In September of last year, two months before the presidential election, then-candidate Donald Trump appeared on NBC’s Tonight Show. In what felt like one of the grossest media moments of our recent era—and let’s face it, the competition is stiff—host Jimmy Fallon asked his guest whether it would be OK to do something “not presidential” with him. “Can I mess your hair up?” Fallon proposed, puppyish and wide-eyed. Trump, pantomiming good-natured reluctance, let the host reach over and muss his thin, gingery strands, setting that precarious hair soufflé askew and earning a big hand from the audience. “Donald Trump, everybody!” Fallon shouted, in tones of elation. Afterward, having been roundly criticized for treating Trump as a benign, nay, adorable, mascot rather than a nonpareil lying, racist politician, Fallon was defensive. “Have you seen my show?” he asked. “I’m never too hard on anyone.”

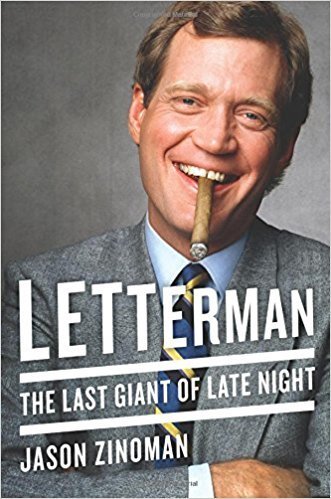

He was right, of course, and not just about his own show. That willingness to please—and refusal to offend or test—has over the past half century largely characterized US talk shows, which tend to favor a smooth blend of entertainment and business that goes down easy. Most often, the task for mainstream hosts is to cozily promote their guests’ forthcoming projects—up to and including the presidency. On a show like that, any snag of tension can feel like a revelation. In his lovingly detailed, deeply researched biography Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night (Harper, $29), Jason Zinoman describes how his subject became a seminal provider of such tension, in part by embodying it. The Letterman Zinoman portrays is a tortured, conflicted figure, eager to follow in the footsteps of his hero, longtime Tonight Show host Johnny Carson, and lead the biggest, most popular talk show on earth, but at the same time egged on by his more daring collaborators—chiefly the brilliant Merrill Markoe, his onetime romantic partner and the first head writer of Late Night with David Letterman—to seek out the true comedy weirdness that more closely matched his own spiky and self-lacerating nature.

In Zinoman’s description, Letterman was more an ironist than a radical, and his insurrection was carried out more often on the level of tone than that of substance. Still, his relentless urge to defy the expectations of both guests and audience, especially in his first decade in late night, proved an unusual and amazingly creative force within the soft-centered world he inhabited. The fact that later on, after he moved in 1993 from NBC’s Late Night to the much bigger Late Show on CBS, his style became increasingly calcified and predictable, sometimes even pandering, speaks to the ultimate limitations of a subversive impulse within any truly popular context.

Zinoman, however, really gives us a renewed sense of Letterman’s more interesting, sexier period—the years in which young Dave worked up to and then hosted Late Night. Following a lower-middle-class, if white-bread, upbringing in Indiana, Letterman went into local radio and television, then moved to Los Angeles to do stand-up. A big break came when he was booked on the Carson show, where, in his first appearance of many, he got big laughs by calling out the sign forbidding the placing of glass and metal objects in airplane toilets (“I like to go back there, wash a load of dishes”). It was a tactic that would later become a Letterman-show mainstay—making strange the unremarkable surfaces of everyday life. His popularity on Carson, where he soon began to guest-host, landed him a short-lived morning show, and then, finally, his own late-night slot.

Throughout these years, his chief strength was the signature stance of winking irony with which he masked both an intense self-loathing and a fervent will to power. (Markoe bore the brunt of those tendencies: Faced with Letterman’s constant bitching that the show was laugh-free and its ratings never high enough, she once cracked to the other writers, “You sleep with him.”) Letterman’s persona revealed little of this anguish. As Zinoman puts it, “His smirking tone was so consistently knowing that he seemed as if he must know something.” This was an attitude fit for the cynical mood of the 1980s, and Zinoman emphasizes Letterman’s significance as an avatar of cool noncommitment, a figure of his time. In that, Letterman resembled that other pop-cultural phenomenon of the era, Jim Davis’s Garfield—the rotund cartoon feline also riven by self-doubt and haunted by grandiose fantasies of domination while projecting an aloofness that often verged on the cruel. “Letterman told you nothing about himself, and he mocked anyone who did,” Zinoman writes, essentially summing up every guy I had a crush on between the ages of twelve and twenty-two.

