“CAN I COME HOME WITH YOU?”

She’d approach you at Coney Island or Washington Square Park or on your way to work. “You look terrific,” she’d say—that was her phrase. You’d take her home; most people seemed to. You might take off your clothes, and sometimes she’d take off hers, too. She’d stalk off with her trophy: a photograph of you edged in darkness—as if seen through a keyhole—watching her warily. In the words of one biographer, you’d just been Arbused.

Almost from the beginning, Diane Arbus’s photographs were contentious for their blunt, some said cruel, depictions of her beloved “freaks”: twins, giants, dwarfs, drag queens. When she killed herself in 1971, the work became even more pathologized. She receives diagnoses in place of critical analyses. Her biographers handle her with tongs.

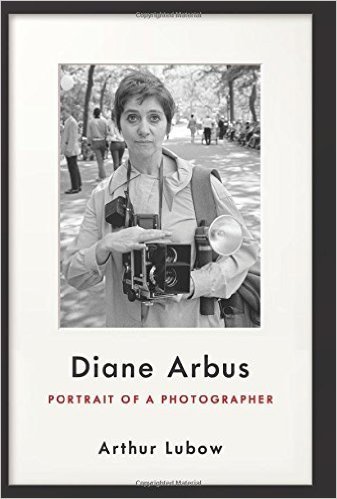

It’s not only her images and her lonely end that give people trouble. It’s what she prettily called her sexual adventures, which have come to light since her death in the accounts of her life by Patricia Bosworth, William Todd Schultz, and Arthur Lubow, whose Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer was published last year. Aside from photography, her adventures were her defining preoccupation. Sometimes they involved her subjects; she’d go home with people, shoot them, and sleep with them. Sometimes just strangers—a couple she followed to their Upper East Side apartment, a beautiful Puerto Rican boy she picked up on Third Avenue, a sailor sitting at the back of a Greyhound bus. Sometimes her adventures involved orgies. Sometimes, it’s said, her older brother.

Walker Evans called her a huntress—and she was as matter-of-fact about her predilections as her biographers are flustered. “She told me she’d never turned down any man who asked her to bed,” recalled one confidante at the time. “She’d say things like that as calmly as if she were reciting a recipe for biscuits.” Friends remembered her confessing compulsively or weeping while recounting these episodes. Others said she appeared dignified, coolly unafraid. They might all have been telling the truth. Her adventures were probably a combination of the desperate, dull, thrilling, numbing, humiliating—aren’t yours? But they’ve only ever been interpreted as tragic, as a symptom of depression and hideous loneliness, as proof that she was, in Schultz’s words, “a living suicide algorithm.”

Perhaps, perhaps not. Arbus was clear about what she wanted and why. The trouble is there’s still such scant understanding, let alone appreciation, for what it means to be a woman and wired the way she was.

We seem to know everything about the sexual preoccupations of great men. Of Kafka, Flaubert, Manto, Henry Miller, and V. S. Naipaul’s devotion to brothels (to name just the most ardent few); of Auden and Isherwood moving to Berlin “for the boys”; of Boswell’s almost majestic lifelong case of gonorrhea; of Gauguin in Tahiti; of Kehinde Wiley in Harlem, picking up men outside his studio to paint and sleep with. Whether you’re disapproving or admiring, it seems like an article of faith that for the male genius desire is a wellspring of creativity, intellectual inquiry, energy (well, perhaps less so for poor Boswell).

We have only the skimpiest vocabulary when it comes to writing about women in this way; about their sex lives as a grand adventure, as something that spurs on their work, something that belongs to them alone. We prefer their adventures to remain private, in the context of marriage—or at least love. Think of Nan Goldin’s photographs of her lovers Brian and Siobhan in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Sally Mann’s nudes of her husband in Proud Flesh. But Arbus was exceedingly strange and exceedingly free, intent on pursuing her attraction to seediness (you can smell the dank motel rooms in her photographs) and determined to face down her own disgust.

Sex became inextricable from her photography. Both took her deeper into people, into their mysteries, their secrets—and into herself, one imagines. “Diane told me she wanted to have sex with as many different kinds of people as possible because she was searching for an authenticity of experience—physical, emotional, psychological,” a friend said. “And the quickest, purest way to break through a person’s façade was through fucking.”

There is a tradition in queer women’s writing in which creative work, politics, and desire are comfortably intertwined. Consider Adrienne Rich, Minnie Bruce Pratt, and Audre Lorde, who wrote, in an essay on the political potential of the erotic: “There is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into sunlight against the body of a woman I love.” But Arbus was not looking for love. “Once she became an adventurer she went places no one else had ever gone to,” Arbus’s lover Marvin Israel said. “Those places were scary.” She wanted to cross all kinds of thresholds, emotional as well as physical. Some lovers chafed at what she wanted them to do to her—one told Patricia Bosworth, almost apologetically, that he just didn’t want to punch Arbus in the mouth. But there was nothing it seemed she wouldn’t do or couldn’t look at. For years a rumor circulated that she’d set up a camera to record her suicide, to shoot her as she lay, “crunched up” in her bathtub, in the medical examiner’s words, wrists sliced to the tendons. Fear was part of what Arbus was seeking, even if she didn’t understand entirely why. In therapy she discussed her habit of picking up odd-looking men on the street. For “experience,” her psychiatrist recalled, years later. “That’s all she could name it.”

And what did this experience yield? The goal of so much art, and especially photography, seems to be clarity, to bring things into the light. But not for Arbus, who was puzzled by porn’s literalness, and who once said, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know.” In her photos—of couples knotted up in bed or a stoop-shouldered elderly man huddling in the capable arms of a dominatrix—I see wonder where others have seen judgment. How strange we are, these photos suggest, what a great many things we’ve invented to do with our bodies. The “experience” she so doggedly pursued brought her, paradoxically, to a place of innocence, or at least awe: She restores the murk and mystery to sex; the child’s dread and fascination. Shortly before her death, in the last photography class she taught, she spoke of Brassaï, whose sooty photographs of Parisian prostitutes were a formative influence. “Lately it’s been striking me how I really love what I can’t see in a photograph . . . the element of actual physical darkness,” she said. “It’s very thrilling to see darkness again.”

Parul Sehgal is a columnist and senior editor at the New York Times Book Review.