On the morning of June 9, 2012, Avtar Singh called 911 in Selma, California, to say that he had killed his family and was about to turn the gun on himself. When the police reached his house, they sent in a robot equipped with a camera. The feed from the robot showed Singh lying dead in the living room. His wife and two sons were also dead; a third son, the eldest, was still breathing, but he died from his wounds five days later. Each person had been shot in the head.

Singh owned a small transport business; he himself drove a truck. But a decade and a half earlier, he had been an officer in the Rashtriya Rifles unit of the Indian army. Major Avtar Singh was in charge of an army camp in war-torn Kashmir, the mountainous region where the Indian army has attempted to quell, often with disturbing brutality, an armed insurrection and calls for democracy. In April 1997, a police investigation had determined that Singh was guilty of abducting and killing a Kashmiri human-rights lawyer, Jalil Andrabi, whose body had been fished out of the Jhelum River. The corpse had torture marks on it—both eyes had been gouged out—and a bullet wound in the head.

Avtar Singh was never arrested for his alleged crimes in Kashmir, and, despite court orders instructing that his passport be impounded, he was able to leave India for Canada and from there reach the United States. In California, during the year prior to the murder-suicide, Singh’s wife called 911 to report her husband’s domestic violence. The incident drew attention to Singh, and journalists in India were soon back on the case. At the time he killed himself, he was facing extradition proceedings.

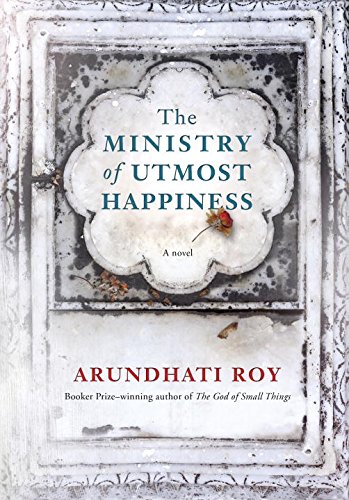

This is one of several news stories that find elaborate fictional form in Arundhati Roy’s new novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. The novel functions as an eyewitness account of what you might have watched, from afar, on the evening news. We see in detail not only these characters’ everyday lives but also their beliefs and the contexts that inform their actions. A rangy and roving novel of multiple, often oppositional voices, Ministry provides us with an intimate picture of a diverse cast of characters: some with homes and privileged lives and others without; some who feel that they belong to a nation and others fighting to create a new one. After more than four hundred pages, we understand why one of Roy’s protagonists, a Kashmiri man named Musa Yeswi, has this to say about the murder-suicide by the former Indian military officer in California:

One day Kashmir will make India self-destruct in the same way. You may have blinded all of us, every one of us, with your pellet guns by then. But you will still have eyes to see what you have done to us. You’re not destroying us. You are constructing us. It’s yourselves that you are destroying.

The novel begins with the story of Anjum, living in a makeshift home in a graveyard in Old Delhi. Anjum was born with both male and female sexual organs—the broad and often ambiguous term used in India for hermaphrodites but also transgender persons is hijra. Anjum’s story is told with a mix of delicacy and humor. As she (Anjum’s chosen pronoun) becomes “Delhi’s most famous Hijra,” many try to project stories onto her, but she remains her own ungovernable self, resistant to the pieties of others: “In interviews Anjum would be encouraged to talk about the abuse and cruelty that her interlocutors assumed she had been subjected to by her conventional Muslim parents, siblings and neighbors before she left home. They were invariably disappointed when she told them how much her mother and father had loved her and how she had been the cruel one.”

The book’s narrator, who frequently stops to offer fierce commentary on all aspects of Indian culture, reveals that Roy’s instinct for satire is as sharp as ever, and her stories about Anjum and her cohort build into a broader portrait of the country over the past few decades. The novel is in many ways an alternative history. In recent years, the right-wing nationalist government in power in Delhi has taken steps to change the content of textbooks: In the official version, Muslims are descendants of marauding invaders, and those on the lower rungs of the Hindu caste-hierarchy are poor animistic savages. Roy offers a different account, one relayed from the margins—not just the viewpoint of Anjum, who is both Muslim and a hijra, but also that of a man who was born into what was formerly considered an untouchable caste. Roy spares no one who is in a position of power. She takes on hollow elites, compromised leaders, murderous politicians, mindless journalists, delusional clerics, even pretend-revolutionaries and famous artists.

