Love meant to take refuge from one’s own world in another’s . . .

—Hermann Broch

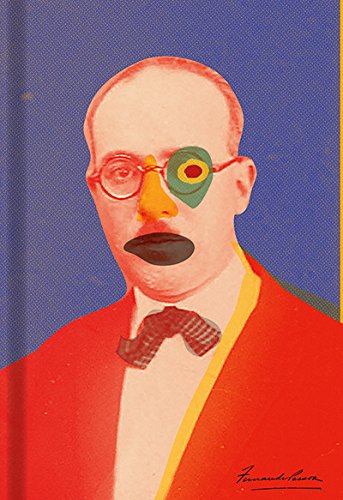

The Portuguese poet and essayist Fernando Pessoa aspired to be unlike himself. Over the course of his life as a commercial and literary translator in fin de siècle Lisbon, he assumed around 130 “heteronyms,” invented identities with distinctive histories. These personalities came to subsume his own quiet biography: In a letter to the writer Adolfo Casais Monteiro, he wrote, “I, who created them all, was the one who was least there.” Instead of there, he was elsewhere, and instead of himself, a celibate autodidact and recluse, he was variously Ricardo Reis, a doctor from Porto; Alberto Caeiro, an orphan; and Álvaro de Campos, a naval engineer trained in Scotland. Most famously, he was Bernardo Soares, his “semi-heteronym” and most intimate alter ego, the assistant bookkeeper for a textile company in Lisbon and the primary narrator of the beloved Book of Disquiet.

Like its author, The Book of Disquiet diverges from itself. Assembled by scholars and editors from the frenzy of papers that Pessoa left scattered in his trunks when he died, the book has no official text, and no two versions are exactly alike. Selections that feature in some editions are absent from others, and even the elements common to all its variants are presented in different orders. The latest iteration of the classic, translated by Margaret Jull Costa, is more comprehensive than the rest: It is exhaustive and organized chronologically, and it includes a section that is usually excised. The first one-hundred and sixty pages, written from 1913 through 1920, are presented as the work of another heteronym, Vicente Guedes, a cranky Symbolist poet and aesthete. The second two-hundred and eighty, composed between 1929 and 1934, return to the familiar figure of the bedraggled Bernardo Soares, whose vivid dream life runs parallel to his dreary office job.

It turns out that chronology cannot impose linearity on the wayward Book of Disquiet. Even in its most coherent form to date, it is a fragmented, diaristic clutter of musings on the nature of reality, illusion, and art. The only piece of plotting anywhere in the four-hundred-plus-page work is the frame story in its short preface, in which a third, unnamed narrator encounters Guedes in a cheap restaurant. The character strikes up a casual friendship with the poet and promises to publish his writings someday. Aside from these introductory pages of almost-action, The Book of Disquiet is an inventory of inertia, a litany of rainy days, insomnias, colds, and discomforts. Reading it is like turning over and over, trying and failing to sleep. The closest thing to an event is an unexpected thunderstorm some two hundred pages in.

Of course, there are plenty of books that give the impression of eventfulness without chronicling all that many events: Oblomov lies in bed for most of his eponymous novel, and Mrs. Dalloway plans a party for much of hers. If there is a soggier sense in which nothing happens in The Book of Disquiet, it’s because an occurrence can prove interesting or eventful only insofar as it carries some weight. Pessoa’s narrators have no capacity for investment, so nothing they witness strikes them as eventful. “Things . . . pass but never happen”: Life flits but fails to sink in. Soares describes himself as the “indifferent narrator of my autobiography without events, of my history without a life.”

Events glance off Pessoa’s narrators until they’re nonevents, but selfhood clings until it mires. The self is luggage we are doomed to lug everywhere, a ubiquitous location that admits of no escape. Soares’s prose is clotted with the lugubrious imagery of heaviness, of dragging: “With an enormous effort I rise from my seat only to find that I still seem to be carrying it around with me.” On the few occasions when he ventures out of Lisbon, he discovers that travel is futile: Attempts at departure only return us to the homes we’d hoped to leave. “Someone who has sailed every sea has merely sailed through the monotony of himself,” he concludes. No matter where we go, “we can never disembark from ourselves.” “Landscapes are repetitions” because they are projections that issue from the same unendurable source. Surveying his surroundings, Soares laments, “What is there in all this but myself? Ah, but in that and only that lies tedium.”

