A certain condition intuited by Franz Kafka, H. G. Adler lived—and lived to describe.

As if in a dream and for no rational reason, Hans Günther Adler (1910–1988), Kafka’s younger countryman and coreligionist, was transformed from a pedagogue into the powerless subject of an arbitrary regime under which untruth was ubiquitous and criminal behavior elevated to absolute law. One’s past and possessions were confiscated. Terror was the natural state. In that realm, Adler later wrote, “it was a fatal error to behave as if the world still was normal” rather than “a bottomless abyss of coercion” in which normality was a grotesque sham.

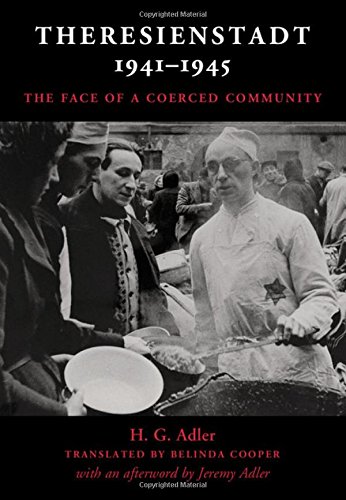

Adler’s Theresienstadt 1941–1945, completed in London and first published in German in 1955, is monograph as monument. A text of some six hundred pages, with another two hundred devoted to highly readable notes, sources, and appendices, it provides a detailed account of daily existence in the Nazi concentration camp Theresienstadt, known in Czech as Terezín. The “model” Nazi camp, created in an eighteenth-century garrison town thirty-nine miles from Prague, Theresienstadt was established in 1941 as a holding place for Jews, including those that the SS, which administered the camp, classified as “notables”—musicians, artists, scholars, decorated army officers, and Jewish community leaders of various political persuasions. Adler was himself held prisoner there for two years and eight months before being deported first to Auschwitz and then to a satellite camp of Buchenwald, from which he was liberated in April 1945—a progression he would describe with passionate opacity in his phantasmagoric novel The Journey (1962).

Adler’s portrait of what he called a “coerced community” is not easily classified. The Journey, belatedly published in English in 2008 and as Faulknerian as it is Kafkaesque, was deemed “Holocaust modernism” by its New York Times reviewer, Richard Lourie. Theresienstadt 1941–1945 is another sort of improbable modernism—a meticulous chronicle that is at once a sober and self-aware sociology of the absurd, a memoir in which the writer does not appear, and a penetrating ethnographic study. (Adler was influenced by anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski’s notion of the “participant-observer.”)

Theresienstadt 1941–1945 is sui generis, as is its subject. Precise yet metaphoric, dispassionate but anguished, Adler’s account of the Theresienstadt world, organized in chapters devoted to everything from housing and nutrition to legal conditions and cultural life, incorporates documents, oral testimony, and ultimately the author’s philosophy of history. Both a masterpiece of scholarship and a literary event, the book—which Adler began writing while a prisoner in Theresienstadt—is prefaced by the last lines of Kafka’s enigmatic story “A Country Doctor”: “Once one responds to a false alarm on the night bell, there’s no making it right—not ever.” Its final words are a cryptic warning from a doomed Theresienstadt inmate (who, although Adler does not say so, was the mother of his second wife): “One must be careful not to attach too much importance to oneself. All of us are more or less on the front lines.”

Some more than others. To oversee their prisoners, the SS appointed a “Jewish Elder,” a faux Führer who held the life of his Jewish subjects in his hands yet, as Adler points out, was “powerless against even the lowliest SS man.” The continual deportations to Auschwitz and other death camps in the east were ordered by the SS. The German forces stipulated the number and sometimes the ages of those to be deported, but for the most part the actual selection of deportees was made, under conditions of great secrecy, by the Elder, whose minions were also charged with the psychologically brutal implementation.

Thus the Elder presided over a bizarre social hierarchy: “Cliques, gossip, pleasure seeking, social events, and invitations to aesthetic and culinary enjoyments created a make-believe world. . . . People competed to be or become socially accepted, and a kind of royal household formed, complete with toadies.” Solidarity, which in some ways the camp fostered among the prisoners, was compromised: Adler writes that the Jewish administration could almost be compared to “the rationally incomprehensible authorities in Kafka’s novels” and notes that some did refer to their headquarters as “the Castle.” (Benjamin Murmelstein, the only Elder to survive the war, was the subject of Claude Lanzmann’s flawed but fascinating 2013 documentary, The Last of the Unjust.)

Between November 1941 and May 1945, approximately 154,000 Jews passed through Theresienstadt, which at times held six times as many inhabitants as the seven thousand the town was built to house. Approximately 33,000 died there, mainly from hunger and disease; another 88,000 were deported to extermination camps, including 84 percent of the ten thousand interned children. Largely uncomprehending, these young victims were forced, as Adler puts it, “to see their parents and all adults stripped of their rights” and thus become reduced themselves to children “who had to bow before an empty, meaningless discipline.”

Theresienstadt was a way station that was, essentially, the vestibule of Auschwitz. On one hand, transports of dazed Jewish families were shipped in from Western Europe. (“One witnessed the arrival of people whom one had known previously, and whose whole personality now seemed different and disturbed,” Adler writes.) On the other hand, trainloads of Jews disappeared into the east—although, according to Adler, Theresienstadt’s Jews remained unaware of the death camps until February 1943, and at that point only the Jewish leadership learned of their existence.

