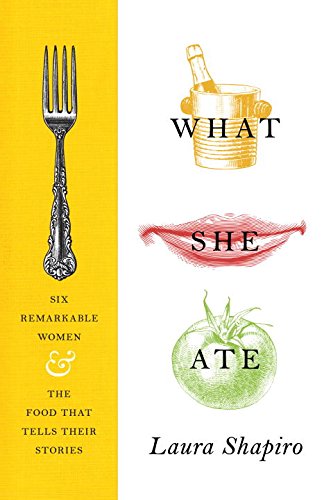

Protein powder stirred into diet orange soda. Milk pudding with a touch of voodoo mixed in. Thick hunks of gingerbread, boiled bacon with broad beans, “Shrimp Wiggle,” and oceans of champagne. These are just some examples of the food and drink that pop up in Laura Shapiro’s new book, What She Ate: Six Remarkable Women and the Food That Tells Their Stories (Viking, $27). As you might guess, the collection of women responsible for this cornucopia is, to put it mildly, eclectic. This volume is bookended by Dorothy Wordsworth (William’s sister—he was the gingerbread fan) and Helen Gurley Brown, of Cosmopolitan and Sex and the Single Girl fame (who else could invent that synthetic diet protein drink?). Between them—as the book moves chronologically through each woman’s story, from 1771 to 2012—come Rosa Lewis, an Edwardian-era caterer and hotel owner; Eleanor Roosevelt; Eva Braun; and the British novelist Barbara Pym.

What on earth is this crowd of women doing hanging around with one another? Just imagine the cocktail-party chat. Eleanor Roosevelt to Eva Braun: “You’re the führer’s mistress? I’m the first lady.” Barbara Pym to Helen Gurley Brown: “I write domestic novels about ordinary women. What do you do?” Rosa Lewis to Dorothy Wordsworth: “You may be feeding one of our country’s greatest poets, but King Edward loves my cooking.” It’s a strain to see why they’re all here together, until, suddenly, it isn’t.

Shapiro is the author of two previous books about women and food, Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century (1986) and Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America (2004), both of which are entertaining and deeply insightful about what women’s relationships with food say about a given culture at a particular moment. If anyone knows how to gather a group of women together, it’s her. That she’s selected her subjects this time not from a specific era but according to her own interests is a gamble, but her nose for a good story doesn’t fail her. It turns out that these women have more in common than you might imagine. They’re linked, like women everywhere, by the covert methods they used to acquire whatever power was available to them. At a moment when women have far more overt ways of expressing their desire for influence—if not fully exerting it—it’s instructive to see the gains Shapiro’s heroines made via more subterranean methods. Each one, in her own way, used food as both “her shield and her weapon.”

Brown and Braun are the abstainers of the bunch (though Shapiro acknowledges “the moral distance that separates [Braun] from everyone else in this collection”). They turned denial of their appetites (alimentary, not carnal) into a form of leverage and a marker of self-worth. The end to Braun’s means was purely personal. Because she was Hitler’s secret paramour, hidden from the public to preserve his image as a leader loyal to his country first and foremost, the one place she held court was at table, during the lavish meals held for party higher-ups in the famous bunker and elsewhere as Europe was being ravaged. She was there to be seen by Hitler’s co-conspirators and acolytes, and her desire for attention was greater than any of her other needs. “The woman who starred in her daydreams as leading lady of the Reich was always picture-perfect. . . . [S]he was always fixated on her figure,” Shapiro writes. In a life filled with Nazi plunder—Hitler sent her a special stash of Ukrainian bacon when that country was invaded in 1942—she ate very little, electing instead to drink as much champagne as possible to simultaneously keep her svelte physique and remain the life of the party. Hitler was the only thing she cared about, and she lived almost solely for her usefulness to him.

Brown, meanwhile, not only worked out a disordered eating plan for herself but broadcast it to the millions of women influenced by the magazine she edited and the books she wrote. “For Helen,” Shapiro writes, “dieting was a mission that went well beyond weight loss. It was a crusade against every enemy she had ever imagined lurking in her future, from poverty to spinsterhood to a pitiable old age.” When Gloria Steinem asked Brown to say “something strong and positive about herself—not coy, not flirtatious, but something that reflected the serious, complicated person who was in there,” as Shapiro recounts, Brown came up with: “I’m skinny! I’m skinny!”