True movement, real travel, would require us to shed ourselves. A different life is the only destination worth the voyage. As Guedes reflects, “I envy in everyone the fact that they are not me. Of all impossibilities, and this always seemed to me the greatest, this was the one that made up the greater part of my daily dose of anguish.” He would prefer even a prosaic occupation to the deadening proximities of his own: “How often it pains me not to be the captain of that ship, the driver of that train! To be some other banal individual whose life, because not mine, fills me with delicious longing and a poetic sense of otherness!”

But to become someone else, Pessoa admits, is to replicate the problem of monotony. To adopt another self is to enter into a new hell of routines and habits, to submit to a different but equally crushing burden of sorrow and sameness. The only real reprieve from the blistering friction of your one tired life is to be both the same and different at once. We want only what we don’t have, and a perspective is novel only so long as it’s somebody else’s. To enjoy a foray into a new experience, to become a true tourist there, you have to remain yourself while becoming someone else: “The insatiable, innumerable longing,” writes Guedes, is “to be always the same and always other.”

Seventy pages later, Guedes concludes that this is the sentiment that undergirds

our passions: We love others because we are sick of ourselves. To love is to want to be together, but to do so alone. It requires the distance of difference—we can’t derive satisfaction or excitement from the familiarity of ourselves—but it also seeks to collapse the rift that keeps a lover distinct and apart from the object of her affection. Love is a mood that thereby undoes itself, negating its practitioners:

Love requires us to be both identical and different, which isn’t possible in logic, still less in life. Love wants to possess, to make its own something that must remain outside in order for it to be able to distinguish between the something it has made its own and its own self. To love is to surrender oneself. The greater the surrender, the greater the love. However, to surrender completely is to surrender one’s consciousness to the other person. The greatest love, therefore, is death or oblivion or renunciation—all loves are the abomination of love.

Like tedium, love poses an insuperable paradox, requiring us to be what we are not without ceasing to be what we are. Guedes concludes that it “is a mysticism that wants to be put into practice, an impossibility that according to our dreams should be possible.”

Fiction is the province of impossibility, and at its best it empowers us to plumb other lives even as we inhabit our own.

Pessoa is right that love requires self-exile, but he has no facility for the foreign territories of character, and neither Guedes nor Soares manages much in the way of escape. Both narrators remain agonizingly inward-looking, and for all their quibbles over minor matters of aesthetic doctrine, they sound essentially the same. “While I can sense the movement of people with my eyes, I am too steeped in my own thoughts to actually see them,” confesses Soares.

Pessoa suffers from the same malady: His selfhood is incurable. He commands a cult following as a poet because his language is disconsolately beautiful, and The Book of Disquiet is exquisite. Nobody can render the hollowed horror of a world wrung out quite as gorgeously as Pessoa, whose “whole body was a suppressed scream,” who had “indigestion of the soul,” who was “a shelf full of empty bottles,” a fugitive from his own life. But Pessoa’s best lines are evocations of precisely the crabbed loneliness that he writes to outrun, and many of his best-known poems are hymns to this same sense of entrapment and unchangeability. Pessoa’s heteronymous inventions only iterate and reiterate their creator’s malaise. Even they seem to recognize that all their poems express the same sentiment. Alberto Caeiro writes, “Each poem of mine explains it, / Though all my poems are different, / Because each thing that exists is always proclaiming it.” Ricardo Reis concurs: “The whole moon, because it rides so high,” he muses, “is reflected in each pool.” No matter the medium, we’re stuck with the same old message. Why bother with heteronyms that all sound alike?

For all its lyricism, The Book of Disquiet is for the most part sullen, painful to read. It takes on the repetitive cadence of ineluctable boredom, relentless as a fly that’s shooed away over and over again. It circles back repeatedly to the same ideas: that art is preferable to life; that action is a betrayal of the perfection of imaginings; that we should sleep as often as we can; that we are sometimes assailed by small moments of hope or protohappiness occasioned by changes in the weather or surprises on the street, a bracingly yellow banana or a swatch of sudden sunshine; but that no matter what we do, things continue, ultimately, in the same unbearable vein. The unfinished Book of Disquietmay be multiple, but it is singularly solipsistic.

Becca Rothfeld lives and reads in Somerville, MA.