Noting that “during the departure of the transports, terrible incidents occurred, unique even in the history of the deportations, overabundant as they were in barbarity,” Adler describes a violence that was more than physical. Theresienstadt was founded on pretense. For one particular deportation, organized on the eve of Yom Kippur 1944, the then Elder, German Jewish functionary Paul Eppstein, was “shameless enough to send over a band to play dance music.” Two days later, Adler notes, “most of the deported had been gassed, and Eppstein had been shot.”

While the Lodz ghetto in Poland was organized as a slave-labor factory, the SS had little interest in exploiting Theresienstadt’s productive capability. The interned Jews were, in essence, their own product. In late 1943, the SS converted the camp into a showplace—no longer a ghetto but a “Jewish settlement area” to be toured by selected members of the German press and, later, representatives of the Danish Red Cross. During the camp’s so-called beautification, buildings were whitewashed, streets scrubbed, lawns laid, and roses planted. A pavilion was created for the camp’s children, who were permitted to use it for one day only: the day of the Red Cross’s visit.

“To create these paradisiacal conditions, 17,500 people first had to vanish into

Auschwitz,” Adler writes. “In the midst of the insanity of beautification,” another 7,500—many of whom, “in tragic hope,” had devoted their energy to the campaign—were deported. The beautification was consecrated by a Nazi pseudo-documentary directed, under Murmelstein’s supervision, by Kurt Gerron, a prominent German Jewish actor who, along with the performing artists featured in the film, was subsequently shipped to Auschwitz in the massive transports of late 1944 that included Adler, his first wife, and her mother. (Gertrud Adler, a medical doctor, appears to have been a saint who chose to go to the gas chamber so that her mother would not die alone.)

In any case, the beautification program worked—the Red Cross filed a favorable report. Compared to the rest of wartime Europe, Theresienstadt seemed practically like a spa, which it was . . . for the SS, who were waited on by Jewish slaves in the luxury hostel that served as a residence for the camp commandant and his staff. It was the pretext of normality, however debased, and the denial of mass murder, even as thousands of inmates were selected and sent to their doom, that accounts for what Adler calls Theresienstadt’s uniquely “uncanny” quality. The death factory that was Auschwitz was far more terrible, but there the slaughter was undisguised—there was no possibility for self-deception. Theresienstadt, by contrast, was a “ghastly carnival of which almost no one was entirely conscious.” Like ghosts, the prisoners “lived on the edge between Something and Nothing.”

Half-starved, ridden with disease, plagued by vermin, surrounded by garbage, subject to rumors, and numbed by denial, the Jews of Theresienstadt existed in a state of constant apprehension. “It is no exaggeration to assume that a majority of the prisoners were afflicted with neuropathic or psychopathic alterations,” Adler writes. “The dynamic of all known human passions—strangely transformed, exaggerated, and shrill—played itself out in this demonic twilight zone.”

In his concluding section, titled “The Psychological Face of the Coerced Community,” Adler undertakes a theorization of what he calls a “gruesome ghost dance.” Looking for the meaning of their fate, many Jews blamed themselves or believed they were “the objects of a monstrous experiment.” Adler refuses to dignify the notion of a Nazi experiment. Theresienstadt, he argues, was made possible by several factors, including the twentieth-century tendency toward dehumanization, the corresponding elevation of a Führer principle, the inability of the Occidental mind to synthesize idealism and materialism so that “everything organic was mechanized to a previously unheard-of degree,” and the demonization of Europe’s Jews. His thinking resembles that of Hannah Arendt in The Origins of Totalitarianism, although she is far more historically minded in her discussions of anti-Semitism, the doctrine of racial superiority, and imperialism.

But then, unlike Arendt, Adler wrote from firsthand experience. His observations and his microtheorizing—as applied to the specifics, for example, of “legal conditions” in the camp—are more powerful than his notion of “mechanical materialism.” Theresienstadt, where “every improvement in the difficult living conditions at the same time contributed to the prisoners’ deception and self-deception,” obliterated Adler’s world even as it made him a writer.

Religious life played a relatively minor role in Theresienstadt, but intellectual and even artistic pursuits were possible—including detailed documentary paintings and drawings made in secret. Writing in 1999, Milan Kundera called the culture of Theresienstadt’s prisoners “incomparably more important than the macabre theatre of their jailers,” but, in fact, the two were related. Thanks to the looting of Jewish institutions, Theresienstadt had perhaps the most extensive Hebrew library in Europe; it also had a significant population of academics.

It is terrifying to regard Theresienstadt as a twentieth-century European university devoted to twentieth-century European studies, but in a sense it was. Adler lists frequent lectures, on subjects ranging from the chemistry of food to Beethoven’s sonatas to “Taxes and the Science of Finance.” Perhaps these should be considered contributions to what, in analyzing the “situation of the writer in 1947,” Jean-Paul Sartre called the “literature of extreme situations.”

Adler cites a sixtieth-birthday memorial for Franz Kafka held at the camp and attended by the writer’s youngest sister, Ottilie. He elsewhere records that Ottilie was later deported to Auschwitz, but never mentions that it was he who organized the celebration.

J. Hoberman is the author of many books on film, including An Army of Phantoms: American Movies and the Making of the Cold War (The New Press, 2011).