Roy is in many ways responding to the nation’s false version of itself, a narrative hijacked by right-wing majoritarianism. There is no drama in such a story: The powerful simply silence the weak. But Roy finds momentum and tension by giving voice to the agents of change. Her book presents a multifarious crowd of protesters—“communists, seditionists, secessionists, revolutionaries, dreamers, idlers, crackheads, crackpots, all manner of freelancers, and wise men”—who gather near Delhi’s Jantar Mantar. (While writing this review, I received news of a group of farmers from the southern state of Tamil Nadu who had congregated at Jantar Mantar with mice between their teeth and skulls around their necks. They were making the point that they would be reduced to a meager existence or even die if the government didn’t provide relief from drought.) For Roy, Jantar Mantar serves as an ideal setting for her portrait of difference and dissent, a space that contains many facets of a wretched opposition. These include “the left-wing, the right-wing, the wingless,” all united in an anticorruption rally. Also at the edge of that circus are the more serious dissenters, such as the activist on a hunger strike on behalf of farmers and tribespeople, the maimed victims of the Bhopal Union Carbide poisonous-gas leak still waiting for justice, and a group of the city’s waste recyclers and sewage workers whose lives have been overtaken by corporations.

Jantar Mantar is also where, about a quarter of the way through the book, a baby is abandoned. She is quickly grabbed by a beguiling woman, who picks up the baby rather than leaving her to the mercy of the police. This woman, who is followed by Anjum’s friends, is S. Tilottama, or Tilo. Tilo is the book’s beating heart, the magical focal point toward which, we soon discover, all desire in the novel flows. With this introduction of a beautiful and rebellious woman flouting the rules of love, The Ministry also begins to read like a sequel to Roy’s previous novel, The God of Small Things, published to sensational acclaim twenty years ago.

Tilo, like Roy, was a student at the Architecture School in Delhi in the 1980s. In college, Tilo was close to three male students, one of whom offers this recollection of her thirty years later: “She gave the impression that she had somehow slipped off her leash. As though she was taking herself for a walk while the rest of us were being walked—like pets.” (Some details of Tilo’s biography recall Roy’s earlier fiction: The reader learns that a scandal surrounded Tilo’s mother, who, much like Ammu in The God of Small Things, had had an affair with an untouchable from the Paraya caste. Roy also borrows from life: Tilo’s mother, like Roy’s, is a single woman who started a school to support herself and her offspring.) The decades after college take Tilo’s three male friends—each is an admirer—along different routes. One is a higher-up in the intelligence bureaucracy, another is a journalist regarded as a national-security expert, and the third emerges as a leader of the Kashmiri underground. The recollections of Tilo’s encounters with the three men over the years are the novel’s most affecting feature: They are stories about desire and loss, but they also deliver a portrait of power as they document the criminal behavior of the cosmopolitan governing elites.

Since the publication of The God of Small Things, Roy has been a prolific and eloquent commentator on war, poverty, the flawed justice system in India, and the inequities of capitalism and rampant globalization. Ministry, too, takes up these political concerns. There are other continuities between her fiction and nonfiction, most notably her style. Take, for instance, a few lines from the new novel:

In every part of the legendary Valley of Kashmir, whatever people might be doing—walking, praying, bathing, cracking jokes, shelling walnuts, making love or taking a bus-ride home—they were in the rifle-sights of a soldier. And because they were in the rifle-sights of a soldier, whatever they might be doing—walking, praying, bathing, cracking jokes, shelling walnuts, making love or taking a bus-ride home—they were a legitimate target.

These sentences are unmistakably Roy’s, and could just as easily have existed in one of her nonfiction reports. They are marked by an eloquence even as they ambitiously string together various ideas and elements. Her prose is in this sense radically democratic (not unlike Jantar Mantar). And her unmistakable style and her way of seeing the world become something larger, too: a narrative glue holding together a novel that is made up of disjointed parts.

In the past, quite often, Roy has paid a price for her writing. In her essay “9 Is Not 11,” she reports on a popular TV anchor in India who demonized and heckled her and a human-rights lawyer on his show because they had questioned the integrity of the police and the armed forces. “Arundhati Roy and Prashant Bhushan, I hope you are watching this,” he said while addressing his viewers. “We think you are disgusting.” Roy held that such statements acted as incitement and threat. Soon, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness will reach this news anchor and others in India who want to dictate the republic’s history. I see a storm brewing.

Amitava Kumar’s novel Immigrant, Montana will be published in 2018 by Knopf.