The book also makes clear, though, why what could easily have turned into an arid exercise in knee-jerk assholism didn’t. Part of what made the show work was the friction that arose between Letterman and his guests, which often made for incredible TV. Audiences were refreshed by Letterman’s sometimes overt hostility toward celebrities, which came naturally to him, since he had a “sensitive ear for phoniness and canned talking points.” Letterman generated other kinds of tension, too. Throughout the ’80s, the comedian Sandra Bernhard repeatedly appeared on the show in the role of a half-desperate, half-domineering seductress, aggressively coming on to the straitlaced Letterman. (In one bit, claiming she was “destroyed” by her desire for him, she brought along a series of self-help books of the Women Who Love Too Much variety, finally arriving at the punch line: gifting Letterman the book When Smart People Fail.) If observing the current choreographed celebrity-host interactions à la Fallon is like spying on joyless, going-through-the-motions intercourse, watching clips of the unpredictable Bernhard-Letterman exchanges from the ’80s feels more like accidentally intruding on that tense, subtly antagonistic moment when two really smart, really hot people are on the verge of either fighting or fucking.

Yet the real key to Letterman’s success was his collaboration with and reliance on Late Night’s creative team, most importantly Markoe, who left her position as head writer at the end of the show’s first year but continued to be substantially involved until 1988. It was Markoe who established the show’s sharply conceptual oddball sensibility, pushing Letterman toward a dadaesque approach wherein anything “stupid”—i.e., nonsensically bizarre—was good. Many of the early-period Letterman bits relied on upending what a viewer might expect from a show and, as much as possible, ramming the weirdness of real life into the made-up TV world. Stupid Pet Tricks, a brainchild of Markoe’s and essentially a collection of protomemes, was a case in point: “We have this multimillion-dollar operation and we’re showing a dog closing a door,” one of the show’s writers said to Zinoman. Markoe also invented the long-running Viewer Mail, a parody of a similar mail-answering segment on 60 Minutes (Markoe: “I thought it would be funny to just present our viewers: irrational, insane, illiterate”). And the writer George Meyer came up with a verging-on-surreal running gag in which an enormous doorknob kept popping up apropos of nothing in various sketches, with Letterman repeatedly and solemnly emphasizing how large it was.

Markoe, the behind-the-scenes Jewish woman to Letterman’s clean-cut, Waspy leading man, is, Zinoman suggests, a central but often overlooked piece of the puzzle of Letterman’s rise in sexist, racist Hollywood. After all, in 1979 Carson told Rolling Stone that women comics were “a little aggressive for my taste”; and Zinoman cites Albert Brooks, who asked, “Why are no talk-show hosts Jewish? . . . Because no one wants to go to bed with a Jew?” (Needless to say, racial, ethnic, and gender diversity has barely improved in talk shows today.) Zinoman also quotes key passages from the diaries Markoe kept during her Late Night years, and they’re a delight for their reflective, self-questioning quality—so different from Letterman’s detachment, which grew increasingly forbidding as the show became more and more successful. Her quotes provide some of the best laughs in a book that’s ultimately pretty serious. When she discovers that Letterman, who’d been muttering darkly about his health, has in fact been cheating on her, she tells him, “Look, you are either dying or you are dating. But you can’t be both.”

Letterman’s later years come across in the book pretty much as they too often did on television—as a bit of a bummer. By then a huge star, he was guarded by multiple producers who kept the world at bay. The writing staff were among those excluded, which all but killed off the show’s experimentalism. Anyone who’s worked in a dysfunctional office will feel a shiver of recognition at Zinoman’s descriptions of palace intrigues (which younger staffers was Dave sleeping with?) and byzantine, tailored-to-the-boss practices (including

Letterman’s maddeningly inconvenient reliance on a typewriter to prepare jokes preshow). It didn’t help that, after moving to the Late Show, where he stayed until his retirement in 2015, Letterman had to adjust his material to a much larger theater and enormous home-viewing audience, so that a more mainstream spirit pervaded the operation. The characteristically absurdist critique of show-business conventions was gradually abandoned. And while Letterman didn’t become a Mr. Nice, like his Tonight Show nemesis Jay Leno, his ornery, cantankerous affect grew broader, becoming more of a tic than a meaningful comedic sensibility. The show was no longer “stupid,” but it was occasionally “dumb”: Letterman often relied on a lowest-common-denominator Joe Lunchpail routine (this was around the time, Zinoman writes, that the host became enamored of MTV’s Beavis and Butt-Head), or on the character of a horny old creep, leering at starlets. There was also his lapse, for a time, into a strained earnestness, like the painful moment in 2009 when, following a blackmail attempt by the boyfriend of a Late Show employee Letterman was having an affair with, the married host had to confess his sins on air.

Letterman wasn’t exactly the diametric opposite of a suck-up like Fallon; he was more a strange amalgam of renegade and crowd-pleaser. That complexity, however, was what was most intriguing about him—why you couldn’t look away, and why his legacy of pleasurable unease still fascinates. As Cher told him in a revealing interview all the way back in 1986, and as Zinoman’s book bears out, “They’re not mutually exclusive, being interesting and being an asshole.”

Naomi Fry is a writer living in Brooklyn.