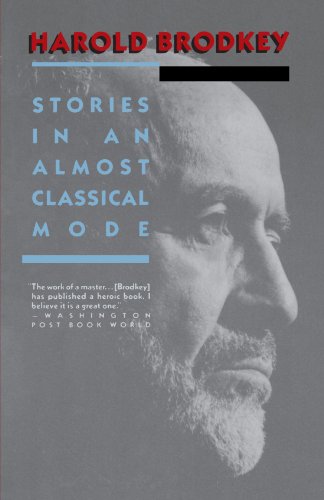

IS HAROLD BRODKEY THE GREATEST—or at any rate, the most lauded—writer who never produced a great book? His 1958 debut, First Love and Other Sorrows, was a big hit but hasn’t aged well. Sure, “The State of Grace,” the title story, and “The Quarrel” form a brilliant little trilogy, sharing a narrator and depicting a midcentury adolescence made numinous by yearning—economic, intellectual, cultural, erotic; take your pick if you can tell them apart. A male classmate in “First Love . . .” looks “like a statue that had been rubbed with honey and warm wax, to get a golden tone, and he carried at all times, in the neatness of his features and the secret proportions of his face and body that made him so handsome in that particular way, the threat of seduction.” But the other six stories offer diminishing returns, and Brodkey spent the next thirty years bluffing about an epic novel that kept failing to materialize save in sporadic fragments appearing in the New Yorker and other magazines. In 1988 he published his second book, a six-hundred-page collection of those fragments that somehow was not the promised novel, but rather Stories in an Almost Classical Mode. (The novel finally appeared in 1991, and made an 835-page flop, but that’s a story in an almost classical mode for another day.)

There are eighteen stories in Stories, several of them novella-length, not all of them gems. Gordon Lish, its editor, once sat me down—this was back when he still liked me, circa 2007—and named the seven stories he regarded as essential, and told me to discard the rest. His picks were “Innocence,” “His Son, in His Arms, in Light, Aloft,” “Largely an Oral History of My Mother,” “Verona: A Young Woman Speaks,” “Ceil,” “S.L.,” and “The Boys on Their Bikes.” My judgments don’t match his exactly, but the proportion (38 percent of the book) seems about right.

“Verona” is narrated by a teenager recalling a European tour with her family: “I feel joy or amusement or I don’t know what; it is all through me, like a nausea—I am ready to scream and laugh, that laughter that comes out like magical, drunken, awful, and yet pure spit or vomit or God knows what, makes me a child mad with laughter.” In “Play” a boy feels sexual friction while wrestling with a younger playmate; he does not understand what is occurring but his instinct is to feed the sensation. As discovery becomes knowledge, serendipity becomes intent, and the kinky innocence shades into menace.

Something similar is at work in “Innocence,” Brodkey’s most notorious story, in which a Harvard undergraduate named Wiley tricks his sexually self-effacing girlfriend, Orra (yes, really, he named her that), into having her first orgasm. It is a thirty-page story with a twenty-page sex scene, most of which consists of Wiley’s inner monologue while performing cunnilingus, which he has told Orra is for his own pleasure, because she gets upset whenever he pays attention to her needs. “The darkness of my senses when the rhythm absorbed me (so that I vanished from my awareness, so that I was blotted up and was a stain, a squid hidden, stroking Orra) made it twilight or night for me; and my listening for her pleasure, for our track on that markless ocean, gave me the sense that where we were. . .” Actually I’m going to go ahead and stop right there.

Two obvious comments. First, that what is great about Brodkey is inextricable from what is awful about him. Second, that this story is an enormous joke that nonetheless begs to be taken seriously, which come to think of it describes undergraduate men across the generations. When I was nineteen, “Innocence” blew my mind. Who knew that you could write about sex (and/or perform cunnilingus) with such nuance—and for so long? These days the main thing that stands out to me is Wiley’s fickle sense of when “no” does and doesn’t mean “no.” It’s a bit, as the kids say, problematic. But if “Innocence” has outlived its status as the literature of sexual liberation, it survives (or deserves to survive) as the literature of radical candor. Which feels true of Brodkey in general. Nothing is unsayable for him and all of it is said more or less gorgeously. The only catch is that a lot of it is repetitive, egotistical, shellacked in misogyny, and boring as hell. Perhaps the highest irony is that this maximalist’s maximalist is best appreciated in small doses. A mouthful or two will usually get you there, should you happen to find yourself in the mood.

Justin Taylor is the author of the story collection Flings (Harper, 2014).