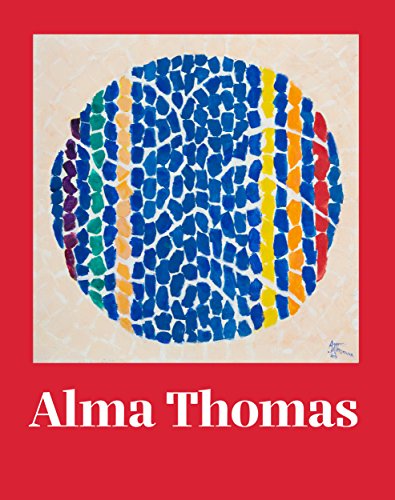

Alma Thomas accompanied a long-overdue 2016 retrospective surveying Thomas’s vital oeuvre, which pulses with hard-won optimism. The volume forgoes chronology in favor of broad thematic sweeps (in sections such as “Move to Abstraction,” “Earth,” “Space,” and “Mosaic”) and is capped by an archive of photographs, exhibition ephemera, interviews, and reviews. The thematic organization adeptly conveys Thomas’s overlapping interests, eschewing the usual monographic narrative of an artistic life moving inexorably toward an apotheosis.

A possible touchstone for Thomas’s work as a whole can be found in March on Washington, 1964, the lone figurative piece in the volume. Once you’ve seen this painting, you start to perceive protesting figures in Thomas’s nonobjective artworks, too: Pigment blocks suggest faces and near-monochromatic patches can seem like poster-board signs. Without text, these “placards” are simply material daubs, signaling incipient potential.