Women, of course, have always been expected to make sacrifices. In the early nineteenth century, Dorothy Wordsworth was devoted first to her dreamy brother’s housekeeping needs and then, after he married, to his son’s. Soon after her nephew no longer needed her, she succumbed to a bout of intestinal illness from which she never fully recovered (the treatment, laudanum, was almost as damaging as the illness itself). Released from constant concern for the needs of others, she spent the last phase of her life descending into dementia and demanding, at last—after a life of caretaking—to be fed herself. “She wanted to eat, she demanded to eat; her pleas became incessant. For the first time in her life she grew fat, then very fat,” Shapiro tells us. William was made frantic by her requests for an endless stream of rich foods—she at last had his full attention.

Society’s unwillingness to acknowledge women’s true selves and needs was territory Barbara Pym quietly remade over the course of her many novels (which I cannot recommend highly enough). Taken collectively, the characters she writes about are an argument for the importance and nuance of everyday women’s lives, with an emphasis on food. Like most of us, her characters are well acquainted with the truth that sometimes all you have in the fridge is wilted lettuce and a cheese rind, and so you make a lonely salad out of that. Other times, you get to go out to a posh restaurant, but even that might not quite live up to your dreams. (Taken out for lunch at one such place by her publisher, Pym looked around with her usual keen eye and saw that “all the other diners in the room seemed to be men.”) She created a permanent place for these women—real women—in literature, almost without anyone’s realizing it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was almost lost to us. After she published six novels in thirteen years, her publishing house’s new editorial director, Tom Maschler, axed her for the likes of Thomas Pynchon, Joseph Heller, and Ian Fleming. She, as well as all her “excellent women” (as she titled one book), remained on hiatus for fourteen long years, but she continued to write, believing in the need for her kind of women in books. In 1977, she was vindicated. The Times Literary Supplement ran a list of the most underrated writers of the past seventy-five years, and Pym was the only living writer nominated twice. Suddenly, she was back in fashion, and Tom Maschler began asking about her backlist and a manuscript he had rejected. She had already signed with another publisher, and she and her sister celebrated Maschler’s loss with a bit of vindictive, anthropomorphizing cooking. “Hilary and I invented a Maschler pudding,” Pym wrote to her longtime friend Philip Larkin, calling it “a kind of milk jelly.”

Pym is far from the only woman here whose story features the poor choices of men. We’ve long known that FDR had affairs. What we—or at least I—didn’t know was that Eleanor got her payback, in part, through the White House kitchen. She chose one Henrietta Nesbitt, “the most reviled cook in presidential history,” as the housekeeper in charge of menu planning. “Taste, texture, serving the food at the proper temperature, making sure each dish looked appetizing—these were niceties that did not concern the housekeeper,” Shapiro writes. In 1937, Ernest Hemingway described a meal he’d eaten as a White House guest: “We had rain-water soup followed by rubber squab, a nice wilted salad and a cake some admirer had sent in. An enthusiastic but unskilled admirer.” As the Roosevelts’ marriage ran on parallel tracks, Eleanor chose to ignore FDR’s infidelities. But, as Shapiro notes, “three times a day the First Lady made sure that her husband received a large helping of pent-up anger.” One Roosevelt scholar called Mrs. Nesbitt “ER’s Revenge.”

The combatants in the Roosevelts’ culinary battle were born into the highest levels of society, but Shapiro also tells the story of Rosa Lewis, who used food as a mechanism to game the seemingly impregnable British class system, rising from Cockney maid to trusted Buckingham Palace caterer. She eventually grew successful enough to purchase a hotel, where the kitchen staff was entirely female because, as she told a reporter, “A good woman cook is better than a man any time.” As Shapiro writes, “When Rosa chose high-class cookery as her future, she was gaining access not only to a cuisine, but to all the social behaviors associated with it. She was learning the secret handshake.”

The Prince of Wales, who became Edward VII in 1901, was her muse. He liked his truffles whole, but his favorite dish, as Lewis knew before anyone else, was the very humble broad beans and bacon. “Rosa understood his hunger,” Shapiro tells us. Talk about power.

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).